By Alan Bean

By Alan Bean

Six devout and dedicated executives are serving hard time in a Colorado prison and their loved ones don’t understand why. From the perspective of those who worked and worshiped with these men, the fingerprints of racial bias are visible to the naked eye. FBI agents and DOJ prosecutors never saw this as a civil matter, a case of well-intentioned businessmen incurring business debt. Instead, scores of federal officials concluded, in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary, that a Colorado software development company had no prospects of success, no interest in success, and existed for the sole purpose of defrauding business partners. Until you realize that five of the six men at the heart of this story, the public face of the company, are African American, nothing else makes sense.

This instance of wrongful prosecution didn’t just damage individuals, families and businesses, it partially explains why, after more than a decade of effort and the fruitless expenditure of more than a billion tax dollars, the security issues that left America vulnerable on 9-11 remain unresolved. It explains why criminal investigators in Philadelphia and New York City continue to use typewriters and why FBI agents still crank out hard copies of their investigative reports.

IRP (The Investigative Resource Planning Company), an information tech (IT) firm headquartered in Colorado Springs, Colorado had the answers, but the federal government was asking the wrong questions.

Gary Walker’s dream

The IRP dream started in the mind of an IT wizard named Gary Walker. “Gary is a patriot,” IRP employee Cliff Stewart told me earlier this year, “he was a cadet at the Air Force Academy. As close to a technical genius as you can get. He used to tell us, ‘If government agencies had communicated with one another, 9-11 couldn’t have happened.’”

The IRP dream started in the mind of an IT wizard named Gary Walker. “Gary is a patriot,” IRP employee Cliff Stewart told me earlier this year, “he was a cadet at the Air Force Academy. As close to a technical genius as you can get. He used to tell us, ‘If government agencies had communicated with one another, 9-11 couldn’t have happened.’”

Sam Thurman also worked closely with Walker. “I was with these guys in New York at the Millennium Hilton,” Sam remembers. “We had rooms on the 65th floor so we had ringside seats of this big hole where the twin towers once stood. And they were saying, ‘There were buildings twice as tall as this one, and people were leaping to their deaths.’ So I know how passionate Gary was about this stuff.”

“It was centered on the investigation function,” Walker told me when I visited him in prison, “major case investigation. A guy who had been in law enforcement for twenty years had been giving me information about investigation. ‘Everything is still on paper,’ he told me, ‘a computerized system would make our work so much easier.’”

Walker started an IT consulting company called Leading Team and worked on his software in the evenings and on weekends. He was thinking of marketing only to small agencies at first but soon realized that it would benefit larger operations like the FBI and the NYPD as well. Realizing his project was getting too big for a single individual, Walker transformed Leading Team into IRP Solutions. By now, Walker was calling the software CILC (pronounced, “silk”) for Case Investigative Life Cycle.

It wasn’t long before CILC was winning rave revues from law enforcement trade journals. “CILC furnishes you with a starting point for harvesting information,” Bob Davis of policeman.com wrote in February of 2004, “followed by logical steps for investigating and conducting follow-up work. Finally, it steps you through the necessary requirements for submitting your work to the local prosecutor. It can even be set up to remind you to get a warrant, scheduling an autopsy, and sending fibers to the state laboratory for further analysis.”

CILC was designed to move law enforcement agencies into the digital age. “All of the information inputted into the system is properly documented, legible, and uploadable to the server,” Davis wrote. “Also, it can be shared at all levels of your agency without paper shuffling or repetitive typing. This means that units from within your investigation can instantly have access to case information.”

In 2003, a new edition of CILC software was produced to enable all six dozen precincts within the NYPD to communicate with one another. Another iteration of the software, CILC-federal, was designed to allow all the agencies operating under the DHS umbrella to coordinate their investigative efforts while enhancing internal and inter-agency communication.

Clinton Stewart started working with Gary Walker in 1999. “I was responsible for business development,” he told me. “This type of capability was pretty new . . . and these were pretty advanced concepts, so my job was to get them to understand what we had . . . These agencies were in desperate need of our product. The VCF fiasco could have been avoided if they had gone with our product.”

Too big, too complex, too complicated . . .

VCF stands for Virtual Case File. In 2005, Glenn A. Fine, the U.S. Department of Justice’s inspector general, released a report stating that four years after 9-11, the FBI was still generating paper reports and using fifty different data bases that duplicated one another. In September of 2000, Congress handed the IT giant SAIC $380 million to solve these problems. In the wake of the 9-11 fiasco, the FBI requested an additional $70 million and Congress gave them $78 million and added DynaCorp, another IT giant, to the payroll with the insistence that the end date of the project must be accelerated. By the summer of 2004 the expensive software was declared “unfit for use.”

In 2005, the FBI announced that its new Sentinel project would do what VCF had failed to do at an additional cost of $425 million. This time the end-date was 2009 and the Lockheed Martin Corp. received the lucrative contract. By 2011, analysts were calling Sentinel “a case study in federal IT projects gone awry” and complaining about “missed deadlines, budget overruns, and feature shortcomings.” After Lockheed Martin had been paid $325 million without producing significant results, the government issued a stop-work order and started negotiating with smaller, more agile companies.

In a recent interview, FBI Chief Technology Officer Jack Israel explained why industry giants like IBM, SAIC, DynaCorp and Lockheed Martin have repeatedly failed to deliver usable investigative and intelligence software to government agencies.

I’ve been in IT development in government for over 10 years. I started at NSA, then 5 years at the FBI, and I finished about a year at DHS. I grew very frustrated working on large IT programs. Because, by and large, I came to believe that these programs just don’t work. It doesn’t matter who you are, because unless you can logically break them down into very small pieces – I think that’s the way to go – they normally fail. They’re too big; they’re too complex, and too complicated.

Israel offered this diagnosis in the summer of 2012, just after Sentinel finally plugged some of the communication holes IRP could have addressed eight years earlier. IRP’s Clinton Stewart isn’t claiming that CILC could have solved all the FBI’s problems, “but they were at 16% [of where they needed to be] when we talked to them, and our product would have taken them to 85%.”

The little IT firm that could

David Zirpolo

Dave Zirpolo, the only white IRP Solutions executive affected by this case, started helping the company in 2001 but worked as a volunteer until 2003. Dave’s job was to put the CILC software through an unending series of rigorous tests. When I asked him how a little company could succeed where industry giants repeatedly failed he was ready with his answer. “Ease of use set us apart,” he told me. “When I worked with testers I would ask them what was wrong with the software and they’d say, ‘but we don’t even know how it works.’ And I’d say, ‘exactly! I want it to be useable by people who don’t know how to use it. They aren’t going to use the manual; they’re going to jump right in.’”

Cliff Stewart, brother of IRP executive Clinton Stewart, agrees. “The complaint from every law enforcement agency was the same, ‘they are trying to change the way our people work, and they don’t want to change.’ So Gary was taking the software and making it conform to the way law enforcement actually works. That’s why people looked at this product and said, ‘how did you even come up with that?’”

