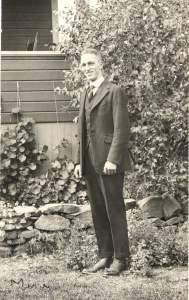

Mervyn Stephenson, ca. 1920s.

[Part 2 of our examination of the life of Mervyn Stephenson, Linus Pauling’s cousin.]

Having completed his schooling in 1919, Mervyn Stephenson was quickly hired by Conde B. McCullough, a former college professor known today as Oregon’s most famous bridge engineer. Excited to begin his career, Stephenson moved to southern Oregon shortly after graduation to work as a civil engineer for the Bridge Division of the Oregon Department of Transportation. The first project that he worked on was in Douglas County, but the project was shut down so he returned to Salem to delve into bridge design. Mervyn worked hard, but he still found time for fun and was especially keen on dancing: he attended dance halls on the weekends and saved several of his dance cards to prove it.

At work, Mervyn wasn’t stuck behind a desk for long. One of his first major projects was the building of a concrete arch bridge over Hog Canyon in 1920. In 1921 he worked on the Crooked River Bridge in Prineville, as well as the dam for the Prineville Reservoir, and the Bear Creek Bridge. A year later he assisted with repairing the John Day Highway. It was here that he helped to rehabilitate a stone building that had been the headquarters of a Chinese doctor, Kam Wah Chung, a structure that was transformed into a museum many years later.

The Kam Wah Chung & Co. Museum, Grant County, Oregon.

As time passed and his skills became more widely known, Mervyn was offered a job in highway construction in Cuba, but he turned it down, preferring to stay close to home. The Federal Bureau of Public Roads also offered him a job in 1933, but he did not accept, choosing to stay with Conde McCullough instead. In the years that followed, he was a member of the teams that designed and built several of the iconic structures now closely associated with McCullough. These included the Coos Bay Bridge, Rogue River Bridge, Siuslaw River Bridge, Yaquina Bay Bridge, John Day Bridge and other coastal bridges. In an interview published in the January 17, 1934 Marshfield/Coos Bay Times, titled “Bridge Program Hailed as Major Step in Progress,” Stephenson lent insight into what it was like to work for the famed engineer.

We used to have a lot of fun. [McCullough would] come to look at what you were doing. [He’d] look over your desk and see what you were designing and he’d always reach over and get your pencil and start scribbling, stick [the pencil] in his pocket and walk off. So after we got to know him better, as he’d start to move, we’d reach over and grab [the pencil] out of his pocket, never said anything, just reach over and grab it out of his pocket.

Conde McCullough, ca. 1920s.

The Second World War was a source of new opportunities for Stephenson. In 1945 the U.S. Army contacted him asking him to do some highly secretive work overseas in support of the war effort. Stephenson traveled to Washington D.C. for a briefing and then was flown to the Hickam Field base near Honolulu. As Stephenson soon learned, the Army had sought out and gathered civilian scientists and engineers to help plan the U.S. invasion of Japan, and Stephenson was one of the experts called in to assist. As such, he was instated as a colonel and assigned a high pay grade because of his specialized skill set.

While at Hickam Field, Mervyn studied maps and aerial photos, analyzing the roads and bridges that might be encountered in the planned invasion. He also helped to estimate the amount of raw material needed to build bridges and highways as U.S. forces moved across Japan. This work never came to fruition, due to the Japanese surrender on September 2, 1945.

Still of use to the Army, Stephenson was transferred to a unit working on the Philippines Highway Planning Mission and charged with rehabilitating the country’s highway system. For a while he moved with his unit through Japan and the Philippines, inspecting tunnels and bridges. Once this mission was completed, he returned to civilian life as an Assistant Bridge Engineer with the Oregon State Highway Department.

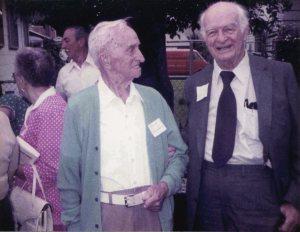

P.M. Stephenson and Linus Pauling at a Darling family reunion, 1983.

From 1955 to 1957, Stephenson was the Oregon State Bridge Engineer. Most of the bridge projects that he oversaw, including Winchester Bridge and the Fords Bridge, resided on I-5, the west coast’s main interstate highway. Probably the most important project that Stephenson supervised was the design and construction preparation for significant upgrades to the Columbia River Interstate Bridge, linking Portland, Oregon and Vancouver, Washington. He retired from employment with the Oregon State Highway Department in 1957, but was soon appointed, by the governor, to the State Parks and Recreation Advisory Committee.

After his retirement, Stephenson and his wife traveled extensively, their favorite destination being Mexico, which they visited several times during the 1960s and 1970s. In 1972 Linus Pauling sent his cousin a letter, asking about the arrowhead collection that Mervyn had inherited from their grandfather Darling. He also took the opportunity to provide Stephenson with an update on his life and burgeoning interest in Vitamin C, and asked that Mervyn and his wife visit him and Ava Helen in California on their next trip to Mexico. This letter is the final record of written contact between Pauling and Stephenson, though we know from photographs that the two saw one another at least one more time, at a Darling family reunion held not long before Mervyn died.

Philip Mervyn Stephenson passed away in Salem, Oregon in 1983. His undated autobiographical manuscript ends with various accounts of his travels in retirement. The piece makes little mention of Linus Pauling, save for the memories that the two shared in their childhood and college years. Though we can’t know for sure, it is likely that the two young boys who held much in common as they hunted for small critters, searched for arrowheads and caused mischief in their fathers’ stores, gradually grew in separate directions as they pursued their passions and careers with tenacity.