“It isn’t so astonishing, the number of things that I can

remember, as the number of things I can remember that aren’t so.”

Mark Twain

On July 16th, 1996, the bodies of four innocent people were discovered in a furniture store in Winona, Mississippi. Each victim had been murdered execution style—one or two bullets to the back of the head. The presence of live ammunition on the floor suggested that one of the killers was using a 380 pistol that jammed repeatedly.

Nine days later, July 25, 1996, the bodies of two innocent people were discovered in a pawn shop in Birmingham, Alabama. Each victim had been murdered execution style—one or two bullets to the back of the head. A surveillance camera revealed that the killer was wielding a 380 pistol that jammed repeatedly.

Winona, Mississippi lies three hours west of Birmingham on Highway 82. Steven McKenzie, the driver of the getaway car in the pawn shop murders, was arrested on August 1 in his hometown of Boston, Massachusetts. The killer, Marcus Presley (16) and his accomplice, Lasamuel Gamble (18) were arrested in Norfolk, Virginia on August 9, 1996 after two weeks on the run. That same day, Horace Wayne Miller, a lieutenant with the Mississippi Highway patrol, asked Norfolk officials to keep him apprised of their investigation.

Two weeks later, a picture of Marcus Presley, the shooter in the Birmingham murders, was included in a photo array shown to a witness in the Winona, Mississippi case.

On November 16, 2015, Marcus Presley signed an affidavit claiming that Lasamuel Gamble and Steven McKenzie (the driver of the getaway car) had been in Mississippi the day of the Winona murders and had returned with several hundred dollars in their pockets after claiming to have “hit a lick” (committed a crime).

A shoeprint in a pool of blood found in the Winona furniture store was found to be from a Grant Hill Fila shoe—the footwear Gamble, McKenzie (and just about every other young man in America) was wearing while in Mississippi.

Can Marcus Presley’s affidavit be trusted? Yes and no.

Courtroom testimony shows that Presley was the shooter in the pawn shop murders in Birmingham even though, prior to being shown video of the crime, he insisted that Gamble had been the gunman. If Gamble and McKenzie were in Mississippi the day of the Winona murders it’s likely that Presley was with them.

Between June 19th, 1996 and June 30th of that year, Presley was involved in five robberies at gunpoint. In the course of these crimes, one employee was shot in the leg and another in the back (both survived) and Presley was the shooter in both cases. Presley and Gamble did four of the June heists together and one crime was perpetrated by Presley alone. Although Presley was only sixteen, he seems to have been the driving force behind these crimes. Gamble never discharged his weapon.

Presley and Gamble had developed a simple modus operandi. Store employees were threatened with death and forced to lie on the floor. While Presley drove the action, Gamble kept his gun trained on the scene in case anyone tried to flee. After the second stick up, the two men argued about whether they should have killed the witness.

Evidence suggests that Marcus Presley was a psychopath who enjoyed random violence for its own sake.

Presley and Gamble made three runs to Boston during the summer of 1996: once after their June crime spree, once after the pawn shop murders and once immediately after the furniture store murders in Winona. Their pattern was to spend a week or so lying low before going on another rampage. The two men had family in both Boston and Norfolk.

If you are have been following the quadruple homicide in Winona, Mississippi, the Presley-Gamble connection may surprise you. In June of 2010, Curtis Flowers was sentenced to death for the murder of Bertha Tardy (the owner of the furniture store) Carmen Rigby (the business manager) and Bobo Stewart and Robert Golden (two recent hires). Flowers had worked three days at the Tardy furniture store but failed to return to work after the July 4th holiday.

District Attorney Doug Evans argues that Flowers, enraged with losing his job, stole a gun out of a parked car at the Angelica garment factory, cooled his heels at home for an hour or so, then marched to the furniture store with murder in his eye, did the foul deed, and raced home.

But how could a single person (especially a man like Curtis Flowers) dispatch four victims with a bullet to the back of the head? The crime had a random and senseless quality to it. It takes no imagination at all to imagine Marcus Presley committing a crime like that–we have the video from the pawn shop.

Curtis Flowers was raised in a loving home by a gospel-singing father and a mother known for her culinary and entrepreneurial abilities. Marcus Presley and Lasamuel Gamble weren’t raised at all. Both men bounced from one traumatic living arrangement to another with no respite. Whoever killed the four victims in Winona was beset by demons. Curtis Flowers, as any prison guard who has ever worked with him can tell you, has no demons.