It was this ability to think like law enforcement personnel that led IRP to hire retired FBI agents and NYPD officers to work in house. “We built NYPD protocols into our software,” Zirpolo explains. “We were doing two-month tasks in three weeks and executing exactly the form they wanted. Bu they were like, ‘if you can do that, how about this?’”

Everybody associated with IRP was excited by the intense interest their software was generating in New York and Washington, DC. “We had a bell in the company,” Kendrick Barnes told me. “Any time we had positive word from a potential client we would all get together and ring the bell. There was never any negative feedback.”

All six IRP executives were members of the Colorado Springs Fellowship Church. Chief Operating Officer, David Banks, is the son of Pastor Rose Banks, a charismatic powerhouse who founded the church in 1978 while her husband Charles was a senior non-commissioned officer in Germany. When Charles was transferred to Fort Carson near Colorado Springs, many of the founding members asked to be transferred to the Colorado community so they could continue their association with the church, others moved to the city after retirement. Colorado Springs is a military town and many of the church’s most committed members are associated with the armed forces.

Pastor Rose Banks

Anyone familiar with the Pentecostal worship experience would feel right at home at CSFC. The music, tight, contemporary and rhythmic, is performed with virtuoso verve. Pastor Rose (as she is usually called) prays for the sick and stresses the importance of Holy Ghost Baptism, but the basic thrust of her ministry is love-in-action. “Don’t believe it just because I’m saying it,” Pastor Rose repeatedly implores, “believe it because it’s in the Word.”

Rose Banks doesn’t like “prosperity” preachers who ask for money on television, but she talks about all the practical details of life: money, work, neatness, appearance, efficiency, follow-through, self-respect, marriage, sexual fidelity and all the other subjects preachers normally avoid. Banks encourages her people to get a good education and to look to God for professional direction. She believes in taking personal responsibility but she also stresses the community’s responsibility to care for its most vulnerable members.

“In this church, we mentor each other,” Cliff Stewart explains. “Whatever is your expertise you mentor people in that area.” As church members like Gary Walker and David Banks gained competence in the IT field they naturally became role models for young people. “Demetrius (Harper) and Kendrick (Barnes) got me into the IT field,” one church member told me. “They mentored me and gave me some practical steps to follow.”

Although half of the information technology contractors working at IRP had no relation to Rose Bank’s church, companies that work with intellectual property tend to hire professionals they know and trust and IRP was no exception. The company had no formal relationship to the church, but the business culture reflected the “Make it Happen” philosophy Pastor Rose preaches every Sunday morning and evening.

“Family and friends of IRP came together to assist with the operating expenses of IRP, rent, heat bill, etc.,” Cliff Stewart says. “If that meant taking out personal loans in which someone signed a note, that’s what happened.”

“IRP was run far more efficiently than any other company I have ever worked for,” Sam Thurman says. “Politics was out the window because everybody was on the same team and working toward the same goal. In corporate America there is so much competition and everybody is trying to claw their way up the corporate ladder. It was never that way at IRP.”

So near, and yet . . .

Nothing came easily for the fledgling firm. Federal agencies happily handed the big IT companies millions of dollars with little advanced scrutiny; but official enthusiasm with the capabilities of CILC software didn’t translate into firm contracts and cash flow.

“A former executive with Motorola looked at our product early on and he was really impressed,” Kendrick Barnes says. “But he had a question: ‘What are you going to do when the big boys come?’ At the time, we didn’t know what he was talking about, but it didn’t take long to figure it out.”

“We were playing with a stacked deck and didn’t know it,” Gary Walker admits in retrospect. “A small company without large customers will be asked ‘who else is using it?’ Eventually DHS came right out and said, ‘We would never contract with a company as small as you, but if you will partner with a large contracting company that would be a win-win.”

“Eighty-ninety percent of these companies weren’t interested [in a partnership]” Walker tells me, “the others refused to sign a non-disclosure agreement” that would leave IRP in control of its own intellectual property.

Gary Walker and David Banks

“We had a teaming agreement with Deloitte [another major IT company] and a contract was signed,” IRP COO David Banks says. “They agreed to go after certain opportunities together, and Deloitte could leverage our software. The agreement went through both legal departments. It was an open teaming agreement: our software and their service ability. We were also reaching out to Bearing Point along these lines. We would sell our software through them to the NYPD.”

Temporary frustrations simply made the executives at the helm of IRP Solutions more determined to succeed. In September of 2003, John Shannon, an NYPD detective who had served as Commanding Officer of the Investigative Liaison Unit, was busy arranging a series of meetings with high-ranking NYPD officials. Shannon was convinced that NYPD would be doing a department-wide rollout of IRP’s CILC software in the first quarter of 2004. Upon retiring from NYPD, Shannon joined IRP as a consultant and continued to facilitate business opportunities at NYPD on behalf of IRP.

In late 2004, Bill Witherspoon with DHS told Sam Thurman that he wanted to include IRP in DHS budget exercises for the following year. “One quote was for $120 million for the first phase implementation of the case management software; another quote was $6.2 million for the confidential informant module,” Gary Walker tells me.

The high point came when several IRP representatives attended a private meeting with Robert Gianelli, assistant police chief with the NYPD and a close associate of Police Commissioner Ray Kelly. “He arrived at the hotel, pulls up in a black town car. Gianelli told us, ‘I want this software to be my legacy at NYPD.’”

“We were still working with DHS on modifying the software to accommodate their requests when we were raided,” Walker says. “Then DHS said, ‘that door is closed.’”

On February 9, 2005, twenty-two FBI agents conducted a SWAT-style raid on the IRP headquarters. In the next few months it was revealed that, beginning in March of 2004, FBI Special Agent John Smith had been conducting interviews with the retired FBI officers IRP had hired as subject matter experts. These men had all signed independent contractor agreements stating that they would be paid only upon the sale of the software. Smith then obtained the names of the law enforcement officials with the NYPD and DHS who were in conversation with IRP and started making inquiries.

One of the subject matter experts IRP hired was Gary Hillberry, a retired US Customs official. In an affidavit composed at Agent Smith’s request, Hillberry recalled providing “a detailed sample report of a typical Customs import fraud investigation so that IRP could dissect the sample to understand law enforcement forms and procedures so they could modify the CILC software. We decided that IRP Solutions had a viable law enforcement product and appeared to be moving forward to acquire state and federal law enforcement contracts for their product.”

Smith’s aggressive inquiries explain why, despite expressions of keen enthusiasm from a growing list of potential customers, IRP had been unable to close business in 2004; law enforcement interest in various iterations of the CILC software was tempered by a growing awareness that IRP was the subject of an FBI investigation.

The bogus business theory

Generally, federal prosecutors don’t get involved with a case until the FBI provides them with documented evidence of wrongdoing. The IRP investigation worked in reverse. On March 8, 2004, assistant US Attorney Matt Kirsch received a hand-delivered eleven-page letter from Denver attorney Gregory Goldberg. Two years earlier, Kirsch and Goldberg had worked together in the US Attorney’s Office in Denver, until Goldberg took a job as a corporate attorney with Holland and Hart, the most prestigious law firm in Colorado.

