The Bible is an odd book. It is foundational for the modern world, no matter how much we might want to deny it. Even so it’s a strange book. The King James Version (KJV) of the Bible is a masterpiece of English literature. There’s not one King James Version, however, as several variants exist. Nevertheless, the KJV remains quite popular among some religious groups and it is still studied in English Departments as part of our cultural heritage. It is also in the public domain, which means anyone can print and sell it. Unless, of course, you wish to do so in the United Kingdom. Here’s where the story gets interesting.

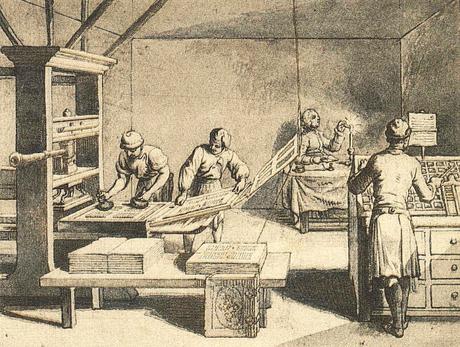

Because of England’s troubled religious history—remember the whole Catholic v. Protestant monarch thing?—the printing of religious books became a contentious issue shortly after the adoption of the printing press. In 1577 a monopoly on Bible printing went to one man, Christopher Barker, the Royal Printer. Ostensively to control the version of the Bible approved for use in the Church (of England), this royal privilege became law. In perpetuity. Now rights, as commodities, can be bought and sold. And this happened from time to time. Cambridge University, however, had been granted a royal charter earlier—also perpetual—to print “all manor of” books. Since this arguably included the Bible (a lucrative business) it wasn’t prevented from printing them as well. Oxford University was granted a similar charter some years later and so the two ancient universities and the Royal Printer were the only ones allowed to print the Bible for sale in the United Kingdom (except Scotland, but that’s a story for a different time).

This privilege, which still exists on the books, did not apply to later versions of the Bible. The KJV became wildly popular and really wasn’t challenged much for over two centuries. By the nineteenth century British lawmakers, presumably, had better things to do than argue about who could print the Bible. Meanwhile other translations divided and conquered the profits coming in from the sale of what had been, in essence “the” English Bible. As late as 1990 the Royal Printer status landed with Cambridge University, so the sale of rights continues. A similar story accompanied the Book of Common Prayer, which has always been in the public domain but can only be printed in the UK by the two major university presses. The story of the Bible is a fascinating one, and since it has shaped western civilization, it seems appropriate to give it the last word: “where your treasure is, there will your heart be also.”