So why didn’t DA Doug Evans even consider the Presley-Gamble connection?

By the time Presley and Gamble were arrested, Evans wasn’t interested in alternative scenarios; he knew Curtis was the killer.

Then why haven’t the defense attorneys who have represented Mr. Flowers through six trials present Presley and Gamble as an alternative theory of the crime?

Because Mr. Evans didn’t tell them about the Alabama connection. It was his legal obligation, but it’s easy to see why he didn’t. Evans didn’t want jurors comparing his tortured theory with a simple and sensible alternative.

But here’s the thing people can’t get past: if Curtis Flowers didn’t do it, why are so many eye witnesses convinced that they saw him around the Angelica parking lot and the scene of the crime?

Patricia Sullivan-Odom claims she saw Flowers leaving his home at around 7:50 heading, so she thought, in the direction of the Angelica furniture factory. Patricia’s brother, Odell, has testified that Curtis confessed to the crime while the two men were locked up together.

James Edward Kennedy insists that he saw Curtis walking towards the Angelica Clothing Factory at 7:15 that morning.

Katherine Snow testifies that she saw Flowers leaning up against Doyle Simpson’s car at about 7:15 a.m.

Edward Lee McChristian says he saw Curtis on Academy Street, heading home, between 7:30 and 8:00 that morning.

Mary Jeannette Flemming insists she saw Curtis Flowers walking in the general direction of the Tardy furniture store at about 9:05 am.

Beneva Henry saw Flowers walking in the direction of downtown Winona somewhere between 9:00 and 9:30 that morning.

Porky Collins says he saw Curtis Flowers and another black men having an intense argument in front of the Tardy furniture store at about 10:00 that morning.

Finally, Clemmie Flemming has testified that she saw Petitioner fleeing the crime scene shortly after 10:00 a.m.

And this wealth of eye witness testimony explains why jurors have been willing, even eager to convict Curtis Flowers in four of the six trials that have flowed from the awful events of July 16, 1996. One or two of them might be wrong, and some of them might even be lying, but the cumulative effect of so much testimony has been decisive. Even the Mississippi Supreme Court is impressed.

Of course, the gross discrepancies between the various witness statements have been frequently mentioned. Witnesses have Curtis wearing a jogging outfit, Sunday-go-to-meeting finery and everything in between. But jurors know memory isn’t perfect. All the witnesses say they saw Curtis Flowers, and that’s all that matters.

The state’s stable of witnesses has been able to overcome another gaping hole in the state’s evidence. According to the state’s theory of the crime, the suspect stole a gun locked in the glove compartment of Doyle Simpson’s brown Buick. This quirky detail entered the picture because, the very morning of the crime, the gun’s owner was telling anyone who wanted to hear that his gun was missing.

But the state’s witnesses insist the gun was stolen between 7:30 and 8:00 o’clock. Simpson has repeatedly testified that when he checked on his car at 10:30 the glove compartment was still closed. Half an hour later, at 11:00 am, Doyle saw the glove box hanging open and his gun was gone.

Doyle Simpson is the only source of the stolen gun theory. If his testimony is credible, the gun wasn’t stolen until after 10:30 which renders the testimony of the four witnesses who saw Curtis hanging around between 7:15 and 7:30 irrelevant. At 10:30, the time Simpson says his gun was still locked up safe and sound, the murders had already been committed.

I have previously argued that most of the state’s witnesses in the Flowers case are lying. A combination of fuzzy memory (witnesses were first interviewed between a month and nine months after the crime), promises of a $30,000 reward and intimidation tactics produced witness testimony. Threats of punishment have kept witnesses repeating the same story for two decades.

I was half right.

The credibility of the state’s two star witnesses has evaporated since the last trial in 2010. Patricia Sullivan-Odom, the woman who says she saw Curtis leaving his home at suspicious times, was under federal indictment for tax fraud when she last testified and Doug Evans knew it. Patricia Hallmon lied to her customers and to the IRS in order to line her own pockets. If there is a seventh trial, she won’t be testifying.

Then Patricia’s brother, Odell (the jailhouse snitch who says Curtis confessed to him) eventually got out of prison, fell out with his girlfriend and his drug dealing friends, and gunned down three people in cold blood. A fourth victims of Odell’s rampage will live out his days in a wheelchair.

