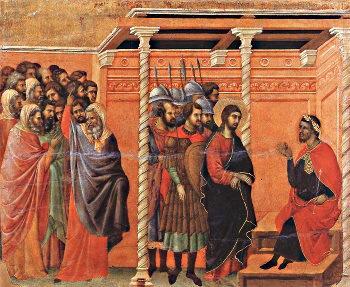

Pilate: “I Find no Fault in this Man”

[courtesy Google Images]

I’m not alleging that the following comments are correct or even consistent. I’m only saying that they cross my mind as interesting questions or possibilities.

Luke 23:1-2 “And the whole multitude of them arose, and led him unto Pilate. And they began to accuse him, saying, We found this fellow perverting the nation, and forbidding to give tribute to Caesar, saying that he himself is Christ a King.”

.

Note that “a” is an indefinite article. It signifies one of many who are otherwise similar or even identical.

According to the King James version of the Bible, the multitude accused the Messiah of claiming to be “a King,” that is to say, “a sovereign”—one of several, perhaps many, but not the only “King”/sovereign.

Luke 23:3 “And Pilate asked him, saying, Art thou the King of the Jews? And he answered him and said, Thou sayest it.”

.

Note that “the” is a definite article used to describe one who is in some way unique. He is “the” one and only. There is no other of the same classification.

Again, note that according to the KJV, unlike the Messiah’s accusers, Pilate did not ask the Messiah if he was “a King” or ”a sovereign”—meaning one “king” out of several “kings”/”sovereigns”.

Instead, the judge Pilate asked if the Messiah claimed to be “the” (singular, definite, one and only) “King of the Jews”.

In modern courts, if the Messiah denied having said that he was “the King of the Jews,” he might’ve created a controversy with the accusers and/or the judge and thereby given the court subject matter. Today, such denial and resulting controversy might’ve been achieved by a defendant simply declaring himself to be “not guilty” of the allegations against him.

On the other hand, if the Messiah admitted that he had expressly claimed to be “the King of the Jews” in a modern court, he might’ve provided a second witness (out of the mouths of two or three shall a thing be established) to support the multitude’s accusations. Alternatively, the defendant’s admission in open court could be construed as a confession in open court the allegations against him.

I’m not saying that some of the principles and procedures that might apply in modern courts also applied in Pilate’s court, twenty centuries ago. But I am considering that possibility.

What would happen in a modern court, if a defendant neither admits nor denies–somewhat like a nolo contendre/no contest plea– but instead says “Thou” [the judge] “sayest it” and/or “So you [the judge] say”. I wonder if the court would still have a legitimate charge against the defendant.

If the defendant didn’t deny his guilt by saying “not guilty,” would there be a controversy for the court to resolves?

If the defendant didn’t confess his guilty by saying “guilty as charged,” there might not be a second witness needed (in my opinion) to satisfy the requirements of probable cause to proceed to judgment.

I wonder if a judge in a judicial court has authority to start the trial (usually, only a sentencing hearing) until some actual witness (the cop, the injured party, the plaintiff or even the defendant) has introduced sworn evidence or allegation against the defendant. Most people assume that the plaintiff’s petition or prosecutor’s complaint provide the initial “sworn” evidence against the defendant. That may be true, but I wonder if a mere affidavit is enough to invoke the court’s jurisdiction to proceed. Does the court also need a confession from the defendant or a denial to create a controversy?

Because the judge was not a witness to the alleged offense, the judge in a judicial court shouldn’t be able to introduce evidence, make statements or perhaps even ask questions until after some sort of evidence has been introduced under oath into the court’s record.

I’ve heard or at least one defendant who, when asked how he pled to the charges, asked “What charges?” The judge said “The charges on the traffic ticket.” The accused said “No traffic ticket has yet been introduced into evidence.” The judge allegedly dismissed the case.

One unconfirmed case is nothing to rely on. Still, the story might make you think a bit.

I wonder if the judge in a judicial court should even be allowed to ask questions like “How do you plead?” until after some sworn evidence of an allegation against the defendant has been introduced into the court. By itself, is the cop’s traffic ticket sufficient to start a real trial? Or must the cop first be sworn in, take the stand, introduce the traffic ticket into evidence and then testify to validity of the facts reported on that ticket?

Should a judge be allowed to ask questions about an alleged traffic offense before the traffic ticket or traffic officer’s allegations have been introduced under oath into the case file?

More than likely, if the court is administrative rather than judicial, the court can probably do almost anything it pleases-including introducing its own evidence, making statements or asking questions based on evidence or allegations not yet introduced into the record.

• Remotely, it’s possible that when the Messiah responded to the judge Pilate’s question (“Art thou the King of the Jews?” by saying “Thou sayest it,” the Messiah converted the Judge into a witness. I.e., insofar as the judge “sayest” that the Messiah was “the King of the Jews,” the judge might be deemed a witness. If the judge were converted into the status of a witness, could he continue in the capacity of a judge?

Luke 23:4 “Then said Pilate to the chief priests and to the people, I find no fault in this man.”

.

Fascinating. Whatever the explanation, it appears that by neither admitting nor denying that he’d ever claimed to have been “the King of the Jews” and Messiah caused the court to drop the case and/or essentially find him innocent.

Luke 23:5 “And they were the more fierce, saying, He stirreth up the people, teaching throughout all Jewry, beginning from Galilee to this place.”

.

The multitude of accusers became more “fierce” in their demands that the Messiah be tried. Pilate was caught between being “politically correct” (following the demands of the multitude) and being technically “legal” (not prosecuting a man in whom he’d expressly “found no fault”

However, when he heard that the Messiah had started his alleged offenses in Galliee, Pilate saw his chance to dump the case.

Luke 23:6-7 “When Pilate heard of Galilee, he asked whether the man were a Galilaean. And as soon as he knew that he belonged unto Herod’s jurisdiction, he sent him to Herod, who himself also was at Jerusalem at that time.”

.

I’m not sure what the word “unto” (the Messiah “belonged unto Herod’s jurisdiction”) meant when the KJV was written as compared to what it means today. Did the Messiah “belong to” the Galilaean jurisdiction as property because he’d been born there? Or did the Messiah “belong in” the Galilaean jurisdiction because that was the first place where he’d allegedly committed his offenses?

If the Messiah was born in the Bethlehem of Galilee, he was a “Galilaean”. Herod, not Pilate, had jurisdiction/authority over Galilee and Galilaeans. If the Messiah had first committed his alleged offenses in Galilee, then Herod should be the first to try him.

Pilate “found no fault” in the Messiah and therefore should’ve released him. However, the “multitude” wanted the Messiah convicted and Pilate didn’t want to antagonize the crowd. Therefore, Pilate did the “politically correct” thing: Relying on claims that the Messiah was a Galilean and/or committed his first offenses in Galilee, Pilate had avoided his duty to free an innocent man or to convict an innocent man on the say-so of the “multitude”. Pilate was a man without moral conviction. So, he wriggled off the hook. At least temporarily.

And yet, as the Bible would later show, Pilate (who’d already said “I find no fault in” the Messiah) was seemingly chosen (perhaps even condemned) by God to issue the ultimate verdict against the Messiah. What is the implication of Pilate (who later wanted to “wash his hands” of responsibility for the Messiah’s conviction and crucifixion) being called by God to reach that verdict? Was God implicitly saying that none of us can escape liability for our moral and legal obligations to do justice? Must we all be compelled to judge only the guilty to be guilty and only the innocent to be innocent?