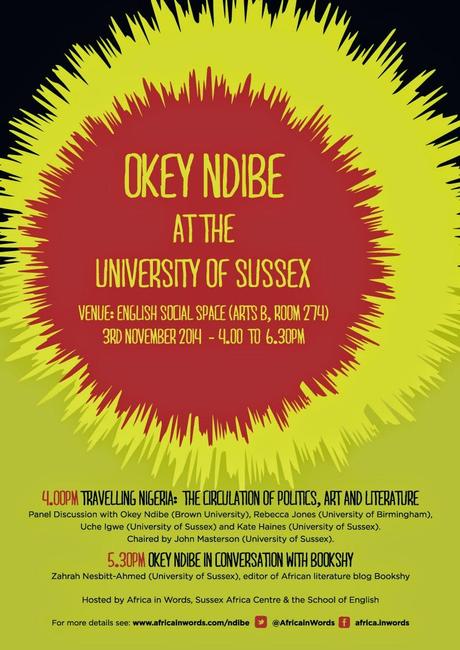

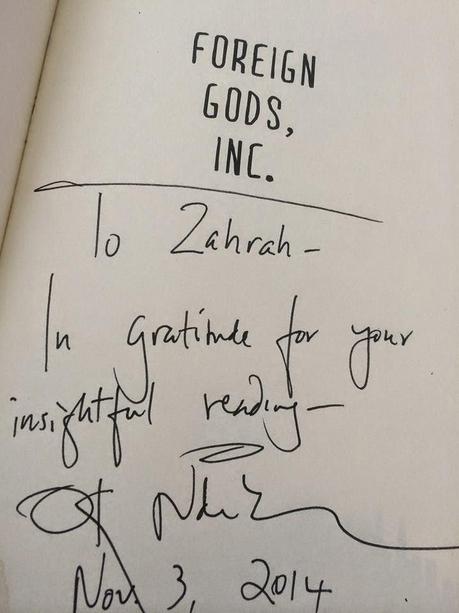

For almost two weeks, Okey Ndibe was in the UK on a tour. In that time he was a featured speaker at the Arrow of God at 50 Conference and visited a number of UK cities and universities including University of Bristol, Blackwells in Newcastle, University of Birmingham, Centre for African Studies at SOAS, and Book and Kitchen in London. His last stop was at the University of Sussex, an event hosted by Africa in Words, Sussex Africa Centre and the School of English. So on Monday November 3rd, I got to meet and interview Okey

Ndibe. This was after an insightful panel discussion on travel, politics,

literature and Nigerian writing at the University of Sussex.

For almost two weeks, Okey Ndibe was in the UK on a tour. In that time he was a featured speaker at the Arrow of God at 50 Conference and visited a number of UK cities and universities including University of Bristol, Blackwells in Newcastle, University of Birmingham, Centre for African Studies at SOAS, and Book and Kitchen in London. His last stop was at the University of Sussex, an event hosted by Africa in Words, Sussex Africa Centre and the School of English. So on Monday November 3rd, I got to meet and interview Okey

Ndibe. This was after an insightful panel discussion on travel, politics,

literature and Nigerian writing at the University of Sussex.  As part of the panel, Travelling Nigeria: The Circulation of Politics, Art and Literature, Okey Ndibe spoke on

literature always being pertinent to the way people's images are formed

and how Independence was the opportunity to reshape the narrative of

Africans that existed. Ndibe

explains that Nigeria was a country conceived in hope, but nurtured into

hopelessness by its leaders but also its citizens and how as a

columnist he is harsh towards Nigeria, which is currently a portrait of mediocrity

and failure. This he says because he is confident that Nigeria can do

better. His talk centred on how the image of Nigeria has become an

important subject matter for writers and quoting Teju Cole explains that

'the writers obligation isn't to show a good picture. It is to show a

real one' (I am paraphrasing here). He explains how Nigerian literature

reflects 'this angst, this sense of disillusionment that we aren't where

we need to be' and how through writing we are holding a mirror up in

the hope that we will do better.