Odell’s days as a state’s witness are over.

But I am no longer convinced that the remaining witnesses are lying, but most of what they remember didn’t happen.

The prosecution of criminals is largely dependent on eye witness testimony. Few crimes generate meaningful physical evidence proving that a particular suspect is guilty. One study found that only 10% of criminal cases involved meaningful forensic evidence and, even in these cases, that evidence was submitted for expert analysis only half the time.

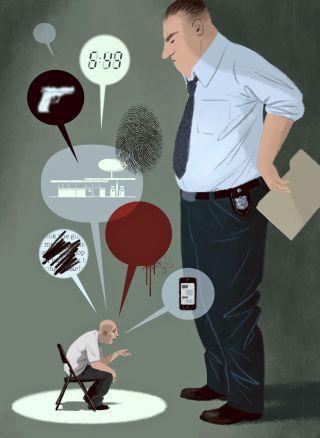

The prosecution of Curtis Flowers is typical in this respect. No meaningful fingerprint or DNA evidence was recovered from the crime scene and the murder weapon was never found. Doug Evans and associates did their best to wring apparent meaning out of the few scraps of physical evidence at their disposal, but the case against Mr. Flowers stands or falls on eye witness testimony.

Because witnesses are critical to gaining convictions, the Supreme Court has repeatedly ruled that, in the process of interviewing suspects and potential witnesses, investigators can lie about the basic facts of the case, make false promises, pretend they have an airtight case when they don’t, or even deprive interviewees of sleep and food for long periods of time. These tactics would be considered reprehensible in most settings, but if suspects don’t sign confessions and witnesses don’t cooperate perpetrators walk free.

The fact that the eye witnesses didn’t finger Curtis Flowers until between a month and nine months after the crime isn’t considered problematic because, in the criminal justice system, memory is generally conceived as a series of photographs, or as a video. With sufficient reflection, it is believed, essentially accurate memories can be uploaded from the brain’s memory banks.

No one expects witness memory to be perfect, of course. The fact that the various witnesses in the Flowers case remember him wearing entirely different outfits is what we would expect. Memory’s video may be a bit grainy, but it’s good enough.

But memory doesn’t work that way. Elizabeth Loftus, the world’s leading authority on the human memory, says that memory has more in common with imagination than photography. “Memory is constructed and reconstructed,” she says. “It’s more like a Wikipedia page — you can go change it, but so can other people.” (Her terrific TED talk on the subject that will quickly bring you up to speed.)

“When we recall our own memories,” Christopher Chabris and Daniel Simons wrote in a 2014 NYT op-ed, “we are not extracting a perfect record of our experiences and playing it back verbatim . . . We are effectively whispering a message from our past to our present, reconstructing it on the fly each time.”

In The Memory Illusion: Remembering, Forgetting and the Science of False Memory, Julia Shaw describes a 2015 study conducted as part of her doctoral dissertation at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan. First, Shaw and her associates called up the parents of several dozen ordinary university students and asked them to recall a real event from their child’s adolescent years. Subjects were asked if they remembered the event and almost all of them did. Then things got interesting.

Subjects were told (falsely) that their parents had also described an upsetting incident involving behavior so troubling that the police were involved. Initially, none of the study participants could recall anything of that sort, but they were assured that painful memories could be retrieved with sufficient reflection. Subjects were asked to go home and give the matter more thought.

In the second interview, participants were told that if they imagine what the painful incident from our past might have been like, genuine memories may be triggered.

Shaw based her experiment on the Reid technique, a method for obtaining eye witness testimony and confessions that is employed almost universally in the United States and Canada. This new approach was developed in the late 1950s and early 1960s by John Reid, a former Chicago cop, as a humane alternative to old “third degree”, a polite synonym for torture. Prior to Reid, suspects were routinely beaten, scalded and electrocuted into compliance.

Reid thought he could do better. During an initial interview with a suspect, Reid looked for non-verbal indications of guilt. Nervous suspects were considered guilty, especially if they picked at invisible lint on their clothes, looked down or shifted their eyes to the left. There was no scientific basis for these supposed guilt-indicators, it was all based on Reid’s “professional experience”.