How IRP came to Goldberg’s attention remains a mystery. He may have been approached by an executive of a staffing company that had supplied IRP with temporary workers and was still waiting for its invoices to be paid. He may even have been contacted by one of IRP’s rivals in the IT field. There is presently no way of confirming any of these possibilities.

You can’t understand Goldberg’s concerns until you understand the way staffing issues are handled in the IT world. IT professionals generally work as independent contractors rather than salaried employees. Staffing companies provide IT companies with as many contract workers as they require for as long as they are needed. Contracts normally last as long as a given project and can be terminated at any moment. Staffing companies are paid to handle the legal, payroll and administrative details.

When IRP started making major modifications to its CILC software in 2002 it became necessary to hire dozens of skilled IT professionals and that meant reaching out to staffing companies. Since IRP had no meaningful income at the time, this constituted a challenge.

Gary Walker hired DKH Enterprises, a firm run by his friend Demetrius Harper, to handle IRP’s staffing needs for the enterprise. As a friend of Walker, Harper attempted to raise additional operating capital. The first goal was to attract investment capital, but in Colorado investors were reluctant to back IT start-ups, so Harper tried negotiating a bank loan.

Demetrius Harper

“I was a one-man African American shop when I started DKH Enterprises,” Harper told me when I visited with him in prison. “I had a few lines of credit open, under $10,000, which allowed me to handle short-term start-up expenses. I understood Gary’s vision very well. I went to several banks in Colorado Springs and Pueblo and a third bank, the Integrity Bank in Denver asking for between $250,000 and $500,000 of seed money. I asked the woman at US Bank and she helped me submit my loan and it was denied. Went back for $200,000, it was denied. So it went all the way down to $5,000 and it was still denied. I was told it was related to my credit, even though my credit score was over 740.”

Throughout 2003 and 2004, IRP enlisted the services of information technology contractors to modify the CILC software in response to the stated needs of the DHS and the NYPD.

Excitement was high. In the first quarter of 2003, IRP was on the verge of closing a $375,000 deal with the Colorado Bureau of Investigation. At the time, that would have been more than enough income to wipe out IRP’s debt. Then CBI decided there wasn’t enough money in the budget to purchase CILC.

But there were plenty of bigger fish to fry. Trial testimony reveals that, in 2003, Paul Tran with DHS was talking to IRP about a $12 million pilot project paid out of the budget of the New York Division of Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Tran told IRP that the project would begin in the fourth quarter of 2003.

John Shannon told COO David Banks that he expected the company would close business with the NYPD in the first quarter of 2004. In November of 2004, IRP representatives attended a joint meeting with the DHS and the DOJ that was coordinated by Steven Cooper, the head of the CEE (Consolidated Enforcement Environment) program. When the meeting ended, Cooper said that the FBI was highly impressed with the CILC software. Cooper suggested that, as a small company, IRP should establish a relationship with a large defense contractor or system integrator who could serve as the primary contractor with IRP working as a subcontractor. This was part of the federal government’s Federal Investigative Case Management Solution initiative (later known as Sentinel). This was huge.

In late 2004, in response to a request from Bill Witherspoon with DHS, IRP provided quotes totaling over $100 million. There was no choice but to continue using staffing companies to provide contractors so IRP could fulfill customer expectations, land a lucrative contract, and pay its debts. When Demetrius Harper and David Banks informed staffing companies about their exciting prospects, some balked. IRP had no income and no signed contracts. But other staffing companies agreed to provide contractors for IRP in the expectation that the company’s eventual success would create a steady stream of lucrative business.

“Entrepreneurs believe in their product,” Banks explains. “Entrepreneurs risk more than most people would to get their product out there. If there hadn’t been repeated requests to modify the software there would have been no staffing companies. It’s that simple.”

Harper agrees. “That’s the American Dream, what we’ve been raised to believe: that an entrepreneur can get that contract signed and realize a dream. We felt we had something so new, so dynamic, so cutting edge that if we could get it to the government it would be wonderful. We told staffing companies that if we could sign a contract we would use them for residual business down the road. When we get our first contract we will need to scale up our staff dramatically, and it was that potential that made us attractive. Sometimes staffing companies would approach us because of our reputation. The synergy started to build. They were hoping to get in early and that’s why they were willing to take a chance on us.”

When IRP wasn’t able to close business as quickly as they originally hoped, staffing companies would eventually lose patience. There was no choice but to sit down with a salesman from another staffing company, explain the company’s prospects, and ask them to take a chance on IRP.

“Every day we came into the office, we truly believed that a contract was imminent,” Gary Walker explains. “From 2002 right up to the raid, we felt we were going to close business for at least a million dollars in the near future. The staffing companies saw dollar signs waiting at the end of their business relationship with us. In the end, because of the way the government stopped our business, they didn’t get paid.”

“The only reason we were engaging these companies is because we were being asked to continually alter the software,” David Banks explains. “Every time we made a change we expected them to make a decision and they wouldn’t. We had to decide whether to stop (in which case we would never be able to pay our creditors) or keep trying to secure a contract.”

Throwing in the towel was never an option. “When you’re talking to large law enforcement agencies and they are giving you positive feedback it makes you feel that any day you will sign a contract,” Walker says. “It never crossed my mind that I should pull the plug.”

Demetrius Harper was so confident that IRP would succeed that he signed a personal guarantee with more than one staffing company. “When you sign your name and say I will pay you back, that if my business falls apart you can come after me, that really shows how seriously I took my financial obligations,” he told me when we talked in prison. “And I still believe we will be able to do that because my word is still out there.”

The first grand jury that heard FBI Special Agent John Smith testify about IRP’s debt situation refused to indict. “But if I don’t pay somebody for work they’ve done, that’s not a federal crime,” one grand juror pointed out. No one questioned the staffing company’s obligation to seek civil remedies, but so long as IRP executives were making a good faith effort to secure a contract, where was the fraud?

Grand jurors realized that no one had forced the staffing companies to do business with IRP. In most cases, a Dun and Bradstreet credit report would have flagged the company as a credit risk. If a staffing company knows IRP won’t be able to pay invoices until they land a contract, and they do the deal anyway, they had to deal with the consequences. The grand jury understood the point staffing company executive Andrew Albarelle explained in a letter years later:

Staffing firms are called upon to staff contractors on projects. We are asked or we solicit companies and then find people to match job requirements. We pay our contractors a ‘pay rate’ and charge our clients a ‘bill rate’. The difference between the two is called the ‘spread’ or ‘margin’. This is how staffing firm make money. We are called upon daily to decide with whom to do business. There is no gun put to our heads and we are free to choose who we engage with.

Denver attorney Gregory Goldberg

The government’s case against IRP has always rested on a foundation of suspicion laid by former federal prosecutor Gregory Goldberg. Having learned that a handful of staffing companies wanted IRP to pay up, Goldberg jumped to unwarranted conclusions. In his eyes, IRP was a bogus business only pretending to develop software so they could defraud staffing companies.

