[Cross-posted to Front Porch Republic]

[Cross-posted to Front Porch Republic]There's been some depressing news here in Wichita, Kansas, of late. Not the sort of depressing news that one might typically fear to hear when one speaks about city life: gang violence, police corruption, political graft, etc. (though accusations of all of the above can be found in Wichita, as they can in just about any city). No, the depressing news has all been about projection and perception. Wichita, we've been told lately, isn't where we thought it was, and when one looks at the economic and demographic facts, it doesn't seem to be going anywhere either. No city likes to hear such news (though, honestly, not much of this should be surprising to anyone who has paid attention to the best estimates of our city planners, who have assumed for a while that Wichita's population is likely over the next 20 years to grow at less than 1% a year, and increasing age at the same time).

In particular, the presentations which James Chung, a Wichita native and Harvard-trained economic analysis, laid out in the above articles were pretty unsparing. The city isn't supporting (or is actively driving away) younger people, with the result that the area's oft-proclaimed--though perhaps never really all that actual--culture of entrepreneurialism is disappearing. High-earners are tending to move our of the area and lower-earners tending to move in (many of them, if you dig into the data, older people from small towns throughout south-central Kansas who are coming to Wichita on fixed incomes so as to have greater access to needed health care), with the result that our effective tax base is disappearing too. So much, so sobering. But the most striking comment he made, I think, came when he threw out a line of hope. In speaking of the common denominators shared by those cities (especially mid-sized cities that had to confront the collapse of manufacturing industries) that pulled through challenging times, Chung identified a degree of acceptance: “They put their differences aside. Leaders came together and decided, you know, we are stuck with each other, so let’s (make) this a better city.”

The phrase “we are stuck with each other” is the one which communicates the reality of Wichita, and mid-sized cities in general, most strongly, I think. For my part, it reminds me of a billboard. I've written about this before, but just to reiterate:

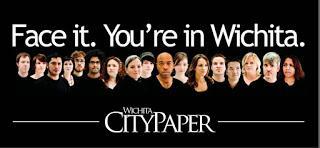

Close to ten years ago, one of our (apparently increasingly rare) local entrepreneurs decided to launch a new publishing venture. It never got very far off the ground, and the advertising campaign for what would have been Wichita City Paper is probably the clearest memory most people have of it. A range of diverse Wichita faces, staring out from a black background, with stark white lettering underneath: “Face it. You’re in Wichita.”

Close to ten years ago, one of our (apparently increasingly rare) local entrepreneurs decided to launch a new publishing venture. It never got very far off the ground, and the advertising campaign for what would have been Wichita City Paper is probably the clearest memory most people have of it. A range of diverse Wichita faces, staring out from a black background, with stark white lettering underneath: “Face it. You’re in Wichita.”That billboard advertisement was wiser than it knew, because it captures an essential truth for cities like Wichita, cities far larger than the hundreds of "micropolitan" urban clusters across the county with a populations of 50,000 or less, but also cities that are not part of an extended metropolitan agglomeration. I mean cities that form their own relatively isolated geographic centers, perhaps topping out at a half-million residents or so. The truth that such cities must face, basically, is that a great many of their residents are regularly tempted to believe that their home isn't what it is, but rather is, or should remain, or is almost ready to become, one of the other two options mentioned above. The truth, of course, is that Wichita and cities like it are not oversized rural towns, supposedly similar in culture and practice to so many of their surrounding and supporting communities. Neither are they, though, on the cusp of a great metropolitan explosion, primed to start networking and contributing to--in terms of jobs, the arts, and more--those flows of information and investment which characterize the great global cities of the world. Wichita, like so many other cities of middling size, is not likely to become a major node in the globalized flow of information, culture, and wealth anytime in the foreseeable future, and it is cannot pretend that its political culture is that of a quaint homogeneous farming village at heart. It is, put simply, a big city--but not all that big; a space of concentrated resources, both human and commercial--but not an ever-expanding supply of such. That's what it is stuck with.