If this initial interview indicated guilt, the gloves came off. The investigator re-entered the room, standing over the suspect to project dominance and waving a case file supposedly brimming with air tight proof of guilt. Protestations of innocence, attempted explanations, and requests to look at the file are batted away as the interrogator lays out his theory of the crime as revealed truth. “You’re time to talk will come later,” suspects are told, “now you’re going to listen.”

Once the suspect stops asserting innocence, the investigator’s voice softens and the “minimization” process begins. The legal consequences of the alleged crime are set to one side while the moral implications are minimized. The 1962 edition of Reid’s textbook featured thousands of proposed minimizations, including this gem:

Joe, no woman should be on the street alone at night looking as sexy as she did. Even here today, she’s got on a low-cut dress that makes visible damn near all of her breasts. That’s wrong! It’s too much temptation for any normal man. If she hadn’t gone around dressed like that you wouldn’t be in this room now.

None of this stands up to scientific scrutiny.

Saul Kassin, Distinguished Professor of Psychology at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City, conducted a series of experiments in which randomly selected college students and trained police investigators were shown videos of actual inmates telling stories–half true, half false. Participants were asked to detect who was lying. Kassin found the officers, who focused on non-verbal clues, did less well than the students, but were far more confident in their conclusions.

There may be no scientific support for the Reid technique, but whether used on suspects or potential witnesses, it gets results.

Julia Shaw’s 2015 experiment employed procedures suggested by the Reid technique. Stephen Porter, Shaw’s Ph.D. supervisor, says they were expecting a modest (though statistically significant) results from their manipulations and were appalled by the actual results. By the conclusion of the third session, 70% of subjects were recalling hideous, self-incriminating events complete with smells, emotional reactions and detailed physical descriptions. Once these false memories had taken hold, moreover, it was often difficult to convince test subjects that they had been duped.

False memories feel just as real as true memories. That’s why the confidence of the witness is a meaningless measure of veracity. Here’s Julia Shaw’s takeaway:

It is crucial that the justice system becomes aware of overconfidence factors, memory illusions and the problems we have with identification, since these can lead to atrocious situations where we sometimes build cases based on nothing but air.

The Innocence Project reported in 2015 that, of the 325 cases in which defendants were exonerated by incontrovertible DNA evidence, 235 involved mistaken eyewitness testimony and a full 25% involved false confessions.

In his book Searching for Memory, Daniel Schacter recounts a well-known story about Ronald Reagan:

In the 1980 presidential campaign, Ronald Reagan repeatedly told a heartbreaking story of a World War II bomber pilot who ordered his crew to bail out after his plane had been seriously damaged by an enemy hit. His young belly gunner was wounded so seriously that he was unable to evacuate the bomber. Reagan could barely hold back his tears as he uttered the pilot’s heroic response: “Never mind. We’ll ride it down together.” The press soon realized that this story was an almost exact duplicate of a scene in the 1944 film A Wing and a Prayer. Reagan had apparently retained the facts but forgotten their source.

When Hillary Clinton or Brian Williams “remember” being under enemy fire, they aren’t necessarily fibbing to make themselves look good; in all likelihood they remember the bullets whirring past their ears.

Although we are constantly remembering things that didn’t happen, the consequences are usually harmless. But when a low-status individual is hauled down to the police station and subjected to a variation on the Reid technique, memory can easily be contaminated. Witnesses who initially have nothing to offer eventually “remember” exactly what investigators are looking for.

Consider the case of Katherine Snow, a key witness in the Curtis Flowers case. Unlike most of the state’s witnesses, Snow was questioned shortly after the yellow tape went up around the Tardy furniture store. She told investigators that, when she arrived at work around 7:15 am, she saw a man leaning up against Doyle Simpson’s car. He was chubby, short (around five-foot-six) and wearing a cap.

Once investigators (following the Reid technique) had established that Curtis Flowers was guilty, they no longer had to worry about Curtis Presley and LaSamuel Gamble. They also knew the man Snow claimed to have seen had to be at least four inches taller and slim, not fat. That is, the man had to be Curtis Flowers. On the witness stand, Snow says that police officers carried her down to the station repeatedly until she “remembered” that the man she saw was Curtis, a man she knew well from their joint participation in gospel singing concerts.

At the most recent trial in 2015, Katherine Snow admitted that her encounters with the police unnerved her. Julia Shaw emphasizes that memory is easily contaminated when there is a significant status imbalance between the person asking the questions and the person providing the answers.