Although IRP representatives “always acted as though they were running a legitimate business,” Goldberg stated in his letter, men like Banks and Harper actually “operated bogus business entities with the specific intent of executing a scheme for obtaining money from (staffing) companies . . . under the guise of working in conjunction with law enforcement.” The government’s case never departed from this bizarre misreading of the evidence.

In his search warrant filed in February of 2005, Special Agent Smith referenced IRP’s “purported software”. Smith was transferred off the IRP case after failing to gain an indictment and was replaced by a more experienced agent, Robert Moen. But even after being assured by dozens of witnesses that CILC was a viable product that lived up to IRP’s glowing advertisements, Moen stuck with Smith’s term, “purported software”.

Remarkably, neither Smith nor Moen knew no more about IRP’s software than had attorney Goldberg. Asked by a grand juror in June, 2009 if CILC was a viable product, Moen said he couldn’t answer the question because he had never witnessed a demonstration of the software. Smith had, however, talked to people like the FBI’s Melissa McRae who had attended presentations featuring IRP’s CILC software. Two FBI agents spent five years investigating IRP without once examining the product they were marketing to law enforcement, and then made dismissive references to “purported” software. The ignorance was intentional.

The persistence of a bizarre theory

What made Goldberg so sure that CILC wasn’t a viable product? There are two possible explanations, one related to legal, the other steeped in America’s tragic racial history.

The IRP defendants couldn’t be charged with a felony if they were making a good faith attempt to market a viable product to interested clients. This is an “intent” case. The six IRP defendants who stood trial in 2011 either intended to make good on their debts by selling their software, or they intended to rip off staffing companies using faux software as bait; the motivations are mutually exclusive. If IRP executives were trying to market their software, they were serious about repaying the $5 million dollars they owed to 42 staffing companies. If the goal was to defraud these companies, all their talk about pursuing business with big law enforcement agencies was a carefully crafted joke.

Goldberg had recently left the US Attorney’s Office in Denver and hadn’t abandoned the prosecutorial mindset. Attorney Harvey Silverglate argues that federal law has become so opaque and labyrinthine that even the most scrupulous business executive commits three federal crimes a day. If the feds want to put a person in the business world behind bars, Silverglate says, they can find a way to make it happen.

Greg Goldberg wasn’t satisfied with civil remedies; he wanted to put people in prison, and that meant IRP executives had to be running a “bogus business”.

But why was Goldberg so eager to portray hardworking family men like Gary Walker and David Banks as street hustlers?

In November of 2012 I spent an entire day interviewing several dozen members of Colorado Springs Fellowship Church who have been personally impacted by what they call the “IRP-6” case. When I asked one group why the federal government was portraying IRP as a bogus business and a criminal enterprise the response was immediate. These comments are typical:

Joe Thurman : “Here in Colorado, especially in Colorado Springs, five black guys starting a company and they are on the radar for sure.”

Tara Goggans: “It’s like they stepped into a circle where they didn’t belong. If you want to start a trucking company or a lawn care company, that’s all right, that’s what you’re supposed to be doing. But this is intellectual property, that’s intellectual work, what are you guys doing?”

Cliff Stewart: “Five black guys together and its guaranteed, crime’s coming. In corporate America, let more than two black guys get together at any company and you better disperse quickly because people will assume you are planning some kind of criminal activity. As a black man in corporate America it is so blatant. If we have three guys together we have to disperse because security will be showing up. Even if you are going to lunch together, you had better meet on the street, not in the building.”

Craig Lowry: “In the eyes of the federal government, these guys aren’t about helping law enforcement, they’re about running drugs; they’ve probably got a bunch of hoes back in there. Oh no, these coons are up to something and we need to tear them down.”

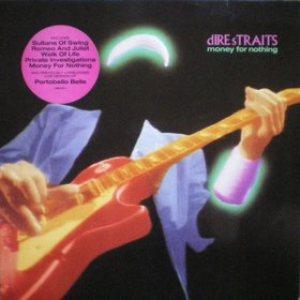

During the 2011 trial, AUSA Matt Kirsch presented the IRP defendants as slick opportunists who had learned to game the American dream. “These aren’t real entrepreneurs developing a viable product in response to consumer demand,” Kirsch implied. “Black guys can make money running, jumping, slinging dope and rapping; but they don’t develop software.” Craig Lowry’s “they’ve probably got a bunch of hoes back in there” nicely captures Kirsch’s coded message to the jury. It was like the old 80s Dire Straits song about the “yo-yos” who get paid to “bang on bongos like a chimpanzee” while the honest working man sweats to earn an honest dollar:

During the 2011 trial, AUSA Matt Kirsch presented the IRP defendants as slick opportunists who had learned to game the American dream. “These aren’t real entrepreneurs developing a viable product in response to consumer demand,” Kirsch implied. “Black guys can make money running, jumping, slinging dope and rapping; but they don’t develop software.” Craig Lowry’s “they’ve probably got a bunch of hoes back in there” nicely captures Kirsch’s coded message to the jury. It was like the old 80s Dire Straits song about the “yo-yos” who get paid to “bang on bongos like a chimpanzee” while the honest working man sweats to earn an honest dollar:

That ain’t workin’

That’s the way you do it,

Money for nothing and your chicks for free.

Kirsch told the jury that the IRP executives on trial, and every man and woman who worked for their company, was interested in one thing: money for nothing. That was the government’s case.

Is this what Gregory Goldberg was thinking when he concocted the bogus business theory? We can’t know. But it may have been what he was feeling deep down where the filters of political correctness disappear.

Everyone, whether in the US Attorney’s Office, the FBI, or the business world who brushed up against Goldberg’s “bogus business” hypothesis was instantly persuaded. Susan K. Holland was president of ETI, a Denver-based staffing company, when she agreed to provide staffing services for IRP in late 2003 and early 2004, a period when the company’s expectations of success were sky high. Holland was deeply impressed by Demetrius Harper when he told her about the product IRP marketing to law enforcement agencies. In February of 2004, after IRP hadn’t paid several months of ETI invoices, Holland sent Harper a glowing email in which she hailed him as Colorado’s next “self-made millionaire”.

Then everything changed. On April 29, 2004, Holland sent Harper a string of increasingly insulting emails in which she ridiculed him as a “con artist” who was running the kind of scam Goldberg outlined in his letter to the US Attorney. We don’t know if Holland took her new opinion directly from Goldberg or whether she got the message second-hand through Special Agent Smith, but the well-connected businesswoman was instantly transformed.

Harper responded that the agencies IRP was talking to were “still reviewing the solution and have not been expeditious in moving forward.” He told Holland he would be deeply relieved when ETI was paid in full and wished her a blessed day.

Susan Holland is not a racist in the conventional sense, but the moment someone suggested that Harper might be a street hustler running a “bogus business” she believed it and responded accordingly. “Your name will be destroyed,” she told Harper. “Oh, and by the way, I want your Cadillac and your Audi.”

