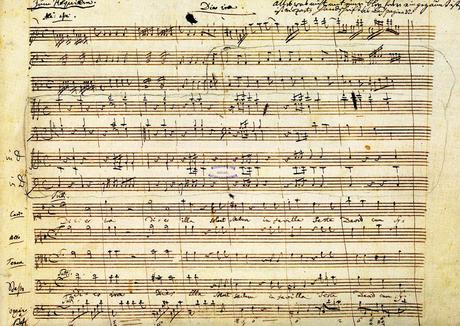

Mozart's Requiem is a work perhaps inevitably burdened with our expectations of it: that it should be Mozart's testament, or a consolation for his early death; that it should portentously reveal not only mysteries of humanity and the divine, but mysteries of Mozart, whom history has never quite succeeded in classifying. The musicians united for Thursday's performance gave it both vigor and nuance, as (I thought) more an invitation to contemplate mysteries than an anxiously proposed solution. The soloists, all very fine, worked admirably together in the graceful intertwining, echoing melodies of mourning and prayer. There were one or two moments where Dominique Labelle seemed to have trouble on a breath, but she sang with a wonderfully pure, warm tone. Kelley O'Connor's dark mezzo--focused, but sensual and rich in colors--provided a fascinating contrast. Joseph Kaiser sang with easy, elegant phrasing, and his bright tenor was admirably supple. Even, fluid sonority was contributed by Richard Paul Fink. The members of Musica Sacra--women positioned among the strings and woodwinds, men ranged behind the brass--contributed beautifully expressive choral work. In response to Fischer's cues, they varied the color of their sound to fit the text, an effect especially notable in the "Kyrie." Meditative pauses between movements were employed selectively and effectively by Fischer. In the final movements, reminiscences of earlier phrases and themes emerged clearly. After the final chord, Fischer's baton enforced silence long enough to be reflective rather than merely expectant. And then we stood, and Fischer motioned the orchestra and singers to their feet, and we shared our joy.

Mozart's Requiem is a work perhaps inevitably burdened with our expectations of it: that it should be Mozart's testament, or a consolation for his early death; that it should portentously reveal not only mysteries of humanity and the divine, but mysteries of Mozart, whom history has never quite succeeded in classifying. The musicians united for Thursday's performance gave it both vigor and nuance, as (I thought) more an invitation to contemplate mysteries than an anxiously proposed solution. The soloists, all very fine, worked admirably together in the graceful intertwining, echoing melodies of mourning and prayer. There were one or two moments where Dominique Labelle seemed to have trouble on a breath, but she sang with a wonderfully pure, warm tone. Kelley O'Connor's dark mezzo--focused, but sensual and rich in colors--provided a fascinating contrast. Joseph Kaiser sang with easy, elegant phrasing, and his bright tenor was admirably supple. Even, fluid sonority was contributed by Richard Paul Fink. The members of Musica Sacra--women positioned among the strings and woodwinds, men ranged behind the brass--contributed beautifully expressive choral work. In response to Fischer's cues, they varied the color of their sound to fit the text, an effect especially notable in the "Kyrie." Meditative pauses between movements were employed selectively and effectively by Fischer. In the final movements, reminiscences of earlier phrases and themes emerged clearly. After the final chord, Fischer's baton enforced silence long enough to be reflective rather than merely expectant. And then we stood, and Fischer motioned the orchestra and singers to their feet, and we shared our joy.

Culture Magazine

Mozart on Life and Death: Orchestra of St. Luke's at Carnegie Hall

By Singingscholar @singingscholar

Thursday night saw the Beloved Flatmate and me at Carnegie Hall for the last in a very satisfying series of subscription concerts. Following Beethoven's Missa Solemnis and Bach's Johannespassion, Thursday's concert showcased Mozart's Requiem, performed in its completed version, and paired with his Symphony No. 34 in C Major. This was my first time (hopefully the first of many) hearing the excellent Orchestra of St. Luke's live. The presence of Iván Fischer on the podium was another gift; his apparently boundless enthusiasm for the composer gives Mozart a welcome vitality and freshness. The Thirty-Fourth Symphony was joyous and graceful, with subtle changes in dynamics like shared merriment, exuberant fanfares, and interwoven musical themes like dancers in a brightly-lit room.

Mozart's Requiem is a work perhaps inevitably burdened with our expectations of it: that it should be Mozart's testament, or a consolation for his early death; that it should portentously reveal not only mysteries of humanity and the divine, but mysteries of Mozart, whom history has never quite succeeded in classifying. The musicians united for Thursday's performance gave it both vigor and nuance, as (I thought) more an invitation to contemplate mysteries than an anxiously proposed solution. The soloists, all very fine, worked admirably together in the graceful intertwining, echoing melodies of mourning and prayer. There were one or two moments where Dominique Labelle seemed to have trouble on a breath, but she sang with a wonderfully pure, warm tone. Kelley O'Connor's dark mezzo--focused, but sensual and rich in colors--provided a fascinating contrast. Joseph Kaiser sang with easy, elegant phrasing, and his bright tenor was admirably supple. Even, fluid sonority was contributed by Richard Paul Fink. The members of Musica Sacra--women positioned among the strings and woodwinds, men ranged behind the brass--contributed beautifully expressive choral work. In response to Fischer's cues, they varied the color of their sound to fit the text, an effect especially notable in the "Kyrie." Meditative pauses between movements were employed selectively and effectively by Fischer. In the final movements, reminiscences of earlier phrases and themes emerged clearly. After the final chord, Fischer's baton enforced silence long enough to be reflective rather than merely expectant. And then we stood, and Fischer motioned the orchestra and singers to their feet, and we shared our joy.

