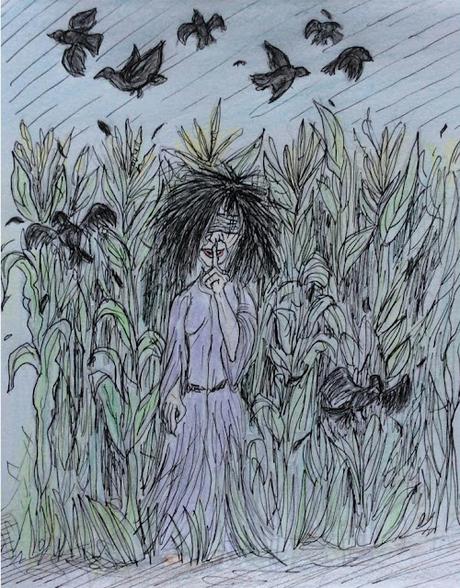

the Witch

Permit me what seems like something of a leap: there is a link here, I assure you. For it is my belief that the ancient archetype of the Witch not only manages to encompass all of the above representations, and doubtlessly many more, but that she also embodies this omnipresent fear of the unknown. Or perhaps a better way to phrase it: she represents the fear of coming to know that which we’d prefer not to, of introducing into our world knowledge we’d rather remain ignorant of, or that which we presume to feel better or safer without knowing. For once such knowledge is introduced, our worlds are corrupted and will never be the same again.The Witch is this agent of change, and she does so by seeking and delivering secret or forbidden knowledge. This is knowledge outside of the mundane or common sense, obtained through deep study, trial and initiation that delves beyond the domains of where most dare, or are permitted, to look. She appears in times of great upheaval, and is not usually welcomed for it, for she brings forth ideas that threaten to destabilise the current order.Often, we are resistant to change despite its inevitability, and have a tendency to cling to the structures of that which we know. But the Witch cannot be ignored – for she arises as a result of a society’s or an individual’s refusal to face that which it has avoided or suppressed for far too long. It is no accident that the witches in our storybooks are placed beyond the boundaries of civilisation, in that mysterious domain beyond civilised thought, deep within the untamed forest, hermits housed in the heart of the wilderness, the embodiment of our repressed desires cackling at the fringes of society, the primordial realities mocking the fragility of our manmade constructs and convictions, a reminder that there is much still which resides beyond the conquest of our known worlds.She is that novel piece of information appearing out of the Stygian depths of our unconscious. The sudden interjection of a single thought that changes the course of a person’s life. The power of the Witch cannot be underestimated, and it is telling that in our current times of great upheaval, in which all the grand narratives and ‘truths’ of the previous century are being torn down, re-examined or rewritten, that the Witch is being reclaimed, shorn of her negative connotations and reinvented as a positive icon.Though the Witch has taken many forms throughout the ages, the residual image we modern westerners have inherited is the surviving relic of a propaganda campaign that spanned centuries. And the instigators of this propaganda? The Christian church of course.The church held a very clear ideal of what a woman should be. The main cornerstones of this ideal were that women were subordinate to men and held no authority over them, effectively making them second-class citizens, and this was the natural order of things. Their role was in bearing and raising children, cooking, cleaning and maintaining the household. Any woman that acted contrary to this presented a threat to the male-dominated social matrix, and the church needed a means to persecute and punish such women lest their behavior spread dangerous ideas.Enter the Witch as we know it: the malevolent crone, usually impossibly old, who lives outside the purview of society, unmarried and alone (the sheer horror of the independent woman), who does not produce children but would rather consume them (often characterised as ‘unnatural’ for not wanting children, for not being able to have them, or otherwise disliking them), is sexually promiscuous and often ‘tricks’ men under the guise of a temptress (god forbid a woman take charge of her sexuality), composes her own faith and does not attend church (and therefore, was in league with the Devil), a deft exponent of black magic and a spitter of hexes and curses, all in a concentrated effort to unleash misery, pain and all matter of hellish woe upon poor and unwitting, God-loving, townsfolk.The church had woven into the local mythology a character presented as an abomination of everything a woman should be. They not only created a scapegoat to blame for society’s ills, to be driven out or better yet: extinguished entirely (cue hangings, beheadings and burnings at the stake), but also a means to control the populace and police their behavior.Through the monstrous image of the Witch, they vilified undesirable qualities by exaggerating them to grotesque proportions. The woman who valued her life would think twice before embodying such qualities, and the everyday citizen was provided a criterion by which they could suspect and rat out their neighbours.It is worth noting that regardless of gender, anyone could be accused and tried as a witch. Though it does say something that of all witches accused and tried, around eighty percent were women. The witch-hunts that spanned from the fifteenth to the late eighteenth century were one of the most horrific and successful acts of gynecide to haunt our recorded history. That the powers that be felt that such campaigns were necessary can only speak to the gravity and importance of ideas which challenge the status-quo.When we invoke the spirit of the Witch, that is exactly what we are doing: questioning the status quo. It is the act of seeking out answers beyond the realm of that which we know, and admitting that there is more to learn beyond the constructs of our present understandings. That the Witch was characterised as the devil’s advocate suits her symbology perfectly, for she represents the voice unafraid to challenge the existing paradigm.She captures the anarchic spirit of a people determined to live in opposition to the expectations of society. Theirs is to test the strength of, or outright dismantle, societal boundaries lest those boundaries rigidify and become the prison walls in which a society traps itself. After all, the ongoing survival of any society depends upon its ability to question itself, to adapt and change with the times.Josh LonsdaleEmail ThisBlogThis!Share to TwitterShare to Facebook