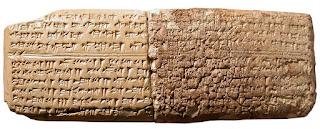

I got to thinking that as this is a written piece then how do musicians read what is on the pages of their scores. And then how did the system of notes and bars etc originate. However, when I got to looking at the history I found that as a non-musician a lot of the information was beyond me so I decided to pick out some of the highlights which intrigued me.It’s known from designs on pottery and artefacts that the use of music has been part of humanity from its earliest times in both religious and secular activities. Possibly as long ago as 60,000 years. But the first sign of some form of notation has been found in what is called the Hurrian Hymns, a collection of music inscribed in cuneiform on clay tablets excavated from the city of Ugarit in Mesopotamia (no comment) dating to approximately 1400 BCE.

Philolaus and Pythagoras

In 600 BCE Pythagoras, while walking past a blacksmith’s workshop, was intrigued that the sounds made by the smiths’ hammers sound like tuneful musical notes. He was a musician as well as mathematician so he went home does some calculations and worked out the mathematical proportions governing the notes of the music scale. He discovered that two notes which make an interval of an octave always have a ratio of 2:1. A perfect fifth is made with the ratio of 3:2, and a perfect 4th is 4:3. Combinations of these intervals then create the other notes which make up the major scale.The scholar and music theorist Isidore of Seville, while writing in the early 7th century, considered that ‘unless sounds are held by the memory of man, they perish, because they cannot be written down.’ By the middle of the 9th century, however, a form of notation began to develop in monasteries in Europe as a mnemonic device for Gregorian chant, using symbols known as neumes; the earliest surviving musical notation of this type is in the Musica Disciplina of Aurelian of R茅么me, from about 850 CE.

Guido d'Arezzo, the musical monk

The founder of what is now considered the standard music staff was Guido d'Arezzo, an Italian Benedictine monk who lived from about 991 until after 1033. The syllables Guido d'Arrezo chose to use in the system he developed as an aid in the teaching of sight-singing were based on a hymn to Saint John the Baptist, which begins Ut Queant Laxis and was written by the Lombard historian Paul the Deacon.1. Ut queant laxis2. resonare fibris,

3. Mira gestorum

4. famuli tuorum,

5. Solve polluti

6. labii reatum,

7. Sancte Iohannes.And what did that become? Answer below.

By the 12th Century, we find many manuscripts with a five-line stave that we recognize today. However, the system of musical notation was not quite complete. There was still no indication of how long a note should last. Franco of Cologne was the first person to address this, creating a series of square- and diamond-shaped notes with no stems. This system was later adapted by Philippe de Vitry who created symbols that would not be entirely unrecognisable today.The notes were named, with the Maxima being the longest, however as music has a tendency to speed up, it was equivalent to our modern semibreve, four beats.Bar lines were added in the 17th Century. Now musicians could really write down musical ideas. This lead to more complex compositions and began shifting the music of the time from Baroque to Classical music. Around this time, notes also became more rounded, forming the symbols we know today.There is a mind numbing amount of poems about music so I thought this might be more suitable and is the answer to my question. I bet you can’t help singing along.

The Sound of Music

Do-Re-MiLet's start at the very beginning

A very good place to start

When you read you begin with A-be-see

When you sing you begin with do-re-mi

Do-re-mi, do-re-mi

The first three notes just happen to be

Do-re-mi, do-re-mi

Do-re-mi-fa-so-la-ti…

Let's see if I can make it easier

Doe, a deer, a female deer

Ray, a drop of golden sun

Me, a name I call myself

Far, a long, long way to run

Sew, a needle pulling thread

La, a note to follow Sew

Tea, a drink with jam and bread

That will bring us back to Do (oh-oh-oh)

Do-re-mi-fa-so-la-ti-do

So-do!

Oscar II Hammerstein, Richard Rodgers

Thanks for reading. Happy New Year, Terry Q.

Email ThisBlogThis!Share to XShare to Facebook