I’m not sure how I’ve managed to live in New Jersey eight years without discovering the Old Book Shop in Morristown. Used books represent the opportunity to find things otherwise hidden away, even often from the all-seeing internet. That’s why I visit book sales at any opportunity, and haunt used bookstores. The Cranbury Bookworm, never easy to reach, was denuded of its glory by a greedy landlord and has only a few shelves remaining in a much diminished location. The Montclair Book Center takes a concerted bit of driving from here, but I always enjoy it when I go. Over the weekend, however, the Old Book Shop was my destination. Although it’s not a large space, the books on display are reasonably priced and represent intelligent collecting. I found a book or two on my wish list there, and many more that, were I in a more lucrative line of work, would have come home with me.

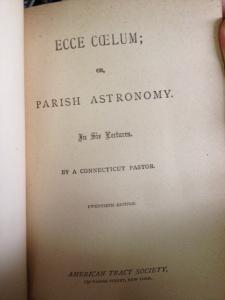

One book my daughter found in the science section, Ecce Coelum; or Parish Astronomy, by a Connecticut Pastor, was clearly from the days when science and religion got along better together. A little research revealed the author as Enoch Fitch Burr. What really caught my eye was the dedication, “lectures on astronomy in the interest of religion.” I’m not sure how I managed to leave that book behind, in retrospect. As a layman both in science in religion terms, I have had lifelong interests in both. It’s only been within the last couple of decades that I’ve noticed a growing tension between the siblings. Like all childhood fights, it is a contested matter of who started it. It does trace its roots back to Galileo and Bruno, but more recently to the Creationists and their never-ending campaigns to have their religion christened science. Back when Ecce Coelum was written, science and religion had much to learn from one another.

Now they no longer speak. Those who believe all answers lie in material explanations treat religion as a mental disease. The conservative religionists call the scientists atheists, as if that were still an insult. Name calling and bad feelings, I don’t believe, will ever lead to the truth. The science of today will eventually find its way into the used bookstores of tomorrow. Religion books have long lined these shelves, reminding me of the day when she was the queen of sciences. She’s often treated as the jester these days. What scientist now declares, “behold the heavens!”? We might actually benefit to a great degree if both the empirical and the ecclesiastical would behold their world with a little more wonder. And tomorrow’s readers will puzzle at our strange hardness of heart.