Renata Tebaldi and her so-called "dimples of steel" (Photo: Decca Records)

Verdi, Puccini...Oh, and Verismo, TooWith Callas' rise, the bel canto revival movement took off as never before. Historically, that same resurgence had already begun, what with post-World War II reconstruction of many of Italy's opera houses - some of which had been damaged during the worst of the era's aerial bombardments - along with the renewed interest shared by the country's major conductors.

We can thank such farsighted figures as Messrs. Vittorio Gui, Tullio Serafin, Antonino Votto, Gianandrea Gavazzeni, Mario Rossi, and later Carlo Maria Giulini and Claudio Abbado (to also include the scholarly insights of Australian-born Richard Bonynge) for leading the charge in this fruitful, albeit belated direction. Still, without the requisite artists available to give bel canto the impetus it so richly deserved, there would be no "revival" as such.

Given the challenges required to bring this unique art form back from its premature demise, readers can sit back and marvel at the sheer breadth and beauty of such previously neglected works as Rossini's La Cenerentola, L'Italiana in Algeri, Il Turco in Italia, Il Signor Bruschino, La Gazza Ladra, Mosè in Egitto, and, of course, that grandest of all grand operas, the massively constructed Guglielmo Tell.

Added to these were the unearthing of such treasures as Donizetti's Lucrezia Borgia, the complete version of Lucia di Lammermoor, the so-termed "Tudor Trilogy" of Anna Bolena, Maria Stuarda, and Roberto Devereux, and the French-language adaptation of La Favorita. Alongside which, Bellini's output remained at the heart of the restoration effort, what with Callas' participation in Norma and La Sonnambula, in addition to periodic forays into I Puritani and Il Pirata, works that demanded the full gamut of vocal and histrionic accomplishment.

In all, the difficulty of doing operatic justice to such refined material as these rested solely with the singers. Besides La Divina, audiences were indeed fortunate to have heard the likes of sopranos Margherita Carosio, Lina Pagliughi, and Pia Tassinari, mezzos Ebe Stignani, Giulietta Simionato, and Fedora Barbieri, tenors Tito Schipa, Ferruccio Tagliavini, Mario Filippeschi, and Giuseppe Di Stefano, baritones Gino Bechi, Tito Gobbi, Renato Capecchi, and Sesto Bruscantini, and basses Italo Tajo, Giulio Neri, Nicola Zaccaria, and Nicola Rossi-Lemeni, among others, in both live and recorded interpretations of the above oeuvres.

What of early-period Verdi, or the best of what Puccini had to offer? How about untapped material from the recently mined verismo repertoire? Surely Callas wasn't the only artist around to have wandered into this still-fertile field.

For that, listeners can wallow in the beauty, refulgence, and emotionally charged artistry of Italian diva Renata Tebaldi. Dubbed by many as the "cream of the vocal crop," Tebaldi was an exact contemporary of the previously discussed Maria Callas (see the link to Part One: https://josmarlopes.wordpress.com/2023/12/09/they-lived-for-their-art-the-first-ladies-of-opera-callas-tebaldi-and-milanov-part-one/) .

At the time - specifically, from the 1940s to about the late 1960s - Tebaldi and Callas' basic repertory had overlapped to a minor extent, which makes comparisons to these widely divergent singers that much more compelling, if not altogether challenging.

Tebaldi, Rudolf Bing, and Callas at Met premiere of 'Adriana Lecouvreur ' (Photo: Met Archives)

First of all, let me get this off my chest: I love and treasure both of these fine artists. In my record-collecting and/or listening experiences, I've had the unique opportunity to hear many if not all of their officially released recordings, in addition to quite a few live performances, along with YouTube extracts and other sources.

To say that I favor one artist over the other is unfair, in that and in terms of their vocal resources and repertoire I have grown to admire and appreciate their differences as much as their similarities.

