Richard Wagner at the piano (1813-1883)

Richard Wagner at the piano (1813-1883)Operatic Odd Couples

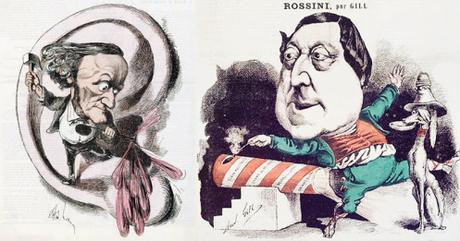

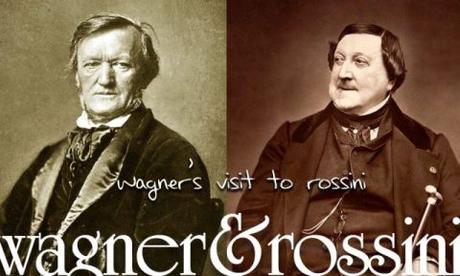

They met in Paris in 1860: the renowned Italian master of opera buffa, Gioachino Rossini, and the fiery German composer Richard Wagner, creator of the “art work of the future.” How did it happen? What did they talk about?

Earlier in his career (in 1822), Rossini had held an audience with the great Ludwig van Beethoven, who counseled him to “make more ‘Barbers’ ” — referring, of course, to his ever-popular comic masterpiece The Barber of Seville. Four years later, while residing in Paris, Rossini quite literally ran into the tubercular Carl Maria von Weber (a cousin to Mozart’s wife, Constanze), nineteenth-century romanticism’s musical “guiding light.” And speaking of Herr Mozart, Rossini even shared musical memories with Wolfgang’s chief rival, Antonio Salieri — the same Antonio Salieri who served as the protagonist of Peter Shaffer’s play, Amadeus.

So what were Wagner and Rossini doing at the time of their historic tête-à-tête?

For one, Rossini had moved to the City of Light in 1824 in order to compose “grander, more serious works,” for which we can thank (or blame, depending upon one’s point of view) his future wife, the Spanish soprano Isabella Colbran. The end result was the four-act spectacular Guillaume Tell, reviewed in a prior post on the occasion of its Metropolitan Opera premiere (see the following link: https://josmarlopes.wordpress.com/2017/07/16/met-opera-round-up-the-seasons-last-gasp-with-guillaume-tell-tristan-and-the-flying-dutchman-part-one/).

Another of his grandiose plans involved an Italian adaptation of Goethe’s Faust, which never came to fruition. We know, too, that after Tell, Rossini wrote no more operas, mostly because he was fed up with having to churn out work after work after work. He was now clearly in a position to live off the fat of the “lamb,” in a manner of speaking, that he himself had fattened through the years.

For another, Wagner had recently put the finishing touches to a monumental opus of his own, the incredibly complex Tristan und Isolde. The paradox of how this work came about has always intrigued me. Let the buyer beware: for the average opera buff, getting into Wagner’s head is an occupation fraught with the greatest of intricacies. The fact is the man was a walking/talking contradiction in terms.

Realizing that, for the moment, his unfinished epic, The Ring of the Nibelung, might not soon see the light of day, Wagner stopped work at the close of Act II of Siegfried. He did not take up the subject again for another twelve years. Now, why on earth would he do that? An over-active imagination, pressing financial needs, and escalating emotional burdens would habitually lead the frantic composer off in pursuit of funds. He would also ease his troubled mind with quixotic dalliances with other men’s wives.

One of these infatuations involved Mathilde Wesendonck, wife of the wealthy silk merchant Otto Wesendonck who paid the tab for the bills that Wagner ran up while the three of them shared living quarters at Otto’s villa in Zurich (don’t ask). On occasion, they were joined by Wagner’s “better” half, his wife Minna. Despite the cozy arrangement, it didn’t take long for Minna to put two and two together and come up with the correct equation: that her husband had been cheating behind her back.

After completing Das Rheingold and Die Walküre, Wagner stumbled upon the philosopher Schopenhauer’s book The World as Will and Idea, from which he extracted a bumper crop of justifications for his newfound worldview. Without going into details — of which there are an endless torrent of essays, pamphlets, writings, and treatises by Wagner himself on subjects as wide-ranging as dismissing Meyerbeer as a hack in “Judaism in Music,” a self-analytical memoir entitled A Communication to My Friends, and a far-flung statement of his ideals in Opera and Drama — suffice it to say the composer glowed red-hot with inspiration for Tristan und Isolde, a story of scorching passions amid an illicit affair (what else?).

