From the archives: Originally posted on March 24, 2010. Happy Passover, all!

In the late 19th century, my great-grandfather Emanuel Michael Rosenfelder left Bavaria and became a circuit-riding rabbi, serving Jewish traders and merchants along the Mississippi River, in Natchez, Baton Rouge, and New Orleans. When he registered to vote in 1876 in Ouachita Parish, Louisiana, the clerk, obviously unfamiliar with Jewish theology, recorded Rabbi Rosenfelder’s profession as “Minister of the Gospel.” In New Orleans, he met and married my great-grandmother, a teenager who had been living in a Jewish orphanage after her parents died in a Yellow Fever epidemic. Fleeing the threat of tropical illness, the Rosenfelders journeyed north up the river and settled in Louisville, Kentucky. My grandmother was born and raised there, one of eight children, and they gave her a Southern francophone name, Aimee Helen.

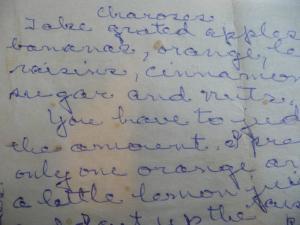

In preparing for the Passover Seder next week, I turned to Grandma’s charoset recipe, written out for me in her shaky handwriting on a translucent scrap of onion-skin paper. The typical Ashkenazic (European Jewish) recipe for charoset is a mix of chopped apples, almonds, cinnamon and sweet kosher wine, and in many families, the big debate is whether to include raisins. Meanwhile, the Sephardim (Jews from Spain, Portugal and the Middle East) make charoset with desert fruits including dates, figs, pistachios and pine nuts. Charoset, served on matzah as part of the ritual Passover meal, is meant to represent either the mortar used by Jewish slaves when building the pyramids, or the sensual foods mentioned in the Song of Songs.

But Aimee Helen Rosenfelder Katz’s charoset reflects the sojourn of her family in the Deep South, surprising us with oranges, bananas and pecans. I grew up on this charoset at Passover each year, and I love the tart sparkle of the oranges, the smoothness of the bananas, the sweet pecans. She was a bit of a southern belle, my Jewish grandma, with very proper manners, and a private girls’ school education. But she was also an intellectual role model, with a French degree from the University of Louisville, and graduate studies at Barnard. During Word War I, she taught French to American soldiers heading off to fight in Europe.

Someday, her first great-grandchild, my daughter Aimee Helen, will inherit the charoset recipe, a tangible reminder of the uniquely American story of her Jewish ancestors. At the Passover Seder, we are commanded to explain the religious significance of each of the seemingly incongruous objects arranged around the Seder plate: the egg, the roasted shank bone, the parsley, the horseradish… In the same way, I feel commanded to explain to my children the significance of each disparate family tradition, each story, each character on the colorful plate representing their heritage. Given the complexity and depth and resonance of the stories from our Jewish family, I cannot imagine raising my children solely as Christians. But neither can I imagine ignoring everything else on their family plate.

Aimee Helen’s Southern-Style Charoset

3 peeled and grated apples

2 peeled and grated oranges

2 chopped bananas

1 squeezed half-lemon

1 cup chopped toasted pecans

½ cup chopped raisins (optional)

½ tsp cinnamon

1 tbs sweet kosher wine

Sugar to taste

Mix all ingredients and give it some time for the flavors to mix and deepen. It only gets better the next day. Aimee Helen noted, “I prefer pecans, but almonds if you prefer.”

Susan Katz Miller’s book, Being Both: Embracing Two Religions in One Interfaith Family is available now in hardcover and eBook from Beacon Press.