[Ed Note: With the conclusion of the academic year here at Oregon State University, we say goodbye to Student Archivist Ethan Heusser, who has written extensively on the Special Collections and Archives Research Center’s rare book collections at our sister blog, Rare@OSU. Today and over the next three weeks, we will share three Pauling-related posts that Ethan wrote over the course of his tenure working for us.]

Many Americans – and people around the globe – experienced the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s as an age of political uncertainty and social turmoil. It was a powerful time: everywhere the specter of disaster loomed, yet that fear brought with it a unique capacity for change enabled by commonplace desperation. In the United States alone, mounting resistance to the Vietnam War built confidence among grass-roots activist organizations for their efficacy in up-ending the status quo. And while mutually assured destruction terrified the world, the threat of nuclear war also inspired many thinkers and activists to strive for equally bold solutions. In the light of world chaos and potential mass destruction, the idea of building a global government and abolishing nationalism seemed especially promising – far more promising than what the United Nations seemed ultimately able to provide.

It’s no surprise, then, to see a large proliferation in world peace literature in the Cold War era. Some publications were mild and innocuous, but many took the form of bold declarations and manifestos about the urgent need for radical change.

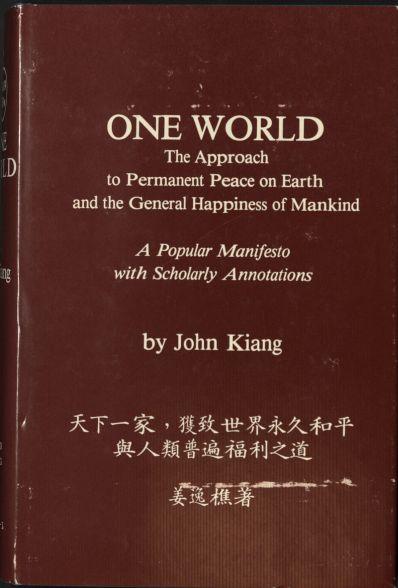

An excellent example of the latter is One World: The Approach to Permanent Peace on Earth and the General Happiness of Mankind by John Kiang. Self-described as “a manifesto of revolution for world union with the evolutionary law of group expansion as a guiding theory,” it examines shifting technologies and living conditions to build a larger argument in favor of a unified humanity. From that perspective, nations and nation-states can only be seen as counter-productive: the deep-seated but fundamentally arbitrary veil of nationalism impedes sincere appeals to common humanity and mutual accountability.

Although the core text is fairly concise, this copy of One World is a scholarly edition from 1984, replete with extensive sources, commentary, and analysis:

In this work we see the role that cultural context can play in international movements: though not explicitly outlined, One Worldcontains thematic and rhetorical ties to the utopic vision of “Great Unity” in China. Great Unity represents the goal of creating a Chinese society of mutual accountability and selflessness – a cohesive community where people work to help others rather than harm them.

First described in classic Chinese texts going back millennia, Great Unity was popularized by Sun Yat-Sen in the early 20th century. In doing so, it was used to help build a cultural momentum in favor of a shift towards a communist ideal. The Great Unity message was adopted overtly in China’s national anthem in 1937; though later supplanted with another song in the People’s Republic of China during the Chinese Civil War, it remains in use by Taiwan to this day.

John Kiang left China in 1949 in the wake of the earth-shattering Chinese Civil War. It seems fair to suggest that he nevertheless brought the culturally-specific vision of world peace, prosperity, and harmony with him stateside. It’s hard for those of us living in our countries of birth to imagine the inner turmoil he must have felt during that time, working for global peace a world away while his homeland was experiencing such complete upheaval and division. Perhaps that effort helped him, in some way, to bring his home with him and improve the world as a result.

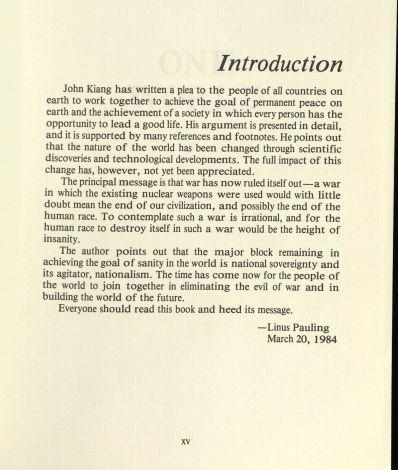

These efforts manifested in One World. Though a relatively obscure book, One World at last found some degree of traction once it found its way into the hands of two-time Nobel Laureate Linus Pauling – surprisingly, Pauling was willing to attach his name to it in the form of a guest introduction.