Every dime of the money IRP received from staffing companies went to pay for contract labor, and only 12% went to IRP executives who were also staffed to work on the projects as billable consultants; an accepted practice in the IT consulting field. Between 2002 and 2004, IRP executives were making between $20,000 and $80,000 per year, a sharp reduction from the years when they worked as independent contractors in the IT field. Dave Zirpolo worked as a volunteer for well over a year before joining the staff at a salary of $60,000. Demetrius Harper had purchased the vehicles Ms. Holland referenced in her email long before partnering with IRP.

Unanswered questions

Why did the U.S. Attorney’s office waste taxpayers’ dollars criminalizing a debt collection case? The only justification is the bogus business theory: IRP wasn’t a real company marketing a real product; it was a scheme to create fake jobs and free money for unqualified louts who couldn’t get real jobs with real companies.

But proponents of the bogus business theory have never explained why a group of successful IT professionals would give up thriving careers to run a scam that offered lower pay and longer hours?

And if the IRP defendants made such odd career moves, what kind of end game did they have in mind? Everyone knows what happens to bogus businesses marketing fake products; they end up in bankruptcy court facing a long string of civil suits. Careers and credit ratings are destroyed.

Moreover, all the friends who initially benefited from fake jobs and free money will be linked to the scam. Everyone associated with the bogus business could be indicted for fraud.

This isn’t something that might happen; it is inevitable. The end game of a bogus business is entirely predictable. That’s why genuine scammers have an exit strategy, a way of disappearing into the night when the game is up.

The IRP-6 had no exit strategy, no escape hatch. In fact, if they were released from prison tomorrow, they would reconstitute their company and return to work.

Finally, when scams unravel, everyone associated with the scheme is desperate to distance themselves from the bogus operation or, desperate for lenient treatment, they rat out their former employers and associates. The behavior of the experienced and highly-trained men and women who worked for IRP doesn’t fit this model. No one is pointing fingers; everyone continues to believe in the company, the product it created and the men who hired them.

The IRP case departs from the typical failed-scam scenario for the simplest of reasons: the government’s case can’t stand up to scrutiny. The fraud alleged in the federal indictments is a mirage. The bogus business theory is bogus.

The Raid

Just over twenty people were working in the IRP headquarters in Colorado Springs when two dozen armed FBI agents forced their way into the building. Although they knew they were raiding a predominantly black business, every agent involved in the raid was white. Dave Zirpolo, the only white IRP employee in the building at the time, is still trying to come to wrap his head around the experience.

“There is video surveillance of the raid,” he told me when we talked in prison. “An FBI agent politely asked me to go to the lunch room and I sat there for twenty minutes while they took names and contact info. They told me I could go, so I went to my office. An agent asked me if I was leaving and I said I was. He handed me his card and said ‘Hey, if you want to talk, give me a call.’ No one else got this message. I left the building assuming this was how it would be for everyone else. The moment I left it was like mayhem. There’s footage of me leaving and there’s footage of black employees being dragged back in when they attempted to follow me out the door.”

“This has opened my eyes tremendously,” Zirpolo says. “I was raised to believe that the government was there to help you, and I no longer believe that. I knew there was racism in the world, but now I realize it is far worse than I had imagined. If we had all gone to a Catholic Church they never would have done this. If this was a white company, they would never have done this.”

IRP Solutions Headquarters in Colorado Springs

The eighty people I interviewed at the Colorado Springs Fellowship Church are still struggling with the emotional aftermath of the raid. “We enjoyed our work,” Lisa Stewart told me in a hushed voice. “There was so much good stuff going on, all the prospects and possibilities and knowing that they were on the verge of closing business any day. But after (the raid) there wasn’t the same feeling. It was like being raped. It just shook everything, and nothing was ever the same.”

“And the humiliation that went with that,” Janette Williams added. “It was like walking into a place that was once clean and now it was dirty. And you’re going up the elevator with people in surrounding businesses and they are looking at you as if there must be something wrong with you because they saw what had happened. And it was just like having a sick, sick feeling in your stomach.”

Special Agent Smith worked the stigma associated with a SWAT-style FBI raid to good advantage. Counter to official policy, he leaked information about the raid to the local press and then forwarded the article in the Colorado Springs Gazette to the staffing companies who had done business with IRP. Significantly, Smith also faxed the story to Gregory Goldberg, the Holland and Hart attorney whose “bogus business” theory initiated and shaped the FBI investigation.

“It was like they were trying to do a drug raid or something,” Gary Walker’s wife, Yolanda, told me. “I was at my mother’s house when I got the call. We went to IRP’s offices but when we arrived the FBI wouldn’t let us in. They arrived at nine in the morning and didn’t leave until 10 that night.” During this period, many of IRP’s black employees were held in the cafeteria.

Norman Bowden, Kendrick Barnes’ stepfather, is career military. “Now I know how the black soldiers felt after World War II,” he says. “They fought for their country, but when they got home there was no freedom. I’ve known Kendrick, David and Demetrius since they were little kids. They were raised to serve God first and obey the law of the land. They were trying to do the right thing, creating software for law enforcement, and then law enforcement comes in and raids them.”

Several employees felt they were being treated like street thugs. “They came in with so much noise, Barbara McKenzie recalls. “If you’re a law-abiding citizen, you’re not prepared for this kind of behavior . . . It was their attitude that irritated everybody because it was so unnecessary. We’re just ordinary people trying to do our jobs.”

Lisa Stewart was attempting to call her mother on an office phone when one of the FBI agents slammed down the receiver. “You don’t make any phone calls; don’t even touch that phone,” the agent said. When Stewart protested, a second agent slapped a set of handcuffs on the desk and yelled, “Do you want to go to jail?”

“I said, ‘Sure, take me to jail. You think black people are afraid of jail?’ My brother, David Banks came over and told me to go to the cafeteria like they wanted me to do. I wouldn’t have gone if David hadn’t said that.”

Cliff Stewart was also having a hard time containing his emotions the day of the raid. “They had us all in the cafeteria and at one point I just left. I told them, ‘I don’t care what you guys say; I don’t appreciate what’s going down here.’ John Smith grabbed my arm, and I told him to get his hands off of me. But Gary Walker came up and told me to settle down and cooperate with the agents; so I went back to the cafeteria.”

The warrant cited the seizure of financial records as the purpose of the raid, but real intention seemed to be imaging all the IRP computers that contained anything related to IRP’s CILC software.

The broad brush of suspicion

It was soon obvious that the FBI saw Colorado Springs Fellowship Church as little more than a front for money-laundering. The FBI made several warrantless searches of church member’s bank records and several people learned that their neighbors had been interviewed.

“They started asking me about my affiliation with the church at my job,” Shaun Haughton says, “and my employers were told by the FBI that they suspected the church of money laundering. When the FBI interviewed me they said they had a file of IRP employee folders. ‘There’s a good pile, and there’s a bad pile, and if you will tell us what’s going on here we’ll put you in the good pile.’ It was highly offensive.”