Mozart's Requiem is a work perhaps inevitably burdened with our expectations of it: that it should be Mozart's testament, or a consolation for his early death; that it should portentously reveal not only mysteries of humanity and the divine, but mysteries of Mozart, whom history has never quite succeeded in classifying. The musicians united for Thursday's performance gave it both vigor and nuance, as (I thought) more an invitation to contemplate mysteries than an anxiously proposed solution. The soloists, all very fine, worked admirably together in the graceful intertwining, echoing melodies of mourning and prayer. There were one or two moments where Dominique Labelle seemed to have trouble on a breath, but she sang with a wonderfully pure, warm tone. Kelley O'Connor's dark mezzo--focused, but sensual and rich in colors--provided a fascinating contrast. Joseph Kaiser sang with easy, elegant phrasing, and his bright tenor was admirably supple. Even, fluid sonority was contributed by Richard Paul Fink. The members of Musica Sacra--women positioned among the strings and woodwinds, men ranged behind the brass--contributed beautifully expressive choral work. In response to Fischer's cues, they varied the color of their sound to fit the text, an effect especially notable in the "Kyrie." Meditative pauses between movements were employed selectively and effectively by Fischer. In the final movements, reminiscences of earlier phrases and themes emerged clearly. After the final chord, Fischer's baton enforced silence long enough to be reflective rather than merely expectant. And then we stood, and Fischer motioned the orchestra and singers to their feet, and we shared our joy.

Mozart's Requiem is a work perhaps inevitably burdened with our expectations of it: that it should be Mozart's testament, or a consolation for his early death; that it should portentously reveal not only mysteries of humanity and the divine, but mysteries of Mozart, whom history has never quite succeeded in classifying. The musicians united for Thursday's performance gave it both vigor and nuance, as (I thought) more an invitation to contemplate mysteries than an anxiously proposed solution. The soloists, all very fine, worked admirably together in the graceful intertwining, echoing melodies of mourning and prayer. There were one or two moments where Dominique Labelle seemed to have trouble on a breath, but she sang with a wonderfully pure, warm tone. Kelley O'Connor's dark mezzo--focused, but sensual and rich in colors--provided a fascinating contrast. Joseph Kaiser sang with easy, elegant phrasing, and his bright tenor was admirably supple. Even, fluid sonority was contributed by Richard Paul Fink. The members of Musica Sacra--women positioned among the strings and woodwinds, men ranged behind the brass--contributed beautifully expressive choral work. In response to Fischer's cues, they varied the color of their sound to fit the text, an effect especially notable in the "Kyrie." Meditative pauses between movements were employed selectively and effectively by Fischer. In the final movements, reminiscences of earlier phrases and themes emerged clearly. After the final chord, Fischer's baton enforced silence long enough to be reflective rather than merely expectant. And then we stood, and Fischer motioned the orchestra and singers to their feet, and we shared our joy.

Mozart's Requiem is a work perhaps inevitably burdened with our expectations of it: that it should be Mozart's testament, or a consolation for his early death; that it should portentously reveal not only mysteries of humanity and the divine, but mysteries of Mozart, whom history has never quite succeeded in classifying. The musicians united for Thursday's performance gave it both vigor and nuance, as (I thought) more an invitation to contemplate mysteries than an anxiously proposed solution. The soloists, all very fine, worked admirably together in the graceful intertwining, echoing melodies of mourning and prayer. There were one or two moments where Dominique Labelle seemed to have trouble on a breath, but she sang with a wonderfully pure, warm tone. Kelley O'Connor's dark mezzo--focused, but sensual and rich in colors--provided a fascinating contrast. Joseph Kaiser sang with easy, elegant phrasing, and his bright tenor was admirably supple. Even, fluid sonority was contributed by Richard Paul Fink. The members of Musica Sacra--women positioned among the strings and woodwinds, men ranged behind the brass--contributed beautifully expressive choral work. In response to Fischer's cues, they varied the color of their sound to fit the text, an effect especially notable in the "Kyrie." Meditative pauses between movements were employed selectively and effectively by Fischer. In the final movements, reminiscences of earlier phrases and themes emerged clearly. After the final chord, Fischer's baton enforced silence long enough to be reflective rather than merely expectant. And then we stood, and Fischer motioned the orchestra and singers to their feet, and we shared our joy.