Following on from Okey Ndibe, Rebecca Jones, from University of Birmingham, spoke on Nigerian travel writing, such as Folarin Kolawole and Pelu Awofeso, who project a very positive view of Nigeria through their writing. Uche Igwe, from University of Sussex, brought a political perspective and explored the role of literature, and particularly the works of Achebe (The Trouble with Nigeria), Soyinka (The Trials of Brother Jero) and Ndibe (Foreign Gods, Inc.) in politics and corruption. His presentation focused on how everyone in Nigeria is trying to take his/her own national cake. Finally, Kate Haines (also from Sussex) and from Africa in Words explored the relationship between memory, history and how texts travel. She used the case of Farafina Press and their role in making Adichie's Purple Hibiscus big in Nigeria. A write-up of the panel can be found on Africa in Words.

As part of the panel, Travelling Nigeria: The Circulation of Politics, Art and Literature, Okey Ndibe spoke on

literature always being pertinent to the way people's images are formed

and how Independence was the opportunity to reshape the narrative of

Africans that existed. Ndibe

explains that Nigeria was a country conceived in hope, but nurtured into

hopelessness by its leaders but also its citizens and how as a

columnist he is harsh towards Nigeria, which is currently a portrait of mediocrity

and failure. This he says because he is confident that Nigeria can do

better. His talk centred on how the image of Nigeria has become an

important subject matter for writers and quoting Teju Cole explains that

'the writers obligation isn't to show a good picture. It is to show a

real one' (I am paraphrasing here). He explains how Nigerian literature

reflects 'this angst, this sense of disillusionment that we aren't where

we need to be' and how through writing we are holding a mirror up in

the hope that we will do better.

Following on from Okey Ndibe, Rebecca Jones, from University of Birmingham, spoke on Nigerian travel writing, such as Folarin Kolawole and Pelu Awofeso, who project a very positive view of Nigeria through their writing. Uche Igwe, from University of Sussex, brought a political perspective and explored the role of literature, and particularly the works of Achebe (The Trouble with Nigeria), Soyinka (The Trials of Brother Jero) and Ndibe (Foreign Gods, Inc.) in politics and corruption. His presentation focused on how everyone in Nigeria is trying to take his/her own national cake. Finally, Kate Haines (also from Sussex) and from Africa in Words explored the relationship between memory, history and how texts travel. She used the case of Farafina Press and their role in making Adichie's Purple Hibiscus big in Nigeria. A write-up of the panel can be found on Africa in Words.

The panel lasted close to two hours and while thoroughly enjoying the discussions I was also slightly panicking about the fact that my Q&A session was slowly approaching and I was asking myself – have I chosen the right questions to ask, will my focus not be academic enough for the space, would people be extremely bored listening to me questioning Okey Ndibe, would people even stay after the first session? Yes, even with seconds leading up to me walking to the front of the room to begin the session I was still terrified. Thankfully, once we started talking my nerves disappeared and it was truly amazing to sit with Okey Ndibe and have a conversation about Foreign Gods, Inc. Forgetting that my phone did not have enough space, I was unable to record the interview so this post is me pulling together my scribbles and thoughts to capture what I remember of my conversation with Okey Ndibe.

PS. I tried to summarise as much as I could, but as I also really wanted to give justice to the conversation just a heads up that this post is longer than usual, but it's worth it.

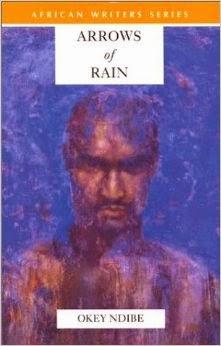

The interview began with me asking Okey Ndibe why he was here in Obodo Oyinbo, with Ndibe talking briefly about the UK’s strong engagement with [African] literature over time. From there, Okey Ndibe took us on the journey of getting Foreign Gods, Inc. published following his first novel Arrows of Rain and the changing landscape of African literature in the last 14/15 years. For instance, when Arrows of Rain was first published in 1999 his default was Heinemann’s AWS. Fast forward today and Foreign Gods, Inc. was published by Soho Press.