With regard to repertoire, both singers signed recording contracts with the period's major labels: Callas at EMI-Odeon/Angel, and Tebaldi at Decca/London. Private or pirated examples of their art can also be found, some of which favored offbeat material.

In the Beginning...There Were InfluencesThe course of female vocal artistry, in particular that of the spinto ("pushed up") and/or lirico spinto varieties, can be traced back to the turn of the last century and all the way up through both worldwide conflicts.

From there, one need only catalogue the vast array of native Italians, among them the glamorous Lina Cavalieri (a personal favorite of Puccini's), Rosina Storchio (the first Madama Butterfly), Gilda Dalla Rizza, Mafalda Favero, and the ageless Magda Olivero. Of course, no discourse concerning soprano vocal quality could possibly be complete without mentioning the incredibly compelling figure of Claudia Muzio.

Golden Age Diva, Italian soprano Claudia Muzio (Photo: Wikipedia)

Both Callas and Tebaldi have been compared, at separate intervals, to the short-lived Ms. Muzio, mainly for that artist's unique ability at expressing the pain of existence with a voice drenched in pure suffering, in between the sighs and whispers of one who knew, instinctively, that her time on this earth was limited. As to whether Muzio influenced Callas more so than Tebaldi... well, then, that's a debate for the experts!

There were other artists of equal stature, of course, whom writers and critics often cite as having been instrumental to Callas and Tebaldi's development. Of these, the highly volatile Paduan-born Lina Bruna Rasa, as Santuzza in Mascagni's Cavalleria Rusticana, bears listening to (her portrayal, under Mascagni's baton, reminds one of an untamed stallion); as does the dramatic soprano dynamism of Celestina Boninsegna, or the later Caterina Mancini, in anything by Verdi; or even the Italian-American Dusolina Giannini - all of whom were instructive in their individual ways.

As for Tebaldi herself, serious vocal studies ultimately took place at the Conservatory in Pesaro, under the wing of verismo specialist Carmen Melis. This proved especially significant in tailoring the young aspirant's natural inclination toward works by early- to late-period Verdi, as well as practically all of Puccini's output, not to mention individual contributions by Ponchielli, Boito, Giordano, Mascagni, Leoncavallo, Cilèa, Refice, and others.

Born in Pesaro, Italy, on February 1, 1922, Renata Ersilia Clotilde Tebaldi, like her contemporary Callas, grew up in a divided home, with her father (a cellist by profession) and mother having separated early on, possibly from an illicit affair before Renata was even born. Tebaldi's mother and grandmother raised her at that point.

A survivor of an early bout with poliomyelitis, the youngish Renata took to singing in her church's choir. This led to more structured vocal studies with different tutors and teachers at different times (i.e., the previously mentioned Melis, among others) and at regular intervals, culminating in an eventual 1944 debut as Helen of Troy (Elena) in Boito's Mefistofele in the city of Rovigo.

It did not take long before the ambitious novice came to the attention of another former cellist and discerning musician, Arturo Toscanini. The notoriously commanding "Maestro," as he was called, can be quoted as having labeled young Tebaldi with possessing "the voice of an angel," many decades before Welsh artist Charlotte Church could claim the honor. Tebaldi's earliest forays in Parma, Toscanini's hometown, resulted in her appearance in works by Puccini (Mimì in La Bohème), Mascagni (Suzel in L' Amico Fritz), Giordano (Maddalena in Andrea Chénier), and others.

Moving on to Teatro alla Scala, in Milan, and other European opera centers, Tebaldi's creamery-butter tone, house-enveloping personality, tallish big-boned figure (like Callas, Renata stood head and shoulders above her leading men), and charmingly dimpled cheeks(!) conquered many a skeptical critic, which despite a somewhat stiff stage deportment made her a favorite among the paying public.