When the grand jury was convened in 2007, several church members were subpoenaed and peppered with questions. Gwendolyn Solomon, an attorney with an IT background and a member of Colorado Springs Fellowship Church, learned that two neighbors had received a visit from an FBI investigator who asked questions about her.

Eventually the FBI realized that there were no financial links between the church and IRP and that every penny of the money obtained from staffing companies could be legally accounted for. Though unable to obtain an indictment from the grand jury, the US Attorney’s Office refused to walk away empty handed. Lawanna Clark, the Pastor’s daughter and a volunteer at both the church and IRP, was convicted of perjury. Lawanna told the grand jury that she had not signed a bank withdrawal slip and the prosecutor insisted she had. After trial, an independent handwriting expert confirmed that, although the slip bore Lawanna’s name, the signature had been made by her sister Yolanda. Yolanda had her sister’s permission to sign her name as a proxy. Judge Christine Arguello was aware of the expert’s testimony yet refused to grant a new trial. The appeals court followed suit.

“When they took ‘Wanna and she spent six months in prison, we flew back and forth to Arizona every weekend. We made sure that someone was there to see her,” Brenda Linton remembers. “Each time when it was time to leave and you would look at Lawanna, and you knew we were leaving our sister behind in this prison. The pain was awful.”

Barbara Johnson agrees. “What they did to Lawanna was a kind of rape. The perpetrator disappeared into the shadows and there were no consequences.”

Redemption denied

The raid on IRP headquarters had a crippling effect on the six executives at the heart of the government’s investigation. “It took me a year and a half of counseling to get them to stand on their feet and fight for their lives,” Rose Banks told me. “I had meetings and meetings just with them. And I told them, ‘Don’t die with the prize in your hand.’”

For a time Gary Walker considered abandoning the software business. “He was a genius in software development,” Cliff Stewart remembers. “To see him in his garage doing wood working it was disconcerting.”

But eventually the six men returned to jobs in the IT industry and continued work on their CILC project in the evening and on weekends. “After the raid we did things on our own time,” Kendrick Barnes recalls. “We were contributing to plane tickets for IRP business travel, we were working other jobs and after hours we were still working on CILC.”

But wherever they tried to market their software the government got there first. Barnes believes the FBI was monitoring their every move. “Every time we tried to do a deal, somebody from the FBI would head us off and say, ‘These guys are under investigation and an indictment is coming down’.”

Finally, in late 2008, everything seemed to be coming together. In a letter to Everett Gillison, Deputy Mayor of Public Safety with the City of Philadelphia, David Banks made an audacious offer. “IRP has developed the most comprehensive enforcement and investigative solution available in the world today. We are so confident that our software solution will improve law enforcement operations and efficiency that we are willing to deliver and implement this key module at absolutely NO CHARGE and let you and Police Commissioner Ramsey experience the benefits firsthand.”

“We hoped that when they saw that the software worked they would invest in more advanced modules,” Kendrick Barnes says. All the city would have to pay for was a customization, configuration and maintenance fee.

Establishing the viability of their product would immediately catch the attention of other jurisdictions and lead to additional orders, cash flow and the ability to finally discharge the company’s debt.

Philadelphia jumped at the opportunity. As the IRP executives knew, IBM had been handed a $4.7 million contract in 2002 to computerize the department’s records, but seven years and $7.1 million later IBM had failed to deliver and Philadelphia officials were still fuming.

On January 19, 2009, Lorelie Larson with the Office of the Inspector General informed Banks via email that “All of the OIG staff is very excited about this venture.”

A month later, Gery Cardenas, Director of Information Technology for the Philadelphia Police Department was telling FBI agent Jennifer Ngo that “PPD was very close to having the (CILC) product installed prior to the discovery of the IRP investigation.” According to Ngo’s interview notes, the CILC module “seemed to look exactly like what Cardenas and the PPD was looking to purchase.”

A simple phone call from Matt Kirsch in the Denver US Attorney’s Office instantly scuttled the deal. “Kirsch couldn’t allow the software to get any kind of viability,” Barnes laments. Kirsch told Philadelphia officials that IRP would soon be indicted for a second time. In truth, it would be six months before the government presented the IRP case to a second grand jury, but a signed deal between IRP and Philadelphia would have derailed the government’s case. If IRP succeeded where IT giants like IBM and Motorola had ignominiously failed the nationwide response would have been phenomenal. More significantly, it would have validated IRP’s contention that the DHS and the NYPD were poised to invest in CILC software as early as 2004.

The government’s new theory

When the case went to trial in the fall of 2011, the jury never learned that the federal government had repeatedly frustrated IRP’s attempts to conduct legal business. Just as significantly, the numerous staffing company representatives who testified didn’t know that the FBI and the DOJ had undermined IRP’s ability to discharge its debt.

When Matt Kirsch faced his second grand jury, he was determined to get an indictment. John Smith had been a raw rookie when he testified before the first grand jury in 2007, and it showed. His answers were imprecise, rambling and strewn with errors. Unlike Lawanna Clark, Smith didn’t have to worry that a verbal slip might put him in prison, but his shoddy work on the IRP case did get him transferred to Arizona.

Smith’s replacement was Robert Moen, a twelve-year FBI veteran. The government’s strategy had shifted considerably. There were no more dark hints about improper financial arrangements between IRP executives and their church, and AUSA Kirsch now claimed that the viability of the software was a non-issue.

The issues Kirsch raised in 2009 had hardly been raised two years earlier. Kirsch accused IRP representatives of falsely representing to staffing companies that they had signed contracts with government agencies that would soon provide them with a secure income.

To shore up the first line of attack, Moen re-interviewed dozens of staffing company representatives, asking them if IRP representatives had ever claimed to have signed contracts with agencies such as the DHS and the NYPD. The question hadn’t been asked during the first round of interviews in 2004 and 2005 and no one had volunteered that they contracted with IRP because they falsely claimed to be milking the government’s cash cow.

But during the second round of interviews several staffing company salespeople reported that they would never have done business with a fledgling IT start-up unless they were already doing business with the government. This allowed the potential witnesses to keep the FBI happy while diverting attention from the embarrassing fact that forty-two staffing companies had signed contracts with IRP because they were impressed by their product and business prospects.

The new “contract theory” also provided a partial explanation for why most of the staffing companies failed to run a credit check on IRP and why those who did blithely disregarded the results.

Moreover, Moen noticed that several of the IT developers who contracted with IRP had billed the same hours to more than one staffing company. Kirsch liked the “double-billing” angle because it portrayed IRP as a cash cow designed to make the friends and family of the defendants wealthy by ripping off staffing companies. The implication was that people were paid to do nothing. How, the government asked, could one IT professional bill two staffing companies for the same hours?

None of the staffing companies had ever suggested that they were being billed for hours that were never worked. But several witnesses claimed they would have been distressed had they known that some workers were billing two staffing companies for the same hours.