That aside, Arrows

of Rain did exceptionally well under Heinemann and the year it was published it

became their bestselling novel in the last ten years. With the success of his

first novel, Ndibe's publisher wanted him to bring out a second novel as soon as possible. Yet, as Okey Ndibe explained, he is quite a slow writer. Comparing the writing of a sentence to a one-night stand, where you wake up the morning after the night before and ask yourself if you really brought that person home last night, Ndibe noted how sometimes he writes a sentence only to wake up the next morning asking himself if he really brought that [the sentence] home last night. So publishing his second novel took time.

That aside, Arrows

of Rain did exceptionally well under Heinemann and the year it was published it

became their bestselling novel in the last ten years. With the success of his

first novel, Ndibe's publisher wanted him to bring out a second novel as soon as possible. Yet, as Okey Ndibe explained, he is quite a slow writer. Comparing the writing of a sentence to a one-night stand, where you wake up the morning after the night before and ask yourself if you really brought that person home last night, Ndibe noted how sometimes he writes a sentence only to wake up the next morning asking himself if he really brought that [the sentence] home last night. So publishing his second novel took time.

Not only was Foreign Gods, Inc. 14 years in the making, it was also initially an entirely different story - a whodunit tale following about a Western anthropologist in Africa who goes to a (I am assuming Nigerian) village to solve the mystery of another missing Western anthropologist and the ‘wrestling of languages’ and culture. In Native Tongues (the title of this sadly never published novel) the female character would, for instance, fail to understand a lot of the proverbs the people in the village used, grossly misinterpreting them. In the end the things lost in translation meant she was unable to solve the mystery. That book never came to pass. Instead, another story was being brewed - and inspired this time by a cousin of Okey Ndibe who owned a shop called Afrique in Cambridge, Massachusetts that sold African wares.

Okey Ndibe speaks about his cousin telling him about a deity in Ndibe’s hometown being stolen, but two weeks later it was returned. Ndibe wanted to know what would lead a person to do such a thing, especially as this deity he said ‘had a dreadful reputation’. So, when his publisher wanted another book, he said he would write a short story around this premise – even though as he explained ‘I have never succeeded in doing a short story’.

Foreign Gods, Inc. started out as a short story, and 1200 pages later and 6 years later and 4 years of cuts he sent it to his editor who said it was ‘captivating and fascinating’. I was curious about the whole middle of the book that was taken out and good news, it isn’t all lost – it is currently being reshaped into a novel. Foreign Gods, Inc. was also initially going to be about an Evangelical Christian pastor whose mission was to get his congregation in the village to destroy this deity.

Having given us insights into the genesis of Foreign Gods, Inc., Okey Ndibe then went on to introduce the novel to the audience and spoke about how in America there are ‘millions of people who did all the right things but didn’t succeed’. Ike, his character in Foreign Gods, Inc., was one such person. Before going on, I got a lesson on the correct pronunciation of Ike (pronounce Ike the wrong way and it might sound like buttocks in Igbo). In the end while I was not pronouncing Ike as buttock, I also was not really pronouncing his name the right way - I was somewhere in between. Still, as long as I was not saying buttocks I was happy.

inhabitat.com

Back to Ike. He graduated with a good degree in economics from a really good university, but could not find a job and works as a taxi driver.One of his downfalls was his accent. I asked Okey Ndibe why the focus on accents given the many difficulties immigrants face? To which he explains that it symbolises many other barriers. He speaks about two men with PhDs he knew who were extremely smart but could not find jobs because of their accents, and so ended up driving cabs. They had the qualifications and wanted to teach but it was hard. He explained how one of them would pronounce KLM as ‘KAY – ELL – EMM’ (stressing all the letters) and his r would be heavily rolled ‘rrrrrr’. He explained how accents are a clear sign of ‘the otherness’ of immigrants.Ike was also just really unlucky, at every step of the way he kept on falling into one spot of bad luck or the other, and I broached that subject . To which Okey Ndibe responded ‘well, sometimes life is unsparing for all of us ... and sometimes you have a string of bad luck’. That was Ike – even his decision to marry Queen B (his African American wife who eventually enables him to get that ever elusive green card) was not ideal as she was extremely condescending to him.

