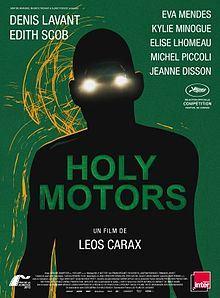

I often wonder whether biographical context is an important factor in understanding a filmmaker’s work. Do I need to know the director’s relationship with their mother to understand a film? Can the film stand alone and entertain? I haven’t been convinced one way or the other (though I lean towards the opinion that a biography is interesting, yet superfluous, to appreciating a film or any work of art) but the two things I knew about Leos Carax were that he hadn’t made a feature film in 13 years, since 1999′s Pola X, and that his new movie Holy Motors had inspired enthusiastic (if bewildered) praise upon its debut in May at this year’s Cannes Film Festival.

Thus, my journey began.

Because I had been anticipating Holy Motors since May and it seemed something excitingly new was upon me I decided to do a little prep work and found that one of his movies was available on Netflix Instant Play, the operatic and inimitable The Two Lovers on the Bridge. I hit play and was instantly taken by this romantic film made in 1991 about Alex and Michele, two drifters falling in love. It’s a film unlike any other I’ve ever seen before, and had much to say about the laws of desire, as well as the pitfalls of falling in love.

Upon viewing the film, I felt prepared for this alleged head-scratcher, but when the time came I found I was not.

Holy Motors follows Monsieur Oscar, played by a revelatory and fearless Denis Levant, on his sojourn through Paris in his chauffeured limousine on a day of work, which consists of nine appointments. Oscar’s first appointment is to dress up as a haggard woman, complete with walking stick and limp, begging for money on a busy walkway only to face the apathy of passersby. Carax keeps the camera static on our subject as she sees many legs pass her, but not one hand gives change to the helpless figure that feebly stands before them. Five minutes later, Oscar is back in the limo and getting out of costume as his chauffeur, Celine, tells him that the file for his next appointment is on the chair.

By the third or fourth occurrence of this pattern, it becomes clear, Oscar isn’t a high-powered businessman in a luxury automobile, as one presumes before he gets into the limo, but rather an actor who has many masks and performances that he must conjure up and provide for an audience invisible to him, though he is aware of their existence. One-third into the film, a man in a suit, waits for Oscar as he comes back into the limousine and informs him that the audience’s interest and belief is waning. This producer/agent/manager/director type encourages Oscar to find his passion and to act believable, for he seems to be slipping and the audience isn’t as taken with his performances. The man’s message is clear: make each scene believable as this is what the audience wants.

The film takes many twists and turns and it’s a struggle to provide a full and accurate synopsis of the movie, thankfully so, as no film critic could possibly ruin the complete movie for you in a single review. Carax made such a beautifully layered film with so many facets, impressively gliding through genres as an aristocrat goes through a 12-course meal. There are touches of comedy, farce, eroticism, and a few others that each vignette itself could be a feature film. Through each vignette, a different story is told, but the spine of the story is maintained and made cohesive by Oscar’s ride in the limo with Celine.

As each vignette lasts only a few minutes and ends just as quickly, the audience is aware that these scenes are intentional. They are not made as a pretense in the direction of whimsy. There is a purpose for each scene as they show how quickly Oscar is forced to change emotion and adopt another character. We know that each emotion is manufactured and conjured within minutes going from musical bandleader to a disappointed father, to an older man on his deathbed as his anguished granddaughter cries at his bedside. At the climax of this particular Oscar gets up in the middle of his granddaughter’s tears and excuses himself, as he doesn’t want to run late to his next appointment. They break character and exchange pleasantries and introductions, and with that Oscar is leaving their bourgeois setting for his next scene. As we see Oscar in the limo after each appointment, the toll and exhaustion his work takes on him grows more apparent. Substituting cigarettes and whiskey for food, fatigue engulfs his emotion-ridden eyes. Strikingly, Carax distorts one of the hallmark symbols of luxury, the limousine, into a mobile office, nay, a mobile dressing room, crammed with wigs, costumes, a vanity mirror, props, and the likes.

I wonder if Carax is in fact commenting on the emotional and spiritual destruction that a dedication to the arts can bring. Having not made a film since 1999, is this a semi-autobiographical story about his thought process? Are these vignettes the writing-equivalent of doodles that he made into one cohesive film? Is Oscar an avatar for the director, and this film a depiction of Leos Carax’s struggle to create? Is the film autobiographical?

Is he, perhaps, saying that this is just modern-life; a series of expected scenes complete with manufactured emotions? The only authentic relationship depicted in the movie is between Oscar and his chauffeur, the patient and understanding Celine; every other relationship is a manufactured one with a pending expiration date. Are human beings just destined to live forever-lonely going from one inauthentic moment to the next?

Halfway through the movie, as these questions swim in my head I’m reminded of a joke I heard a comedian make, that eventually sitcoms will go the way of advertisements, reducing themselves to 30-second segments because that’s all 21st century attention spans can cope with. Are these vignettes just a satirical commentary on 21st century existence? Is it less satire and more the future of filmmaking? Do we have to invest in any character? Can we do away with the foreplay and just have a climax? Is this the cinematic equivalent of instant gratification?

Going into the film I expected a bewildering film, but I did not expect it to say so much. Furthermore, Denis Levant (who also played Alex in the aforementioned The Lovers on the Bridge) is fantastic as Oscar. Carax said that Levant was the only living actor who could play this part and it’s easy to see why. If nothing else this film is a showcase of a fearless actor who is a frequent (infrequent?) collaborator of Carax.

The film is magnificent that even now I still have trouble articulating my feelings about each aspect of the film. There were many questions that arose in my head as I watched the film and continue to knock around in my head well after. Carax, having been out of the game for some time, came back with a film that stimulates the visceral senses as much as it does the cerebral.

Alas, by film’s end I still didn’t have an answer on whether biographical context is important in understanding a film or understanding a filmmaker’s oeuvre, but upon seeing the film I did learn that Leos Carax is an anagram for the filmmaker’s real first and middle names: Alex Oscar.

-Parhom Saeidi