Her North American debut occurred at San Francisco's War Memorial Opera House as Verdi's Aida around 1950; while her initial Metropolitan Opera appearance took place on January 31, 1955, as the most feminine and genteel of Desdemonas in the same composer's Otello. Her partner for that occasion was the leonine tenor Mario Del Monaco.

The Sound of SolaceI first heard of Tebaldi on or about the late 1960s. There was so much talk on the radio and in the newspapers regarding her undertaking the flamboyant part of actress Adriana Lecouvreur in Francesco Cilèa's similarly titled work that I simply had to tune in to see what all the fuss was about.

Listening to the WQXR-FM broadcast of the opera, I was bowled over not only by Tebaldi's enveloping characterization and flirtatious manner, but by the fullness with which she hurled that marvelously seductive sound into the Met Opera auditorium. "My goodness," I thought to myself. "What tenor could possibly withstand such an assault?"

Well, my concerns were quickly put to rest, as I also heard, for the very first time in my listening experience, the mammoth-sounding roar of one Franco Corelli. Standing a shade or two over six feet, the rolling thunder that poured out of Corelli's throat was met, note for note, by his attractive leading lady: the stunningly beautiful Tebaldi, in powdered wig and lace gown. I wasted no time in recording their Act One repartee, which (if memory serves) I was able to capture on a small open-reel tape machine - the first among many live performances preserved for my subsequent listening pleasure.

At about the same period, my dad, who readers of this blog surely recall as having been a die-hard opera fan, told me about a film version of Verdi's Aida that was playing at a downtown movie theater. At the time, I was obsessed with this opera, having already recorded the complete Second Act from a live radio performance of the work (that featured Leontyne Price, James McCracken, and Robert Merrill in the leads).

Upon witnessing this Italian-made production, I must confess that I had little to no knowledge of what opera would be like on film or in the theater. The one thing that caught my eye was that the "singers" (mostly actors in dark makeup or flowing robes and wigs) had barely parted their lips, whereupon the most overwhelming noise still poured out. "That's odd," I remember thinking to myself. "So much sound, for so little effort. That can't be right!"

Instead of Tebaldi as the enslaved princess Aida, there rose the robust visage of Sophia Loren - curvaceous form and all! Instead of mezzo-soprano Ebe Stignani, a pre- and postwar star of the Rome Opera, as her rival Amneris, there went Lois Maxwell. Most James Bond fans may recall Ms. Maxwell as the person who played Miss Moneypenny to Sean Connery's 007. I was shaken, if not stirred by all this. And so on, and so forth. So this is opera? What a disappointment!

To be perfectly honest, I was not in the least disturbed by the soundtrack. The "acting," by turns amateurish and effortful, via these non-singing substitutes, was...well, appalling, as one might infer. But those voices! Ah, those voices! Now you're talking!

Tebaldi's sound, in deluxe quadraphonic stereo, literally filled the auditorium. The voice was so lush, so vibrant, that I became an instant fan. But the best singing of all came from the Amonasro. Portrayed by veteran baritone Afro Poli (who also played Scarpia in another Italian-made production of Puccini's Tosca), that snarling rasp of a voice belonged to the impressive Gino Bechi. The final farewell to life, where both Aida and her lover Radames (sung by winsome tenor Giuseppe Campora) are entombed forever and a day, raised the rafters with their bawling and bellowing. No wonder they died a slow death! Lights out.

My feeling was that Master Verdi would be rolling in his grave if he had witnessed and heard what had been done to his grand opera. Still, how thrilling, how enticing, how positively overwhelming these big voices seemed to my teenaged ears. I simply had to buy a recording of the complete opera, no matter what. So out I went, looking in all directions for the next available record shop.

At the time, the only ones in my Bronx neighborhood were discount department store E.J. Korvette's and a Sam Goody or two somewhere in midtown Manhattan. I had already invested in a budget version of Tebaldi's first Tosca, a monophonic recording with our friend Signor Campora as her lover Cavaradossi and Italian baritone Enzo Mascherini as a slightly over-the-hill Scarpia. Would Tebaldi's stereo remake of Aida be up for sale? The one with Bergonzi, Simionato, MacNeil, and Herbert von Karajan presiding? Wow, that would have been awesome! Not a chance.