Two months before trial, Andrew Albarelle, Principal Executive Officer with The Remy Corporation, a Denver-based staffing company, wrote a letter to US Attorney John Walsh explaining how staffing companies actually work. “In our due diligence of companies,” he explained, “we have found that the term ‘contract’ has little-to-no bearing on whether we engage with that company or not. We base our decision to engage with a company on its credit-worthiness, cash flow or the product they are developing.”

The implication of Albarelle’s argument were obvious. Since IRP possessed no meaningful cash flow and couldn’t pass a credit-worthiness test, the business decisions of the staffing companies must have been driven by the future promise of IRP’s CILC software.

Albarelle’s letter to Walsh also addressed the double-billing issue. “It is common practice for contractors to simultaneously work multiple contracts and charge the contracting company full-time hours weekly,” the staffing company executive wrote. “This often occurs with full knowledge or even encouragement by the staffing company.”

So long as the work is done to the satisfaction of the contracting company, Albarelle was suggesting, a single IT contractor monitoring two computers would produce more overall income for the staffing industry. In a proffer submitted to the Attorney General’s Office prior to trial, the defendants presented actual time sheets, invoices and paystubs from Michelle Harris and William Williams, contractors who had worked three different projects for three separate companies and billed eight hour days for each. None of this work involved IRP. The prosecution had solid evidence that multiple billing was a common practice in the IT world but chose to ignore it.

Walsh quietly passed Albarelle’s letter to AUSA Kirsch. When the defendants put the staffing executive on the stand, Judge Christine Arguello refused to qualify him as a subject matter expert. As a consequence, the jury was never exposed to the critical information Albarelle shared in his letter to Walsh.

Going it alone

Federal Judge Christine Arguello

Federal Judge Christine Arguello was appalled when she learned the defendants had released court appointed counsel and made little attempt to conceal her contempt during trial. The defendants navigated the courtroom with considerable skill, but Arguello’s adversarial stance created constant challenges.

Each defendant had been assigned a separate attorney which meant there was no division of labor on the defense side. Potential witnesses weren’t being interviewed in a timely manner and no one was talking to potential witnesses from the staffing companies. The defendants believed their defense required a thorough understanding of the IT world, a subject that was of little interest to their public defenders. Moreover, court appointed counsel, distracted by other cases, was largely ignoring the mountain of discovery material the government had produced nor were they requesting paralegal assistance or expert witnesses.

The defendants concluded that their public defenders assigned were holding out for a plea deal and hoping that one of the defendants would “flip” on his friends. These suspicions are understandable. In the federal system, public defenders lose 98% of the cases they defend, so a measure of fatalism is part of the culture. As William Stuntz argued in his magisterial The Collapse of American Criminal Justice, the primary problem with the court system is excessive prosecutorial power. “Over the course of the past few decades,” he wrote, “prosecutors have replaced judges as the system’s key sentencing decisionmakers, exercising their power chiefly through plea bargaining.”

When defendants know they have a one-in-fifty chance of prevailing at trial and that they will receive ten years if convicted but only six months if they take a plea, the issue becomes a no-brainer. This explains why only 2% of federal cases, no matter how weak, advance to trial. When defendants insist on their day in court, hopelessly overworked prosecutors, public defenders and judges must invest large quantities of time and money they don’t have. Stuntz calls guilty pleas a “budgetary necessity”. Faced with these realities, public defenders often conclude that the best way to help their clients is to keep them out of the courtroom.

An entirely different logic applies to defendants with deep pockets. If IRP had been IBM, they could have enlisted the services of a skilled corporate attorney like Greg Goldberg. If the money was right, an attorney like Goldberg could dispense a team of attorneys and paralegals to sift through discovery materials, anticipate the government’s trial strategy, interview all the major players in the case, and bury the court in a blizzard of procedural motions. Faced with a well-funded opponent, Matt Kirsch would have folded his tents and disappeared into the night.

Having decided to take their fate into their own hands, the IRP defendants began working around the clock, often through the night, wading through oceans of discovery material, exploring trial strategies, anticipating a wide range of scenarios, conducting mock opening and closing statements and picking up pointers from experienced atto

Judge Arguello made some allowances for the defendants’ inexperience, but her pro-prosecution bias was on display throughout the trial. The defendants tried to get Arguello recused from the case, noting that she had once worked for Holland and Hart, the firm Greg Goldberg joined in 2002. Arguello and Goldberg had been candidates for the same federal judgeship in 2008, and Goldberg, graciously acknowledging defeat, told the Denver Post that he knew Arguello very well and felt she would do a good job.

The bogus business theory returns

The trial followed a mind-numbingly predictable pattern. Staffing company witnesses would tell Kirsch they had been assured that IRP had signed contracts with law enforcement agencies. The defendants would produce email correspondence in which IRP representatives celebrated the promise of their software while making it perfectly clear that no contracts had been signed with the government.

Toward the close of the trial, the defendants subpoenaed FBI agent Robert Moen so they could quiz him about discrepancies between earlier and later FBI interviews with staffing company reps. Moen suddenly disappeared on a hunting expedition to the most remote part of Colorado. When a friend of the defendants attempted to serve the subpoena at Moen’s home, an FBI agent told him to stop trying to serve the subpoena because Moen wouldn’t be testifying.

The government argued that Moen’s testimony wasn’t important and the Judge agreed.

Because the government, without prior warning, rested its case a week-and-a-half earlier than anticipated, the defendants’ witness schedule was thrown into disarray. After two failed attempts to produce witnesses led to delays, Judge Arguello made little attempt to disguise her irritation. Nor did she use her judicial authority to compel defense witnesses (primarily government employees) to testify. If the defendants couldn’t produce a witness, she announced during a sidebar discussion, either one of the defendants would have to take the stand or she would force them to rest their case prematurely. In the end, Kendrick Barnes took the stand and responded to questions from AUSA Kirsch by evoking his Fifth Amendment rights. Attorneys for the defendants attempted to raise the issue on appeal but were amazed to discover that the relevant portions of the trial transcript had mysteriously disappeared—an issue that has yet to be resolved.

Although Judge Arguello ruled early on that the viability of the CILC software was not at issue, Matt Kirsch was determined to make it the issue. The officials with the DHS and NYPD who testified at trial consistently minimized their interest in IRP’s CILC software, but since most of them had witnessed repeated IRP demonstrations they couldn’t deny that they had been very interested in the product.

Paul Tran testified that his primary goal was to find software that would allow the 22 agencies under the DHS umbrella to enhance their investigative capabilities and the effectiveness of their internal communication. Tran told Kirsch he had been asked to look at CILC because the New York office was excited about its potential. “A main group from IRP come up to show us the software,” Tran testified. “If I remember correctly, it is called Case Investigative Life Cycle, CILC. And the software had a lot of features that the law enforcement and case agent can really use, can utilize.”