Fueled by his liaison with Mathilde, Wagner composed the Wesendonck Lieder (“Art Songs”) based on five of Frau Wesendonck’s poems. Meanwhile, Frau Minna kept pestering him to write a more practical lyric work for the stage, something that would bring their indigent lifestyle some stability and a steady revenue stream. With Wagner, however, nothing was purely “practical” — or “steady,” for that matter. Inventing music that, at the time, seemed vastly unplayable and (even worse) impossible to sing was part-and-parcel to his very being.

There was much more going on than we have room for. Let it be said that departing for Gay Paree was Wagner’s way of seeking his fortune elsewhere. But Paris wasn’t his only stopover point, not by a long shot. During the years 1858 to 1859, Wagner paid manifold visits to such venues as Venice, Zurich, Geneva, and Lucerne.

It’s significant to note as well that Switzerland, while recognized for its persistent neutrality, was the one place where Wagner could plead his case for monetary assistance to the likes of Herr Wesendonck. That would partially explain how the composer was able to get around town. Traveling was never easy for Wagner, even in the best of times, due to his well-founded reputation as a spendthrift and a deadbeat, and his facility for rubbing people the wrong way. He could also be incredibly persuasive, convinced, as Wagner was, of his “superior” intellect and skill at winning people over to his way of thinking.

Back in Venice, the “perfect mood and setting to work on the fatally erotic Tristan” (according to author William Berger), Wagner completed the score for the opera between March and August of 1859. By this point, he and Minna had decided to part ways: she in Dresden, he wherever the need took him. They met again in Paris and, for a brief moment, were reconciled.

In the interim, another love interest laid waiting in the wings. Behind the scenes, Wagner had awakened the youthful yearnings of Cosima Liszt, the homely (!) but overly-admiring daughter of concert pianist and composer Franz Liszt (a notorious ladies’ man in his day). Cosima was recently wed to a brilliant but anxiety-ridden conductor named Hans von Bülow. Both individuals would play significant parts in Wagner’s life and career in the years to come.

Once in the City of Light, Wagner’s decision to conquer Paris eventually brought him in league (and on a collision course) with the Paris Opéra, where plans were finalized for an 1861 revival (in French, naturally) of his earlier Tannhäuser (for the history and background to this stirring piece, see the following link: https://josmarlopes.wordpress.com/2016/03/31/les-pecheurs-de-perles-and-tannhauser-part-two-wagner-bizet-and-performance-practices-then-and-now/).

Clash of the Titans

The differences in approach to Rossini and Wagner, along with their individual working methodologies, were striking. After countless academic studies and tomes analyzing both composers’ oeuvres, we can state, categorically, that Rossini worked principally to fulfill his commissions and nothing more. Whether they were to individual singers or to a particular opera house’s requirements, his personal views toward any single assignment or subject were kept scrupulously out of the finished piece.

Simply put, there wasn’t enough time to devote to extra-musical ideas or theoretical speculations when the pressure was on to quickly bring an operatic piece to the stage. Rapidity of means and swiftness of delivery were the main prerequisites. These were but some of the reasons why Rossini borrowed, for convenience’s sake, from his existing work — by either rearranging and/or reassigning solos numbers and ensemble pieces to fit the needs of a specific situation.

An excellent example would be Il Viaggio a Reims (“The Journey to Rheims”), originally written to commemorate the coronation of King Charles X in France, and which was later reworked as the comic opera, Le Comte Ory.

This was definitely not the case with Wagner whose individual wants took precedent over everyone else’s, including those of his closest acquaintances and benefactors. His frequent crises and scandalous personal life became fodder for any number of operatic plot twists and story lines. You could say that Wagner was his own best dramaturg. Accordingly, it was far easier for researchers to link the worst of his traits to those of his male characters — for example, Wotan, Siegmund, Tristan, and the Dutchman — than it would have been to associate Figaro, Arnold, Mustafà or Tell with any of Rossini’s qualities.

To be honest, neither man was a saint — THAT’S putting it mildly. Signor Rossini was known to have suffered from the effects of gonorrhea (he would soon develop cancer of the colon). But there is no disagreement about Herr Wagner: he was as horrid an individual as they come. Still, once he got to Paris, Wagner made it a point to call on the retired bel canto composer, who had been living in France for over three decades. The visit was arranged by an intermediary, the Belgian music critic and journalist Edmond Michotte, who transcribed their lengthy dialog for later publication.