Another choice would have been Callas' EMI/Angel version, with Richard Tucker and Gobbi, Serafin conducting. Nah, that wasn't available either. Instead, I settled for the old RCA Victor edition with Zinka Milanov, Jussi Bjoerling, Leonard Warren, and Fedora Barbieri. Not a "bad" choice by any means, and one I will devote more time to when the discussion turns to Madame Milanov herself.

'The Girl' and the Setting SunFor a sampler of Tebaldi's art, there are dozens of recital albums to choose from - both for online download and on multiple platforms. All are pleasing to the ears, which remain prime examples of the singer's career accomplishments: that lush, full-toned, voluminous outpouring only Donna Renata could provide.

This was just one of her many attributes. Never known as a compelling stage figure or a particularly commanding one, Tebaldi nevertheless poured her heart and soul into endeavors that many felt went beyond what they had formerly thought of her acting abilities.

They would help to save what came next.

With that said, Tebaldi experienced a major vocal crisis sometime around the middle to late 1960s. Some have attributed this decline to the earlier passing of her beloved mother, a terrible moment for any person but more so for such an emotionally attached artist as herself.

Added to which, Tebaldi's assumption of the lead role in Ponchielli's La Gioconda, a torture test for even the finest of performers, exposed the singer's late-career limitations, among them a hardening of her middle voice, difficulty with pianissimo passages, and squally unfocused top notes. Still, the deluxe 1967 Decca/London recording of Gioconda, while well-received by most reviewers, displayed different aspects of her art. For instance, her acting in this and other assignments - always an issue in the past - had undergone a miraculous transformation.

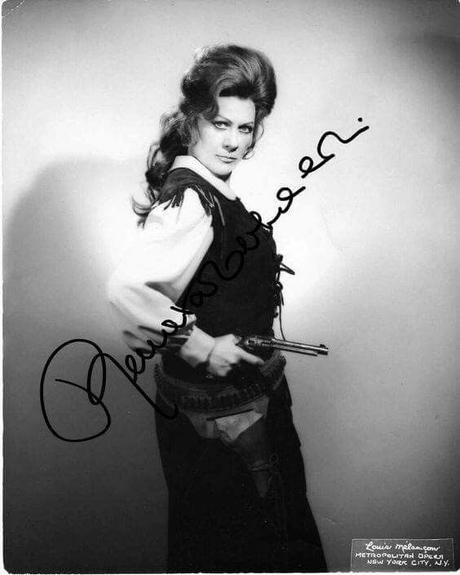

Incredibly, as the voice began to age or "deteriorate" (in many people's minds, it never recovered its former luster), Tebaldi's ability to convey character, especially that of the pistol-packing Minnie in La Fanciulla del West, remained one of her best if not the best aspect of her interpretation from among the short list of performing artists willing to expose themselves to this torturous assignment.

Tebaldi as Minnie, in Puccini's 'La Fanciulla del West' (Photo: Louis Melancon)

If I hadn't heard the broadcast myself, I would have had a hard time believing it. The Act II confrontation between the "Girl," Minnie, and the rough-and-ready Sheriff Jack Rance (a snarling, mustache-twirling Anselmo Colzani, who substituted for an indisposed Cornell MacNeil) has become part of Met Opera legend. Far from the best-sounding version - after all, this was a live radio broadcast - we can state, with absolute certainty, that the hair-raising "game of chance" sequence will have audiophiles on the edge of their seats.

Listen to how the incessant drumbeat reflects the emotional heart-pounding situation surrounding both Minnie and Rance (THAT was Puccini's doing), as the participants square off in a life-or-death round of poker - all of which to save Minnie's bandit boyfriend from hanging. Audiences will relish the fact that our heroine's situation, reminiscent of an episode from the silent serial The Perils of Pauline, will resolve itself via her slipping the winning hand into her stocking.