On the basis of this initial demonstration, DHS asked IRP to give them a module of CILC to test. In May of 2004, DHS officials asked for a second CILC demonstration that involved “new features that IRP said that they have added to the software.” Shortly after this meeting, IRP’s Sam Thurman was informed that DHS would be conducting a thirty-day test of the software after which CILC would be added to the list of approved software DHS agencies could purchase.

Cross-examined by Gary Walker, Tran testified that the delay in placing CILC on the approved list simply meant that further testing was needed. The problem, Tran said, had nothing to do with any fault with CILC software; the challenge was to incorporate CILC into the operating system DHS was using at the time, and that required additional modifications. An email from Tran reveals that IRP was eventually added to the list of software companies DHS was approved to deal with.

Email evidence revealed that DHS was particularly interested in CILC’s confidential informant model and that conversations continued until December of 2004, less than two months before the raid on IRP headquarters. When William Witherspoon, another DHS official, was asked if he was aware that IRP was being investigated by the FBI at that time, he said he was not.

Perhaps not. But the poison from Greg Goldberg’s bogus business theory had been spreading for nine months when Witherspoon asked IRP for price quotes in late 2004. FBI interview notes make it clear that several key players within the DHS and NYPD had been interviewed in connection with the IRP investigation in the latter part of that year.

Even if DHS officials didn’t realize the FBI was investigating IRP, the raid in early 2005 put an effective end to IRP’s negotiations with law enforcement agencies. Suddenly federal officials were being asked to explain why they were talking numbers with a gang of scam artists. The defendants were disturbed to learn that the government had conducted extensive conferences with many of the government employees the defense had called as witnesses. Had these individuals been coached? Did prosecutors issue subtle threats or inducements? There was no way of knowing, but again and again, officials who once had been excited about IRP’s CILC software affected indifference on the witness stand.

In the federal system, the government is allowed two closing arguments with the defense close sandwiched in between. Matt Kirsch waited until the defendants had no chance at rebuttal to show his true colors. IRP wasn’t interested in selling software to law enforcement, he told the jury; the company existed to “maximize the money that they were getting from the staffing companies for themselves, for their friends, for their family.” The software was just a distraction. Kirsch informed the jury that IRP had about as much chance of landing a contract with the DHS or the NYPD “as they had of winning the lottery. They knew they weren’t going to get those contracts.” In the eyes of the government, IRP was a make-work project designed for posers too incompetent to make honest money. In this view, IRP executives knew they didn’t have a chance of selling their software because it wasn’t a serious product. Greg Goldberg’s bogus business theory flies in the face of all the available evidence but it started an FBI investigation in 2004 and shaped the government’s closing appeal to the jury seven years later.

The viability of IRP’s software, an issue that should have been effectively settled when the city of Philadelphia embraced CILC in 2009, was at the heart of the government’s case against the IRP-6. The only thing standing between forty-two staffing companies and a paid-in-full check from IRP was the government of the United States. On two occasions, in 2005 and in 2009, FBI and DOJ interference kept IRP from paying its debts while making an extraordinary contribution to national security.

Why then did twelve jurors conclude that the IRP-6 were guilty as charged? The conviction stems, in large part, from what the jurors learned and what they were kept from learning.

- Jurors learned that IRP owed a lot of money to a lot of angry people.

- Jurors learned that many of the people who worked for IRP were friends and family members who attended the same church.

- Jurors heard public officials minimize their interest in IRP’s CILC software.

- Jurors noted that the defendants entered the courtroom without defense counsel and heard Judge Christine Arguello badger, belittle and insult the defendants throughout the trial for having the temerity to represent themselves.

- Jurors never learned that, apart from government interference, the faith staffing companies placed in IRP would have been handsomely rewarded.

- Jurors never learned that IT contractors routinely work for more than one staffing company in a single eight-hour day and bill accordingly.

- Jurors never learned that IRP had successfully negotiated a contract with Philadelphia officials.

Jurors have been remarkably reluctant to discuss the case. A week after trial, a juror was contacted by a person who wanted to discuss the case. Since jurors in this case, contrary to American law, had been told not to discuss the case with anyone, the juror called Matt Kirsch and informed him of the situation. The next day, the juror received a call from the FBI asking for additional information and was told that if anyone else asked about the case the FBI officer should be called so they could “take care of it.”

A tragic aftermath

Following trial, the IRP defendants were held in custody for 42 days before being released pending the sentencing hearing. Their loved ones were shocked by the harshness of the sentences Judge Arguello handed down. David Banks and Gary Walker were sentenced to serve 135 months in federal prison, just over eleven years without parole. Clinton Stewart, Demetrius Harper and David Zirpolo were sentenced to 121 months, almost exactly ten years. Kendrick Barnes received a sentence of 87 months, just over seven years.

Talk to the people who know the defendants best and the anguish is palpable. “Gary had a dream after 9-11 that something like that would never happen again,” his wife, Yolanda says. “All the agencies would pull together and he wanted to be a part of that. He sacrificed family time. My son suffers from seizures, and he is getting worse because of the stress. I almost get sick to my stomach when they talk about the greatness of America. It isn’t true.”

Sarah Harper, the mother of Demetrius Harper, can hardly contain her grief and bewilderment. “Demetrius usually held down two jobs, never into drugs, never a problem. From the time he was five until now, he was raised in the church. He was taught to respect the law of the land and to fear God. He has a seven year-old son, who keeps asking ‘Dad, when are you coming home?’”

“It is very difficult to see the effect that it has on him,” Tasha Harper, Demetrius’s wife says. “His friends ask my son what happened to his father and he tells them, ‘My daddy’s out of town.’ What’s he going to say, ‘My daddy’s in jail’? These are all good men who took care of their families . . . we have a government that prosecutes small business and bails out big business.”

Ethel Lopez is a key organizer with A Just Cause, the criminal justice reform organization that emerged from the ashes of this case. She can’t understand why the media and advocacy groups have been slow to take an interest in the IRP-6 and those who support them. “When I tried to reach the Washington Post the first time,” she says, “the reporter asked me, ‘why would something that happened in Colorado affect people here?’ I told him this is not just about these six men. Yes, they were the basis of this organization, but this is about all the people who are fighting and nobody cares.”

Every week between fifteen and thirty members of the Colorado Springs Fellowship Church drive to the federal prison in Florence, Colorado to visit their loved ones. “We don’t just want them to have a few visitors,” Rose Banks explains, “We want them to feel like they’re at church, surrounded by the people who love and respect them.”

Every week between fifteen and thirty members of the Colorado Springs Fellowship Church drive to the federal prison in Florence, Colorado to visit their loved ones. “We don’t just want them to have a few visitors,” Rose Banks explains, “We want them to feel like they’re at church, surrounded by the people who love and respect them.”

The IRP-6 aren’t just looking for legal vindication; they persist in the belief that their software can revolutionize law enforcement and they are determined to make it happen. Sam Thurman remembers talking to Steven Cooper, a senior DHS official who was in conversation with IRP over a sixteen-month period, at a Police Chief’s conference shortly before the trial. “He said that when this goes away I’d be happy to sit down with you again.”

Thurman intends to hold Cooper to his promise.