Here, Okey Ndibe raises the issue of a colleague who read the book and wondered why he wrote such a deplorable African American female character. As Ndibe explains, Queen B had an insatiable sexual appetite and would want sex from Ike as soon as he got home - even if he had pulled an all night shift - and would refer to Ike as Zulu and accuse him of sleeping around. Ndibe says Queen B was not representative of all African American women, but just a specific kind of woman. She was also there to give a sense of the kind of choices that immigrants make, especially if you are desperate for a green card. You do not have the luxury of courting a professional woman of the same standing (e.g. Masters degree, great job) for a couple of years before proposing as asking her to marry you straight up, just won’t work (I know it would not for me).

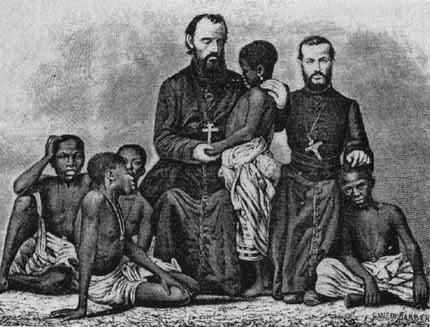

European Missionaries in Africa

Following this, I asked Okey Ndibe if he could give a reading from his book and he in turn invited the audience to read with him for an ‘orchestral reading’. He chose a section of the story where we go back in time to Reverend Walter Stanton (a European missionary sent to convert the ‘natives’). This particular section involved a a skeptical convert trying to understand why Stanton’s Christian God is invisible. So we took turns reading different sections.

His reading from Stanton made it possible for me to segue to my next question - Foreign Gods, Inc. also covers the battle between those who worship a Christian God and a traditional god and I wanted to know if there was any difference between the European missionaries like Reverend Stanton and modern day Pentecostal pastors like Pastor Uka who are both trying to destroy Ngene. Well, for Ndibe there is a difference. Missionaries like Stanton are ‘driven by his conviction [and] believed in what he was doing’. Pastor Uka, on the other hand, ‘uses religion for his self enrichment’. It was also interesting to find out that Uka means church in Igbo.

Nigerian Pentecostal Church (Source: http://www.theforeignreport.com/2012/12/16/nigeria-churches-business-or-salvation/)

Running out of time and also wanting to give the audience space to ask questions, my final question was on Stanton and if he was a precautionary tale for Ike (and really anyone who attempts to steal Ngene). As Ndibe states, this is what happens if you try and go against our war god. Finally, I asked if Stanton’s overall demise - the decomposition of his body, his disappearance into the river was really as a result of Ngene or him just being a European in the ‘harsh’ tropical climate. Ndibe responds by saying he ‘takes the spiritual dimension of gods seriously’. Ngene has an essence – the river - but Ngene was also made real by its powerful stench. And with that I opened up the questions to the floor.

Thankfully, it was not all over a, along with the Africa in Words team and a few others, we went on to have further discussions.There the conversation continued and it ranged from America’s obsession with American football and his UK tour to Arrows of Rain being republished in January 2015 (Ndibe shared with us his uncorrected proof, which he was currently looking through for typos).

The highlight (and there were many) of my evening though would have to be listening in awe as literary scholars discussed Achebe’s Things Fall Apart. I felt like I was invited into this space that I just needed to cherish. So like the ever-learning student I am, I sat in silence and absorbed their discussion and took in my surroundings – a loud student bar at the University of Sussex with Okey Ndibe and the awesome contributors from Africa in Words discussing whether Okonkwo was a man of thought or a man of action and if he was truly smart or accidentally smart. It was to use the words of Okey Ndibe’s editor after reading Foreign Gods, Inc., ‘captivating and fascinating’.

I felt so honoured and blessed to be in such a space, so thank you to Africa in Words for thinking of me to host this Q&A session and thank you to Okey Ndibe for graciously answering my questions. There were many more I had, like Mark Gruels and him being desensitised when it comes to religion, the commodification of traditional gods in the West, what Okey Ndibe was currently reading and new African writers he might recommend.