Since no other methods of preservation existed at the time of the composers’ gathering, we must take what Monsieur Michotte has left us as a valuable document of their converation, but with a healthy grain of salt. Purportedly, one of the pretexts for Wagner’s visit was to set the record straight as to whether or not Rossini had badmouthed him to the press — this from a man who, no matter where he went, had left a long list of insults and offenses in his wake.

“As for despising your music,” Rossini was alleged to have responded, “I ought in the first instance to know it, and to know it I ought to hear it at the theatre, for it is only in the theatre, and not simply by reading the score, that it is possible to render a just judgment of music intended for the stage.” Rossini went on to praise the Tannhäuser March, “which he had found very effective and beautiful. After thus clearing the ground,” Michotte remarked, “intercourse became easy and pleasant, and many interesting topics were broached and discussed during this short visit.”

The subject of Weber and his music had also come up. Beethoven was mentioned, too. “On [Rossini’s] expressing his regret that he had not enjoyed a more thorough training on German lines, Wagner showed his appreciation of what Rossini had accomplished by citing the ‘Scene of the darkness’ in ‘Moses in Egypt,’ that of the conspiracy in ‘Guillaume Tell,’ and, in another order, the ‘Quando Corpus,’ as examples which he could hardly have bettered, and these the veteran [composer] admitted were among the ‘happy moments’ of his career.”

This ad hoc mutual admiration society continued along this vein for some time, until “Wagner spoke of the trouble which the translation of ‘Tannhäuser’ was giving, whereupon Rossini suggested that he should compose an opera on a French libretto, a suggestion which, it is needless to add, did not meet with his acceptance. Then Wagner spoke of his ideals and his expressed desire to get rid of the formalism of opera [a noble thought, one that many composers have articulated throughout the centuries]…”

Interestingly, the Italian master’s reaction was a tad surprising. “Though Rossini was the living embodiment of these conventions, he admitted the absurdity of the ensembles of grand opera, and said that when all the characters formed into line to take part in one, they always reminded him of a band of minstrels, singing to secure a few coppers.”

“It was the custom,” Rossini added, “a concession which we had to make to the public, who otherwise would have shied things at our heads!” You can imagine Wagner’s indignant shock at that admission, but he managed to maintain his composure. “To this Wagner made the obvious answer that, though convention is inevitable, it must be understood in such a fashion as to avoid the excess which leads to absurdities — all that one demands is that a convention, once admitted, should be artistic and consistent in itself.”

Where they disagreed (and most vehemently, or so we are told) was on the subject of the composer as both musician and librettist: “[Wagner] proceeded, sketching his ideas of music-drama, to lay down the axiom that the music and poem [i.e., the libretto] should be so closely knit as to be like the different aspects of a single idea, and this provoked from Rossini the comment that it made it a necessity for the composer to be his own librettist, a condition which he deemed practically insurmountable, but of course Wagner would have none of this, and with great animation urged that the composer should study literature as well as counterpoint.”

They moved on to talk about Guillaume Tell and related matters, until “this memorable interview ended by Rossini expressing his interest in his visitor’s aims, which he had so clearly expressed. For his own part he was too old — ‘being at the age when one is not so much inclined to compose as liable to decompose.’ — to turn his eyes to new horizons, but he was very willing to acknowledge that Wagner’s ideas were of a nature worthy of the serious consideration of young composers. ‘Of all the arts,’ [Rossini] concluded, ‘music is that which is, by reason of its ideal character, most subject to transformations, and to these there can be no bounds. Who, after Mozart, could have foreseen Beethoven? Or, after Gluck, Weber? And, after these, why should there be no end to progress?’”

As the meeting itself had come to an end, Wagner confessed his innermost thoughts to Michotte: “ ‘What would [Rossini] not have produced had he received a thorough musical training; above all, if, less Italian and less skeptic [sic.], he had felt in him the sacred nature of his art? … I must say this: of all the musicians I have met in Paris [which included Daniel Auber, Fromenthal Halévy, Ambroise Thomas, Charles Gounod, et al.] he is the only one who is truly great.’ ”

(End of Part Two)

To be continued….

Copyright © 2017 by Josmar F. Lopes

Advertisements