Celebrating with friends, December 1963.

While letters congratulating Linus Pauling for winning the 1962 Nobel Peace Prize continued to pour into his office early in December 1963, the debate in the press over whether Pauling deserved the Nobel had begun to cool down. Meanwhile, closer to home in southern California, friends and colleagues of Pauling and his wife Ava Helen honored the pair for their activism at several events.

On December 1st, eight activist groups, including Women Strike for Peace, the American Friends Service Committee, SANE, and the Youth Action Committee, held a public reception for the Paulings at the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics in Los Angeles. The Paulings also opened their home to celebrate with friends and former students. The celebrants made banners to honor the Paulings, one reading, “We knew you when you only had one.” Another took on a more mathematical form: “LP plus AHP equals PAX plus 2 Nobels.”

While the Pauling’s attended celebrations in their honor, they were obliged to refuse other offers as they prepared for their trip. A Caltech student requested that Pauling give a farewell speech before leaving for Scandinavia. Turning down the request, Pauling would tell the Associated Press a few days later that he was not giving any speeches before he accepted his Nobel Prize so as not to “be tempted to let something drop beforehand.”

Flyer for the Biology Department coffee hour honoring Pauling’s receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize. December 3, 1963.

It is, of course, entirely possible that something else was in play with respect to Pauling’s refusal to speak at Caltech. Much has been made of Caltech’s official non-response to Pauling’s Nobel Peace award. Indeed, the only recognition that occurred at all on the Pasadena campus was a small coffee hour hosted by the Biology Department. The fact that his own department, to say nothing of the larger institution, chose to ignore this major decoration was deeply hurtful to Pauling. By December Pauling had already announced his departure from Caltech, his academic home of some forty-one years. But the cold shoulder that he received from all but the Biology Department was suggestive of tensions that had been mounting for some time and proved a fitting, if bitter, capstone to this unhappy phase of his relationship with the Institute.

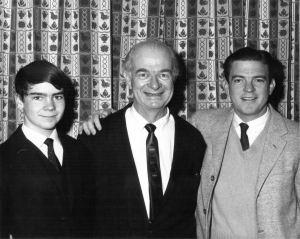

Three Linus Paulings. From left, grandson Linus Fowler Pauling, Linus Pauling and Linus Pauling Jr. 1963.

For their part, mainstream journalists had finally begun to take a more amicable and celebratory approach to their portrayals of Pauling than had generally been the case since the announcement of his Nobel win in October. Articles sought a more personal reflection of Pauling while not completely ignoring the earlier controversy.

Of particular note, as the Paulings flew across the Atlantic on December 7th, the Honolulu Star-Bulletin published an interview with their eldest son, Linus Pauling Jr., in which he reflected on his father’s activism. When asked to gauge Pauling’s talents, Pauling Jr. downplayed his father’s peace efforts in relation to his work as a scientist. “In terms of his ability to marshal facts and to organize and reorganize them toward a goal,” Pauling Jr. stated, “his strivings for peace are comparatively simple, whereas this ability applied to science demonstrates an astoundingly high degree of creative imagination. Essentially, his work in peace is a public relations job – to get the facts across to the public in a meaningful way.”

When asked what inspired his father to engage in peace work, Pauling Jr. said that “innately, he has always been a humanitarian.” His aversion to hunting and his resistance to Japanese internment during World War II were submitted as past evidence of these humanist proclivities.

Digging a little deeper, Pauling Jr. pointed to his father’s experience with Bright’s disease in the early 1940s as a turning point in taking on social issues. At the beginning of the disease, which manifested in bloating and impaired kidney functioning, the elder Pauling “was pretty close to dying.” During his recovery he was forced to rest and spent time weaving blankets. Pauling Jr. thought that his father’s time of rest “forced him to contemplate on the value of life; on the wrongs of killing and harming that was going on around the world.”

Ava Helen Pauling also was a major influence on her husband according to Pauling Jr. Of particular importance was her work with Union Now during the early war years – an activist platform that called for world government as a tool for mediating international issues between nations.

Pauling Jr. inevitably addressed some of the controversy surrounding his father’s alleged communist ties, saying that he had “never heard him praise communism, although, on occasion, he has criticized some aspects of capitalism, such as unequal opportunities. Today,” he continued, “that’s known as civil rights.”

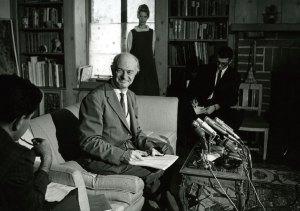

Conducting interviews in the living room of the Pasadena home, 1963. James McClanahan, photographer.

