Mary Mitchell

Mary Mitchell, a doctoral candidate in the history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, recently completed her term as Resident Scholar in the OSU Libraries Special Collections & Archives Center. Mitchell is the first of the 2014-15 class of Resident Scholars to complete her work here in Corvallis.

Mitchell’s research subject was the Fallout Suits, a topic that has been examined by two previous resident scholars, Toshihiro Higuchi (2009) and Linda Richards (2011). However, where Higuchi examined this chapter of Pauling’s activism through the lense of environmental impact and Richards viewed the case as an instance of early human rights intervention, Mitchell, who has a background in law, is interested in the broader socio-legal milieu that surrounded the Paulings and their allies as they pursued their objectives.

The Fallout Suits can trace their origin to March 1st, 1954, when the United States tested the most powerful bomb ever to be exploded. The site for test Castle Bravo was Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands, then a U.S. territory. The blast came from a hydrogen bomb and was seen over 100 miles away. Radioactive debris from the test exploded high into the atmosphere and spread across the Pacific Ocean, carried by wind and water and causing damage to fisheries and ecosystems across the region.

“Castle Bravo,” the first hydrogen bomb test, March 1, 1954. (U. S. Dept. of Energy photograph)

The strength and destructive power of the blast far exceeded the expectations of the scientists who developed the bomb and quickly became an issue of international attention, mainly due to concerns over the spread of radioactive debris – fallout – which resulted from the test. Activists who saw radioactive fallout as a threat to the health and well-being of the public began to protest the continuation of these tests, leading at one point to a series of lawsuits filed against the governments of the United States, the Soviet Union and Great Britain.

This bundle of litigation, which sought to obtain judicial restraint to end nuclear weapons tests, quickly became known as the Fallout Suits. The American plaintiffs were Linus Pauling, Karl Paul Link, Leslie C. Dunn, Norman Thomas, Stephanie May and William Bross Lloyd Jr. This group was joined by several additional plaintiffs from Japan and Great Britain.

Mitchell’s research indicates that, during this chapter of the Cold War, Pauling was able to voice his opinions in a more successful way than was the case for lower-profile scientists of the time. While Pauling was indeed tracked by the FBI, the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee and other U.S. government entities hellbent on sussing out communist activities, Mitchell suggests that Pauling’s celebrity was both “his sword and shield” throughout the struggle. Pauling’s receipt of the Nobel Prize for chemistry and the fame that came with it protected him, at least to a degree, from being quieted as easily as was the case for other citizens at the time. Yet Pauling could not argue alone; in his fight against government policy he would need the support of other scientists to provide not only their opinion, but also their research, showing that nuclear testing is a threat to the public.

According to Mitchell, this strategy in Pauling’s fight against nuclear testing stemmed from his belief that democracy was only complete when citizens are given complete information in order to participate in the politics of their nation. As a scientist, Pauling knew that while nuclear testing could strengthen the military power of the United States, there were much broader consequences to this practice. He believed that the public should be informed about the dangers of nuclear testing and that the citizens of the United States should have a voice in determining whether or not these tests should continue. Pauling was especially firm in his belief that, as citizens, scientists should participate in public affairs by providing the public with information that would help individuals to make informed decisions when exercising their democratic rights.

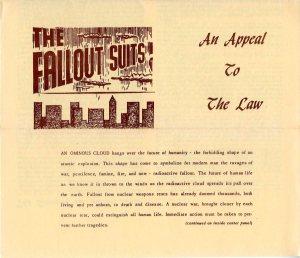

Fallout Suits brochure, 1958.

Though they gained the support of other scientists, the plaintiffs behind the Fallout Suits lost without even getting a trial; the courts took a stance on issues of justiciability (limitations on issues over which a court can exercise its authority) and standing (appropriateness of a party initiating a legal action) in dismissing the lawsuits. Additional Marshallese lawsuits were dismissed on the grounds that the plaintiffs were not U.S. nationals, even though the Marshall Islands were a territory of the United States.

Mitchell concluded her Resident Scholar talk by noting that, despite their ineffectiveness in compelling immediate government action to reduce nuclear testing, the Fallout Suits led to “new forms of participatory democracy, stretching trans-nationally across the Pacific Ocean,” forms of democracy which “had risen from the ashes of America’s testing program.” Moving forward, Mitchell will continue to dig into the research that she conducted at OSU as she develops her dissertation on legal challenges to atmospheric testing.

For more on the Resident Scholar Program, now in its seventh year, please see the program homepage and our continuing series of posts on this blog.