Day three of this extra, extra special Meet series, sees Dilman

Dila talk about his novella The Flying Man of Stone and the characters such as Luanda Magere from folklore of the Luo people that the title comes from. Dilma also gets candid about the ways in which the 'fragile peace' in Uganda and his

experiences of racial abuse during his time in Nepal fed into the writing of

the story.

Day three of this extra, extra special Meet series, sees Dilman

Dila talk about his novella The Flying Man of Stone and the characters such as Luanda Magere from folklore of the Luo people that the title comes from. Dilma also gets candid about the ways in which the 'fragile peace' in Uganda and his

experiences of racial abuse during his time in Nepal fed into the writing of

the story.

Dilman Dila is a writer and filmmaker. He recently published a collection of short speculative stories, A Killing in the Sun. His works have been honoured in many international and prestigious prizes. Enjoy!

I found violence (in different shapes and forms) to be a recurring theme in this anthology, but The Flying Man of Stone I found the most violent. One scene actually caught me by surprise - when teacher struck the missionary in the village. Could you reflect on the theme of violence in the story? I set out to write a war story, and thus it had to have a bit of violence in it, partly as a plot device. The radicals needed a motivation. The teacher needed something to justify his ideology, and his followers needed something more than just rhetoric to follow him. The superhero and the teacher believe violence is the only way to stop violence. You are not the first to mention it. I’ve seen it in a few other reviews, and I was surprised the first time I saw that comment. I couldn’t help asking myself, ‘Really? Is there too much violence or are readers being too sensitive?’ I did not even think of it as a theme for the story. I wanted it to be a simple father-son story, in which a father helps his son become a superhero. But after I wrote the first scene I knew it was going to be a father-son superhero war story.

That first scene, of a family fleeing from fighting, has plagued me for many years. I’ve had nightmares about it, with one question troubling me ever since I was a little child: ‘What if I find myself fleeing as a refugee?’ This nightmare I think comes from the trauma of growing up in a fragile peace.

In the ‘80s, there were various civil wars in Uganda. My town was so far from any of it that we only heard about it in rumors, and we only saw it from the occasional convoys of military vehicles that sped through the streets, with soldiers perched atop lorries singing about how they were going to fight. Our parents and teachers never tired telling us not to play with strange objects, and we heard stories of children who picked up strange metals, only for it to explode and they lost their limbs, or lives. We used to play a lot of war games, but mostly inspired by Vietnam War movies, and by action films like Rambo. The stadium in our town, with its overgrown hedge fence that was the closest thing we had to a jungle, was our favorite playground. One day, I stayed at home to wash dishes after lunch, but other kids were playing when one of them burst out of the fence with a real gun, an AK47. Lucky there were adults in the pavilion playing cards (gambling) and they took it away and gave it to the police. In ’86, when Museveni’s rebels took over power, that’s the closest I came to witness soldiers in action. Not their fighting. But we kept picking up bullet shells in the streets and playing with them, and some of what I’ve witnessed remains imprinted in my mind forever: civilians attacking a soldier and disarming him; a soldier returning home after a looting spree, a long line of people in front of him carrying the loot, as the soldier keeps shooting into the air and swigging from a bottle of beer. Later when I saw depictions of the slave trade, I kept thinking of that soldier and his line of captives carrying his loot.

We allegedly have been at peace since 1986, with regular elections. However, every time there is an election, the predominant issue is not jobs, or the economy, or health care, but whether there will be chaos and violence. In earlier elections, the ruling candidate Museveni had radio adverts with war scenes in them, driving home a clear message. Those kinds of adverts are no longer played, but his speech threats have always been the same: ‘Vote for me or there will be a war.’ For this to dominate a country’s elections says a lot about the fragility of peace in that country, which is worsened by a leader who won’t leave power, and who is such a darling of the US and UK that while in public they condemn him, they support him with economic and military aid.

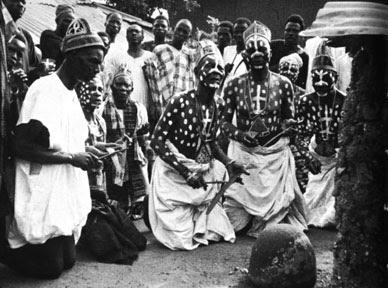

This is the second war story I have published, but it’s the first to talk about a war breaking out after a failed election. I guess it betrays my fears, and my feelings of helplessness at the hands of corrupt leaders and their international allies who do anything to stay in power. The Flying Man of Stone is also about colonialism, and really what got left behind. While there is a war going on in this unnamed country, I am quite interested in the internal conflict going on with the villagers particularly around indigenous faiths vs. Christianity and Islam - which is probably as devastating as the war itself. Could you speak to the theme of identity post-colonialism in the story? The theme of identity in contemporary Africa is something everyone in Africa struggles with. Uganda for example is largely Christian, with a Muslim minority. Religion has never been a major factor in our politics. It happened in the 1800s in Buganda kingdom, but has hardly featured in politics after independence. Maybe it is because a vast majority of both Christians and Muslims still practice ancestral spirit worship (in secret), and so that unites them with a bond they cannot acknowledge in public. In public, they proclaim to be either Christian (80%) or Muslim (12%), but this does not of course reflect their true religious identity, which is in the vague area between fully accepting foreign religions and still clinging on to ancestral norms.

