It was yet another unseasonably hot day when Bob and I struck out from Glendalough in the direction of Baltinglass, which brought us nearer to Brownshill Dolmen. Officially known as the Kernanstown Cromlech, this portal tomb has a capstone weighing between 100-150 tons, which is reputed to be the biggest in Ireland and all of Europe.

A modest parking lot along a quiet country road marked the beginning of a short hike to the tomb where some believe that religious rites were once held.

Bob and I soon discovered that the tomb was peacefully located in the center of a farmer’s field with crops gently undulating on all four sides. We could not have asked for a more perfect day to seek out the ancient burial site. A big blue sky hugged the horizon, and soft clouds cast the occasional shadow over the flowing sea of green.

To some, the capstone might look like some old boulder unearthed when early farmers tilled the soil for their crops, and, in actual fact, the tomb may have, at one time, been covered by a mound of earth or a cairn of rocks. But the assemblage of the rocks into a portal tomb would have occurred sometime between 3800-3200 BC using huge blocks left behind by glaciers during the Ice Age.

It was pleasant walking along the protective hedgerows bordering the farm fields in order to gain access to the little plot where the dolmen prominently stood. With no other visitors in sight, we found the location quiet and secluded, a reprieve from the confines of our car.

Adding to the pastoral beauty of the location was the occasional wild poppy that added a punch of color to the wavy depths of green grass and swaying stalks of spindly buttercups.

As Bob and I strolled along the shade-dappled trail, we caught sight of a small yellow bird where it perched on top of a fence post. It turned out to be a Yellowhammer (Emberiza citrinella). This is a species of bird that breeds across Europe and parts of Asia, but the species has been in serious decline throughout Europe in recent years.

I believe this to be a male Yellowhammer because of the heavily streaked brown back. With the adjacent crops forming a dense mass of vegetation, both a harbor for insects and a source of weed seeds, the Yellowhammer had a good habitat for foraging and nesting in the surrounding fields.

Once Bob and I entered the fenced-off area designating the protected site, we saw the small plot of manicured grass to be dominated by the massive capstone of the neolithic Portal Tomb. It makes one wonder how a primitive Stone Age community could manage to move the humongous rock without modern engineering skills.

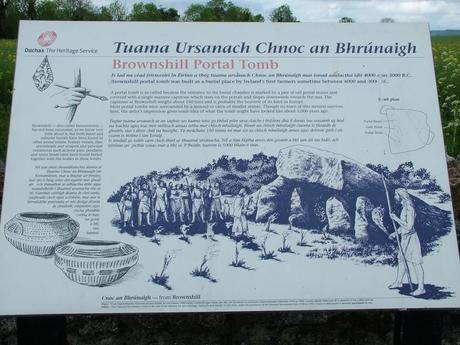

With a gentle breeze tousling my hair, I paused to read the literature on site and learned that the portal tomb was built as a burial place by Ireland’s first migrant farmers sometime between 4000 and 3000 BC. It has endured for a very long time.

The picture featured in the display shows how the tomb might have appeared some 5000 years ago, bolstered by a mound of earth to the rear, and with an elaborate entrance area consisting of several stones for the facade. The completed tomb was called a barrow or burial mound.

That early covering of earth and/or rocks has weathered away, leaving only the stone skeleton of the burial mound intact.

As you see in Bob’s short video, the prominent remains today include the 100-ton granite capstone, 2 portal stones that define the entrance that is blocked by a central stone or gate stone, and a prostrate slab.

There is something eerily haunting about such sacred spots as this portal tomb, and as I circled the assembly of boulders, the transient coolness of the morning air touched my face and mind alike, dispelling the conjured spirits in my imagination.

The massive blocks of stone that supported the capstone were, in their own right, very impressive and required the farmers to inset them into the ground at great depths for stability and longevity.

Bob put his mind to the test trying to figure out how the Stone Age people accomplished the positioning of the megalithic capstone and gargantuan portal stones of this neolithic grave site.

Portal tombs were single-chamber graves wherein the cremated body of the deceased was placed, often with beads, pottery and stone artefacts.

It has been suggested that such megalithic tombs were more than mere burial places, but instead, were monuments to ancestors or even served to declare territorial rights. Bob and I spent considerable time contemplating the significance of this tomb, said to have been erected to honor a local chieftain.

We were respectful and did not enter into the tomb even though evidence showed that others had done so. Being at an out of the way location, no custodian is on hand to keep an eye on the sacred place. In fact, large stones lying next to the nearby field boundary are believed to be from this tomb, but when and how they were moved is unknown.

Two other megalithic portal tombs are thought to have existed close by, but they did not survive the passage of time. But the Brownshill Dolmen will remain where it has always been, an homage to spirits that have gone before us and a reminder of the achievements of Stone Age man.

Checkout some of our other Ireland postings

Glendalough, one of the most beautiful places in Ireland

Powerscourt House and Gardens, A World Of Floral Glory – Ireland

Driving the Intriguing Backroads of Wicklow County – Ireland

Hiking In Wicklow Mountains National Park – Ireland

Frame To Frame – Bob & Jean