As a famous peace activist, Pauling was a prime recipient of unsolicited manuscripts, book ideas, calls for action, and reference requests. But of all of the texts he received and was asked to endorse, why would he choose one such as this?

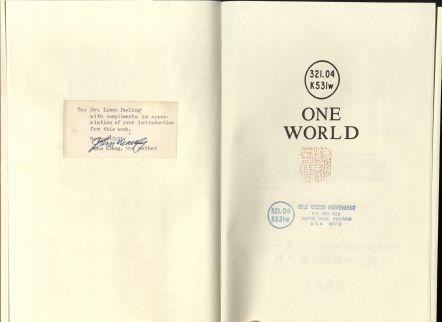

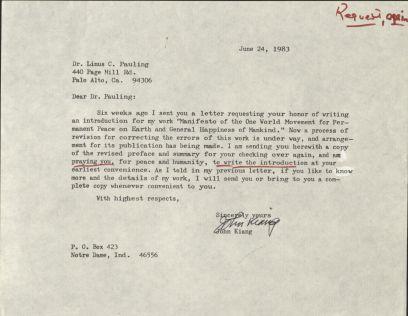

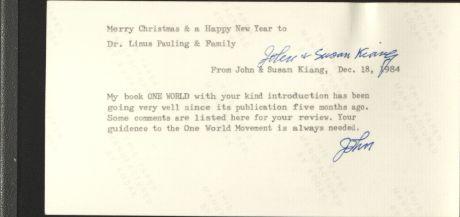

A large factor was undoubtedly Kiang’s persistent correspondence with Pauling. He wrote with Pauling repeatedly between 1983-4, praising Pauling’s efforts and experience and asking for an introduction to One World. Pauling consistently refused, citing his lack of expertise in Kiang’s specific subject area. This pseudo-humble approach to refusing unsolicited (and often wacky) manuscripts was trademark for Pauling during his peak social activism years. Then, somehow, everything changed for One World. Somehow, Pauling changed his mind. We have as proof Pauling’s written introduction documented in the Ava Helen and Linus Pauling Collection, along with letters and cards from the Kiang family thanking him for his collaboration:

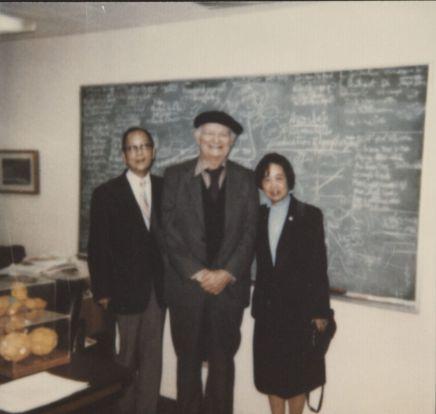

Even when meticulously compiled and researched, correspondence collections can still resist post hocscrutiny. We hold a substantial set of letters between the two activists, but we lack the connection point between the “before” and “after” of when Pauling agreed to add his name to Kiang’s One World project. Was it a letter that went missing? A phone call? An in-person visit? Kiang later sent Pauling a photo of a meeting between them, but the context for how and when it happened is largely absent.

Another probable factor is that the content and message of the book aligned well with Pauling’s driving fears for the future. As Pauling writes in his introduction, “[Kiang’s] principal message is that war has now ruled itself out.” For Pauling, the atom bomb meant that “a war in which the existing nuclear weapons were used would with little doubt mean the end of our civilization, and possibly the end of the human race.” Perhaps that in itself built enough common ground between two men of different backgrounds and fields of expertise to collaborate – if only in a minor way – on what must have felt like a higher calling. (Pauling’s endorsement would be used in later work by John Kiang as well, but always from a distanced position.)

On a general level, One Worldembodies the slippery way that ideas persist, spread, and evolve. Just like how John Kiang built his own vision upon seeds planted by Sun Yat-Sen and many authors before him, it will be fascinating to witness how the Cold War push towards internationally-regulated peace and world government will rear its head again on the world stage in the decades to come.