From African Shamans and Ancient Shrines

Most homesteads in rural areas will have a shrine dedicated to the ancestors, and many individuals consult shamans for blessings in all aspects of their lives. It is common to see people with charms, to see babies with ritual beads around their waists even as these babies are being baptised in church. The President, whose family is born-again, and has championed the rise of Pentecostalism in the country, has publicly sought the support of shamans, who in 2001 gathered at Nakivubo stadium to bless his campaigns. There are talks of politicians who, upon being elected, won’t enter office until after a shaman has performed certain rituals to cleanse the office of the previous office bearer’s charms. I think it’s only a matter of time, and a matter of the right factors happening, before we see people going to worship openly in shrines the way Christians and Muslims go to churches and mosques. I heard a few years back of shamans who started to wed people in shrines, and encourage them not to go to churches. But I also think that there will be a marriage of foreign and indigenous faiths as people pick the best in both. This is already happening in some nations within Ugandan, where people have abandoned Christian names like John, Peter, Mary, and instead directly translated African names into English words (to comply with Christian teachings and norms, I suppose) and so you find people called ‘Grace’ ‘Praise’ ‘Flower’ ‘Happy’ ‘Patience’. So a person called ‘Kwikiriza’ which could have been an indigenous name to say someone has faith in an ancestor or the other, becomes ‘Faith’, and is interpreted to mean someone has faith in the Christian God. When people first learn my name, the first question they ask is; ‘Where are you from?’ They cannot place me in any of the national groupings in Uganda. I grew up in at the border of Uganda and Kenya. One small town about only six kilometres away from my home that had one side of the street in Uganda and the other side in Kenya. People of that town never know which country they belong too. My father is from the Western region, my mother from the North, but I grew up in the East, and so I consider myself as one from the East, but this only adds to the confusion of my identity. When people first see me, they assume I am from the North, then they look at my full names, and they see I have a mixture of Northern and Western names. The last time I went to get a passport, the immigration officers wouldn’t give it to me until I had to bring my father to them to prove I was a Ugandan.There’s also an ancient alien race, new technology and their relationship with humans - could you talk more about this relationship? It’s not really an ‘alien’ race. I wonder why people keep seeing them as ‘alien’. Maybe because we have been conditioned to believe that we are the only intelligent species to have ever walked on this planet, and so any other intelligent beings have to be from outer space. But what do we really know about the history of Earth? What do we know about beings that lived here ten thousand years ago? Just because we have not found their fossils doesn’t mean they did not exist.

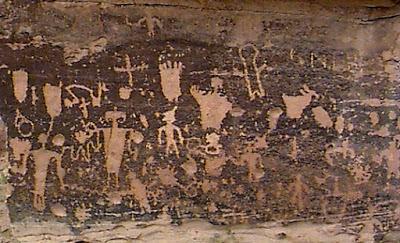

We know about ancient Egyptians and the Mayans and the Sumerians because our civilisations sprung from theirs, but what about those structures we cannot explain, like the Stonehenge and the Nazca Lines? How do we know there were/are no other intelligent species that went extinct, maybe as a result of human expansion and migration? All over eastern Uganda, there are strange rock formations. You look at some and you think it imitates a shape that you know. There has been little study of these rocks (apart from the famous stone musical instruments in Dolwe Island, Lake Victoria, that survive till today), which are dismissed as works of nature. Yet folklore in some communities talk about how these rocks have life, how they move in the night and return to their spots in the day. These rocks make me think that maybe there was a species long before us who fashioned them. Maybe this/these species was so intelligent that they did not need metal and fuel the way we do. That’s why Kera’s father only tells him those creatures are not spirits, but an ancient being. Not aliens. :-)

Ancient Star Beings of the Hopi

What’s their relationship with humans? None, I should think. They live in the darkness. When we think of life, we think of light, and we think there can be no life where there is no light. But these creatures live in the darkness, and light hurts them. Maybe the people who live near the valley see signs of them every once in a while, and believe them to be spirits, so they worship them. I think if we came upon another intelligent species, and there is no sign of their spaceship, we might mistake them for spirits. They, on the other hand, are only concerned about keeping the light out of their caves, so when they come into contact with humans, they turn humans into slaves to make this happen. In later works I might explore more in depth into these creatures, but for now I don’t know much about them :-).This is also a superhero story (but in a different way to The Last Pantheon) and Kera is quite an unlikely hero. What was the reason behind placing so much power and responsibility in the hands of a teenage boy? I see this more as a father-son story dealing with the death of their beloved ones. Maybe I was trying to purge the demons that bothered me in my childhood, as stated above, about the recurrent nightmare where I find myself a refugee because of war, all alone without family. Kera’s father doesn’t have long to live, and after he goes Kera will need a family, unless he can rescue his brother from captivity, so he gives Kera a flying machine and a long range gun. I did not really want to make Kera into a superhero, his only mission was to rescue his brother, and then surrender the weapon, but like any boy who finds himself with powerful toys, Kera gets other ideas. While writing this story, I discovered I don’t like superheroes, not just because there’s always a thin line between a hero and villain. There’s something wrong with the concept that only one person can save the world. That is a childish concept.