When the last round of cards is dealt, the orchestra blasts out a thunderous fortissimo, as Minnie pretends to faint. She orders Rance to fetch her some water. In the interim, Minnie takes out the cards and replaces them with the winning ones. Of course, Rance suspects that dirty work is afoot - he's no fool. But that wise old saying, "There's no fool like an old fool," rings especially true where Rance is concerned. As he himself is "stuck" on the Girl, the Sheriff purposely lets Minnie win the round and keep her wounded beau, the bandit Ramerrez.

Still believing he can outsmart her, Rance rages that he's won her at last. "That's what you think!" Minnie slams the winning hand onto the table and cries out the immortal line for all it's worth: "Three aces and a pair!" (in Italian, "Tre assi e un paio!"). The live audience went wild with shouts and bravos, so much so that they drowned out what came after: one could barely make out Rance's exit line, "Buona notte!" ("Good night!").

With Minnie's uncontrollable hysterics in the air at having duped her foe - Tebaldi's wildly off-pitch warbling notwithstanding - the curtain fell to riotous applause. The ovations lasted well after the act's conclusion. And the panelists at the intermission's Opera Quiz were STILL talking about it many minutes later! Tebaldi had raised the "wow" factor up to 11.

On a trivia note, Callas had been tapped to record La Fanciulla with Corelli and Gobbi, but situations and crises being what they are, this event never came to pass. The final Angel/EMI edition of Puccini's sagebrush saga was finally issued with Birgit Nilsson as the Girl (a role she never, ever sang on the stage!) and only minor artists in support. Whereas Tebaldi's officially recorded Decca/London take from 1958 featured frequent costar Mario Del Monaco and the redoubtable "Big Mac" MacNeil. At that point, she had not yet assumed the role on the stage. In this writer's opinion, the wait was well worth it.

Tebaldi never married, although she hinted at many loves in her life. According to some wags (either Met Opera General Manager Rudolf Bing or archivist Francis Robinson, depending on whose memoirs you consult), "Those dimples were made of steel." As far as that rivalry between her and Ms. Callas, well... Surely, there were prickly encounters in their past, but all of that alleged "bile" transformed into sweetwater under the bridge. In fact, the two divas expressed a mutual admiration for one another's artistry, if somewhat forced.

Tebaldi retired from the opera stage in 1973, at age 51, performing Desdemona at the Met one last time, the role of her 1955 debut there. Renata Tebaldi passed away at 82, in her home in Milan, on December 19, 2004. But her voice and legacy continue to live on.

Renata Tebaldi: Recommended Recordings- Adriana Lecouvreur (Del Monaco, Simionato, Fioravanti - Capuana) Decca/London

- Aida (Simionato, Bergonzi, MacNeil, Van Mill, Corena - Von Karajan) Decca/London

- Andrea Chénier (Del Monaco, Bastianini, De Palma - Gavazzeni) Decca/London

- Un Ballo in Maschera (Donath, Resnik, Pavarotti, Milnes - Bartoletti) Decca/London

- La Bohème (D'Angelo, Bergonzi, Bastianini, Siepi, Corena - Serafin) Decca/London

- La Fanciulla de West (Del Monaco, MacNeil, Tozzi, De Palma - Capuana) Decca/London

- Madama Butterfly (Cossotto, Bergonzi, Sordello - Serafin) Decca/London

- Manon Lescaut (Del Monaco, De Palma, Borriello - Molinari-Pradelli) Decca/London

- Otello (Del Monaco, Protti, Romanato, Corena - Von Karajan) Decca/London

- Turandot (Nilsson, Bjoerling, Tozzi, Sereni - Leinsdorf) RCA Victor

(To be continued....)

Copyright © 2024 by Josmar F. Lopes