I have always assumed, therefore that Snow, driven to distraction by these repeated inquisitions, eventually broke down and told investigators what they wanted to hear. But if leading authorities like Loftus, Shaw and Kassian are right, it is more likely that when Katherine Snow “remembers” the morning of July 16, 1996, she actually sees Curtis Flowers leaning up against Doyle Simpson’s car. Every time she remembered the event, the man looked a little more like Curtis.

Another group of state witnesses wasn’t approached by police until the murders at the furniture store were distant memory. Seven months after the crime, for instance, Mary Jeannette Flemming was picked up at her job at McDonalds and whisked away to the police station. Records showed she had visited the body shop across the alley from the Tardy furniture store on the morning of the crime.

Flemming says that Flowers (moments away from committing the most heinous crime in Winona history) grinned and said, “Hi, good looking.”

What are the chances that Flemming actually saw Flowers on the morning in question? By February, 1997, everyone on the poor side of Winona knew about the $30,000 reward being offered. It was one of those legal lies the authorities are allowed to tell—no one has received a dime for their testimony in this case—but Mary Jeannette likely believed the promise.

Has Mary Jeannette Flemming been lying on the witness stand? Probably not. She likely remembered seeing someone on the street that morning and, as police officers plied her with questions, the face of that person took on the aspect of Curtis Flowers. That’s the way false memory works.

In their groundbreaking The Science of False Memory, Charles Brainerd and Valerie Reyna show that when we process a past event we store and retrieve ‘verbatim’ memory (what the scene looked like) and ‘gist’ memory (the meaning we assign to the event) separately. For instance, we can sometimes remember a person’s name without remembering what they look like, or vice versa. Gist memory (what the event means to us) is usually stronger than verbatim memory (what it looked like).

In all likelihood, Curtis Flowers once had an encounter with Mary Jeannette Flemming in which he complimented her on her appearance. If you know Curtis, “hi, good looking” is exactly the sort of thing he would say to a woman. Within thirty seconds of such an encounter, a gist memory will either be “stamped” in the memory or forever forgotten. We forget the vast majority of our experiences because they carry no significance and we have bigger fish to fry. But even if Ms. Flemming remembered the gist of her encounter with Curtis (the good feeling that accompanies a compliment) the verbatim memory trace (the street outside the body shop) could either be lost or the gist memory trace could, especially at a remove of seven months, be attached to a different verbatim trace.

This is why we often remember what was said (because we attach significance to it) but attach it erroneously to a separate verbatim trace. You might remember a conversation over a few beers (gist memory) but recall that it happened at the wrong bar (verbatim memory). False memories are created when gist memory is associated with the wrong verbatim memory. This is why memory is so easily distorted. We are always confusing gist and verbatim memory traces without realizing we are doing it.

Forgetting is an important brain function. If we didn’t slough off the inconsequential events of the average day we wouldn’t be able to concentrate on the task at hand. What are the chances, therefore, that Mary Jeannette Flemming was able to recall her encounter with Curtis Flowers seven months after the event? Asked repeatedly if she was sure it wasn’t Curtis Flowers she saw that morning, Ms. Flemming was being asked to re-imagine the event, which is precisely how Julia Shaw got college students to conjure false memories.

And yet, when the justices of the Mississippi Supreme Court read court documents from the Flowers case they take her testimony at face value. A huge and widening gap exists between researchers on the cutting edge of memory science (who see memory as infinitely vulnerable to distortion) and functionaries within the criminal justice system (who think of memories as retrieved photographs).

Porky Collins, the man who says he saw Curtis Flowers arguing with another black man twenty feet from the crime scene, is a unique case. Collins presented himself to investigators the day of the crime and was confident from the drop that, at approximately 10 am the morning of the crime, he saw a man sitting inside a car in front of Tardy furniture arguing with another man who was standing at the front of the car. When he made the block and passed the car on the other side of the Boulevard, the two men were walking toward the crime scene.

But Collins wasn’t asked to identify these two men until over a month had elapsed.

As Breynard and Reyna remind us in The Science of False Memory,

When a substantial period of time elapses between the occurrence of a crime and suspect identifications, there are opportunities for witnesses to be exposed to additional information that points to specific suspects but that is not part of their original experience. Examples include conversations with other witnesses, media reports of the crime, and conversations with investigators.

