Note: You might have noticed that it’s been a while since we last updated (almost 6 months actually). We have been home for that whole time and we didn’t want to update until we had this – an edited version of an article I wrote for the travel section of the Irish Independent.

I remember being conscious of the bead of sweat trickling down my nose as I pressed my back against the wall. I was face-to-face, toe-to-toe with a Brazilian drug dealer, his rifle cold against my shoulder as he brushed past. In the stifling heat of Rio de Janeiro’s slums, the cool touch of metal was the only relief from the rising humidity.

A month later I would be watching news reports on a police siege of the slums that left at least 45 dead. But that day I felt safe in the favelas. I believed my tour guide Luiz’s soothing words. “Don’t worry,” he said, “they usually only use their guns to fire in the air to signal that the police are coming.”

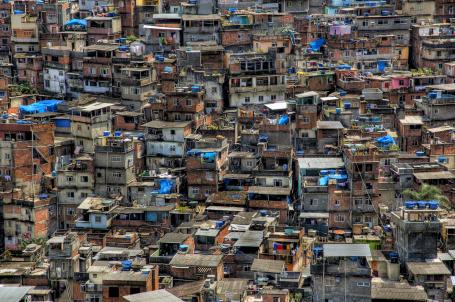

As we wound our way down alleyways too tight to accommodate a pram, between the hotchpotch redbrick shacks – one stacked clumsily on top of another – we passed huge mounds of putrefying rubbish stowed in every available space. We backed into walls to let pregnant women, drug dealers and schoolchildren past; the kids happily swinging their backpacks and tearing around corners on their headlong rush home; the dealers chatting lazily to friends, cigarettes dangling from idle fingers.

By the time we had reached the centre of the favela (slum) a whole other world had revealed itself. While gun-toting boys selling cocaine patrolled the edge of the neighborhood, the centre was a refuge for thousands of families. Here teenagers banged out samba rhythms on empty buckets, women hummed as they draped their washing on lines, dogs stretched out in isolated cracks of sunlight yawning widely and shopkeepers sat out on their stoops tapping their toes. From the staff at the local juice bar to joggers on the beach, everyone in Rio de Janeiro was moving to their own beat and in the favela I was learning that that beat was surprisingly uplifting. Slowly I started to lower my guard, letting out a deep breath I hadn’t realised I was holding.

With Luiz leading the way, we climbed four floors up a cramped staircase, sidestepping crumpled steps briefly illuminated by flickering neon lights. At the top we shoved through a splintered door and gazed upon one of Rio’s most memorable sights. On the roof of the city, far away from tourist board images of Carnival, volleyball games on the beach and Christ the Redeemer, we were presented with a view of Rio not usually printed on postcards.

Dripping from every hill and valley was a sea of houses. In the early afternoon it was strangely mundane. Mothers collecting their kids from school or folding coloured sheets that flapped in a rare breeze, old men fanning themselves on their stoops and teachers keeping a close eye on their lunching wards at a nearby playschool.

“Life here,” said Luiz as he stepped out onto the roof, motioning to the scene in front of us, “is not as bad as people say. Many people live here and work in the city. For many families this has been home for generations. Their parents lived here, as did their grandparents and in the future their children and grandchildren will be raised here. There is community here. Life in the favelas isn’t perfect of course, but what neighbourhood is?”

Listening to the rhythm of life in the favela it wasn’t hard to see it as the birthplace of samba. Between the towering houses, suffocating alleyways and looming shadows came dizzying cracks of light. The screeching sound of little girls reciting a skipping chant rose from the streets below and mingled with the sultry tones of Amy Winehouse drifting from a nearby window. Leaves rustled. Luiz drummed his fingers. Doors slammed. A mother called out to her children. Electricity lines fizzed. A gunshot cracked through the sticky air.

Of course there was much more to Rio than just the favelas. We spent a lot of time people-watching on the beach, we climbed up to see Christ the Redeemer and we partied hard. One major highlight was our night at the street party in Lapa – a weekly occurrence for those lucky enough to live in this magical city.

In a word, it was immense. Samba bands filled the night with music and hoards of tourists and locals of every age filled several blocks. People lounged on the colourful Lapa steps chatting to friends and strangers; restaurants spilled out onto pedestrianised streets; laughing vendors sold homemade caipirinhas and street food from rickety tables; and some incredibly friendly locals showed us how to shake our (completely insufficient) hips to the beat of a drum. As a wise woman once said, I could have danced all night.

Rio was the perfect end to a perfect trip. The Cariocas really have it sussed – rollerblading to work, spending lunchtime on the beach, eating out on weekdays and dancing until dawn. We made two new Kiwi friends, laughed a lot and then, when it was time to leave Fla, cried a lot (well I did anyway.) How could it be time to go home already? In ways it felt like only yesterday that we had left, shaking with excitement and fear. But in other ways it felt like a lifetime. We had done so much in only 12 months. We had climbed the Great Wall of China, dived the Great Barrier Reef and hiked to Machu Picchu. I’d lost half my face to a Vietnamese Road, we were chased off a desert island by monkeys and we were poisoned by a yak stew near Tibet. We had also made more friends than we could count – friends that hopefully, we would keep forever – and perhaps most notably, we had survived an entire year together with little or no drama. And no breakups! Year long breakup indeed, I guess this thing is going to go on longer than we had expected.

There are more pictures from Rio de Janeiro available in the gallery