I wrote this story upon request from Ivor, after he had read two other stories in my book ‘A Killing in the Sun’. The two stories were ‘A Wife and a Slave’ and ‘Lights on Water’. He wanted me to write something about that world, but it’s a dark world, where Africa is mono-racial and a very evil force rules. It’s not a world I love at all. I don’t even like writing about it for it drains my emotions.

I lived in Nepal for two years, where I experienced racial abuse for the first time in my life, where I was called a dog, a ghost, and where mothers told their children that I would eat them even as I watched, and I think that experience gave birth to these stories, as I struggle to make sense of the question of race. Ivor urged me to write about it. His argument was simple. It’s the same anyone who writes dystopian scifi gives: Humans need warnings. In Nepal, I coped with what I was facing by rationalising things. I looked at it from their point of view, saying it was a case of first contact and these people were meeting a black person for the first time after centuries of two things; 1) in Hindu mythology demons are black, and 2) colonialism taught them to look down upon dark skins. I had to come up with this line of thinking to forgive, but I couldn’t take away the trauma. All three stories in this world are set in Africa, where many real-world events give us a cause to worry, including the expulsion of Asians from Uganda in the 1970s, the attack on white farmers in Zimbabwe, and xenophobia in South Africa. Many socio-political and economic factors influenced these unfortunate events, and the big question is; Will it happen again, or will something worse happen? What can prevent it? I have no answers. I can only provide a scenario of how it might unfold, and of what might happen if we do nothing about it.

Which brings me back to the question of superheroes. Humanity is forever faced with the threat of descending into darkness. Any moment, any human society can slip over the edge. And who can stop this from happening? Superheroes? I would say yes, if pop culture did not place all the responsibility on one individual. The classic superheroes, like Hercules, never worked alone. Hercules accomplished his tasks with the help of a team. He was merely their leader. The two [characters] who lend the story its title are Luanda Magere and Kibuuka. Magerere, a man of stone, he was invincible in battle, but he always fought with the Luo army by his side, and Kibuuka, a man who could fly and shoot arrows from the sky, never went to war without the support of the Buganda army.

Illustration of Luanda Magere: The Warrior of Stone

So why are superheroes today often lone individuals, with only one or two people to support them? Very rarely do we see teams, though Hollywood has started to play with that concept, very rarely do we see an army, or a community, coming together to put an end to an injustice. It often is a lone hero who no one believes in, who no one supports, until the end when s/he defeats evil, then the community comes out to cheer. But why? Is this because pop culture is heavily influenced by Christianity, and so it borrows from the concept of a rejected God (Jesus) sacrificing himself to save the whole world? Is it a capitalist thing that champions the individual over the community? Maybe A Flying Man of Stone is a mockery of superheroes, maybe what I was trying to say is that no one person, whoever s/he is, whatever weapons s/he has, whatever capabilities s/he has, no one person can save humanity without community support. Maybe that’s why I made the superhero a weepy teenage boy.Final question (which I’m asking everyone) what’s next? I finished the first draft of a novel (‘The Thing in Her Dream’) a few days back, so I’ll be working on that for most of this year. It explores the dream theory that the universe is a dream. It’s about a scientist who invents a machine that can broadcast dreams, but his test subject, a woman experiencing severe violence from her husband, is sucked into one of her own dreams, and she finds herself trapped in a virtual world made of stuff straight out of her nightmares.

I’m also making a sci-fi feature film, ‘Her Broken Shadow’, with a similar theme, about an anthrophobic writer who begins to question reality when one of her characters materialises and forces her to relive the crimes she committed in her childhood. It should be ready by the end of this year. I don’t have a lot of film plans this year, apart from finishing ‘Her Broken Shadow’ (and maybe a web-series about a lone spaceman stranded in a spaceship, who comes upon a planet with only one woman in it, or what he thinks is a planet with only one woman in it), so I think I’ll have a lot of time to write a lot of short stories. I’ve already had two accepted for publication, one with Mithila Review, a new South Asian SFF mag, the other with Myriad Lands Anthology. My ultimate goal is to get into one of the top magazines, and maybe get myself into one of the big prizes, so fingers crossed.

I am learning a lot from each of these interviews with the authors and I really appreciate Dilman Dila sharing such deep insights into his novella - and the different ways in which the components of the story (Christianity and traditional religions, ancient beings, the folklore, conflict and more) led to its creation. Thank you again for taking the time to answer them. Join me tomorrow for the next novella in the series, VIII.