Over a month after the crime, Collins (after speaking informally with investigators on several occasions) was shown a photo array including pictures of Marcus Presley (the shooter in the Birmingham pawn shop murders), Doyle Simpson and Curtis Flowers (the rest of the faces were fillers). Since the head of Curtis Flowers was half again as big as the heads in the other pictures, his photo naturally attracted Porky’s attention. As the witness’s finger lingered over the suspect’s photo, and helpful officer asked, “Do you know Curtis Flowers?”

In The Science of False Memory, Brainerd and Reyna demonstrate that verbatim face memory (the ability to identify a specific suspect) falls to near zero after eight days while gist facial memory (it was a black guy) often remains relatively strong.

When an eye witness is confronted with an identification test after a few days, innocent suspects who share salient categories of appearance with culprits will seem familiar (which supports false identification), but verbatim traces of incidental features that differentiate culprits from such suspects are no longer readily accessible.

A month after an event, the authors say, verbatim memory is normally gone and gist memory is getting weak. Porky Collins admits that he was driving past the scene and only caught a split-second glimpse of the man standing at the hood of the car. Moreover, cross-racial identifications (Collins was white) are notoriously problematic.

But there has never been any reason to doubt that Collins saw two black men arguing in front of the furniture store thirty minutes (at the very least) after the murders took place. These details were reported the day of the crime.

If Curtis Flowers walked to the furniture store and fled the crime scene on foot, why was he arguing with a man in a car? What were they arguing about? And why was Curtis walking toward the Tardy furniture store with this man? Where were they going? Neither the state nor defense counsel have ever asked these questions. Porky Collins’ testimony is entirely consistent with the Presley-Gamble hypothesis but can’t be squared with the state’s theory of the crime.

Finally, we come to Clemmie Flemming, a young woman who says she saw Curtis Flowers fleeing the scene of the crime at about the same time Porky Collins saw him walking toward the store with another man. Clemmie is clearly mistaken. The man who drove her that morning says they never saw Curtis Flowers and several members of her family insist that Clemmie was with them on that fateful morning. Finally, nine months elapsed between the crime and Clemmie’s statement.

Again, I have always assumed that Clemmie was lying. Witnesses have testified that she was offered a carrot (the forgiveness of her debt to Tardy furniture) and threatened with a stick (the threat that CPS would take her children is she refused to cooperate). Perhaps so, but that doesn’t mean that when Clemmie “remembers” the morning of the crime she doesn’t see Curtis Flowers sprinting from the scene like a track star. After telling the same story six times to six different juries, a false memory, as clear and detailed as a photograph, could easily have taken up residence in her mind.

Given what we know about memory, how hard would it have been to find seven or eight people who remembered seeing Curtis Flowers (or any other familiar face in the community) the morning of the crime? All they had to remember was seeing him pass by a certain place at a certain time. Think about it long enough (especially if the authorities are pressuring you and you actually believe there may be $30,000 in it for you) and the required memory will appear. This won’t happen to everybody the police talk to, but in the course of a year-long investigation, witnesses will emerge. If Judy Shaw can create self-incriminating memories in college students using the Reid technique, how easy would it be to infect the memories of low-status black witnesses on the poor side of town?

The crime makes a twisted kind of sense if we pin it on a couple of Birmingham psychopaths with a lust for drama, especially when we know they were in Mississippi at the time. But prosecutor Doug Evans never explored that option. In fact, he prevented defense counsel from investigating the Birmingham connection by illegally burying the Presley-Gamble evidence. Then he and his investigator, John Johnson, spent a year fabricating “evidence” that would convict an innocent man.

We aren’t dealing with a shocking anomaly here—this is business as usual for the criminal justice system. Most prosecutors wouldn’t lie and cheat as brazenly as Doug Evans, but simply by following best practices, investigators routinely plant and manipulate false testimony and even false confessions. That isn’t necessarily their intention, but that’s what they do.

Sp here’s the question. If the memory experts cited in this essay were asked to examine the Flowers case, how much confidence would they have in the state’s witnesses? To ask the question is to answer it. Unfortunately, most prosecutors and judges view memory science with grave suspicion and few defense attorneys use memory scientists as expert witnesses. If Curtis Flowers is ever going to get the justice he deserves, that will have to change