The following day, an Associated Press article that centered on Pauling’s life and his “book-and-paper strewn den,” came out in papers across the country. With the Nobel ceremonies only two days away, the headlines that ran with the article insinuated something big, with variations of “Pauling Hints at Surprises in Oslo Speech,” “Linus Pauling Promises Speech Shocker,” or “Pauling Predicts Shock.” The actual feature article, written by Ralph Dighton, was less sensational.

A Peanuts cartoon strip signed by Charles Schultz on display at the Pauling’s home helped Dighton to characterize his subject. The strip showed the animated character Linus stacking blocks in a “gravity-defying stairstep fashion” with the tagline, “Linus, you can’t do that!” Pauling’s own reaction after reading it, Dighton noted, was a loud laugh. For Dighton, the lesson of the cartoon was that “the world has been telling Pauling [you can't do] that all his life, and he keeps doing what for many others would be impossible.”

In his piece, Dighton also spoke to Pauling’s decision to leave Caltech in favor of the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions. Pauling avoided any discussion of problems at Caltech and instead explained that receiving the Nobel Peace Prize was an opportunity and his decision to leave was a direct consequence of his prize. At the Center, Pauling would have more freedom to focus on his peace work and international affairs while also continuing to delve into the molecular basis of disease.

While the article avoided adding to the controversy surrounding Pauling, it still discussed past instances to remind readers that Pauling was never far from trouble. The list was familiar to those who had followed Pauling’s career: the 1952 denial of Pauling’s passport due to suspected communist tendencies; his1958 petition against nuclear testing, signed by over 11,000 scientists from 49 different countries; the consequent 1960 “joust” with the Senate Internal Security subcommittee; his picketing of the Kennedy White House just before attending dinner inside. All helped to exemplify how Pauling had “made a public scourge of himself.”

Arrived in Oslo. From left, an SAS official, Ava Helen and Linus Pauling, Linda Pauling Kamb and Barclay Kamb, Lucy Pauling, Crellin Pauling and Linus Pauling Jr. December 1963.

As Pauling set his sights on Europe and the spotlight of international attention, he left behind a busy office. His assistants Helen Gilrane and Katherine Cassady, who had typed up numerous thank you letters and helped to coordinate Pauling’s increasingly busy life over the previous two months, continued to assist Pauling from a distance. Both kept on answering Pauling’s unceasing correspondence while also working out the details of his still-unfolding trip. For her part, Gilrane responded to Bertrand Russell among many others, telling him that Pauling would be unable to respond right away. Communications of high importance were forwarded to Pauling in Norway; others had to wait until his return in January.

The Paulings return trip through the East Coast had not been finalized either. Gilrane made reservations in New York and Philadelphia while also coordinating Pauling’s wardrobe for the celebrations that would take place upon his return. She wrote to Samuel Rubin, President of the American-Israel Cultural Foundation, that Pauling “shall have his smoking jacket as well as his tails, but he will wear whatever you think is appropriate for the evening.”

Pauling also benefited from the help of friends in Norway. Otto Bastiansen, a Norwegian physicist and chemist, worked out much of Pauling’s Scandinavian itinerary, deciding where he would lecture and with whom he would meet. Since the entire Pauling family, including the children’s spouses, was coming, Bastiansen had to work out how they might be involved in activities as well. The Paulings’ first event happened almost as soon as they landed in Oslo on Sunday, December 8th. Ignored by the U.S. embassy or any other official representative from his home country, Pauling was welcomed at a private party held at the home of Marie Lous-Mohr, a Norwegian Holocaust survivor and peace activist who had also helped to arrange Pauling’s schedule.

On December 9th, the day before the Peace Prize ceremonies, the Paulings had lunch with friends and colleagues from Norway at the Hotel Continental, where they were staying. Afterward Linus and Ava Helen, together with two of their sons, Peter and Linus Jr., participated in a press conference. The event focused mostly on the man of the hour, who was very optimistic about the significance of receiving the Nobel Peace Prize and expressed gratitude toward the many people who worked in the peace movement. The Associated Press quoted Pauling as stating,

I think awarding me the prize will mean great encouragement to the peace workers everywhere, but particularly in the United States, where there have been so many attacks upon the peace workers… For some time it has been regarded as improper there to talk about these things. I think this is about the best thing that could happen for the movement.

As the world was still mourning the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Pauling said that Kennedy’s “attitude” helped make peace activism acceptable in the United States. Pauling steered away from any criticisms of Kennedy, as one reporter prodded Pauling about his opinion of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. At the time, Pauling had been extremely critical, calling Kennedy’s threat of military action against Russia “horrifying” as it could easily lead to the use of nuclear weapons. Regardless, Pauling told the press in Oslo that the situation “taught the lesson to the world, that the existence of nuclear weapons is a peril to the human race.”

The next day, Pauling would receive the Nobel Peace Prize for helping alert the world to that peril.