To make a case for sticking with mid-sized cities--for investing in it and improving them--means, first and foremost, facing up to what they are. The odds of being able to quickly create in the context of Wichita's undeniable yet also limited urban character some kind of progressive fantasy of diversity and development are small to nonexistent. With much of the social and economic innovation and opportunity in our country and world invariably gravitating to megapolises wherein the promise of anonymity is entwined with the chance of being able to elide obstacles and break through and do something productive in one new niche or another, leaving older and anxious workers behind, it isn't surprising that Wichita's political culture and economic landscape increasingly reflects, as Chung mentioned regarding Wichita, a "closed" environment. That environment will not suddenly change, and expressing frustration at the lack of diversity or socially oriented initiatives in such cities simply drains energy from what will have to be--as the effort to push Wichita in the direction of reasonable reform in the matter of marijuana possession shows--a long and slow effort.

At the same time, it is even more frustrating to see so many voters and elected officials implicitly endorsing the reverse fantasy, a kind of pastoral-libertarian illusion in which mid-sized cities--which emerged and achieved the fullest success as regional manufacturing hubs--do not need to pay attention to fighting for their place in a globalized arena, but instead should simply chart their own small-government course: in essence claiming the ability to take their ball and go back to the farm. It may be a stretch to look at the current majority on the Sedgwick County Commission and detect an anti-urban bias--but it's not a huge stretch. To make cuts in funding policies which had been developed over the years to serve quality of life purposes in a metro area of over a half-million people in the name of shifting to "cash-only accounting" isn't solely to move in the direction of some kind of "common sense conservatism"; it is also to move against the routine economic practices by which, for better or worse, complex urban bodies have been able to maintain themselves pretty much ever since the Industrial Revolution. It is, in short, to mulishly insist that this particular city needn't be like every other city: it can be smaller, simpler, and not like those other (more liberal) places. To which, again, I can only say: when you've living (as is the case here in Wichita) in the largest single city in the whole state, you have to face the reality that the quaint anarchy of the village town meeting has long since left the barn.

There is something to be said for mid-sized cities, cities that reflect, perhaps exactly because they occupy a kind of middle place in the production and movement of goods and people and ideas, some perspective on how to face up to the challenges of building culturally and economically attractive and rewarding civic spaces today. Wichita could offer that perspective--but only if citizens and leaders alike face up to what we have, and stick with it, rather than wishing it was actually something else. They need to face up to all the civic activity which is happening here, as it is happening so many small and mid-sized cities. Look around our city, as in so many smaller and middling cities, and you can see a great many informal and quasi-formal networks forming: small-scale businesses and volunteer operations and church groups, hosting festivals and art shows and local markets and devotionals, crossing the conceptual boundaries between urban and rural (so much easier to do in a smaller urban space than in a sprawling urban agglomeration!). Of course, few of them present themselves in terms of a "growth plan" to attract venture capital and rent floor space downtown, and neither do they generally start out rejecting all city council seed money on ideological principle. Which means, they get ignored by the fantasists on both sides of the divide.

Wichita--like so many distinct, mid-sized urban outposts across the productive rural heart of the country--needs to be able to grasp the, admittedly, perhaps discomforting "mittelpolitan" nettle: their lot must incorporate certain urban realities (including, most particularly, a stronger and probably more partisan city government, one without the pastoral illusion of neutrality and capable of forcefully expressing an urban agenda, so as to balance out the agenda of the county if necessary) into its vision of itself. This is, I think, unavoidable if terminal decline is to be avoided, and must be faced, accepted, stuck with, even if it is the case that the urbanism such cities are able to generate will probably always--both given their geographic isolation, and given a media environment in which the pace and range of urban expectations primarily reflects the postmodern perspective of the global cities of the world--fail to measure up. That's our dilemma, that's our fate. I hope we face it soon enough.

[An earlier and shorter version of this post appeared in the Wichita Eagle last Sunday.]