Marble is a metamorphic rock; i.e. what was originally sedimentary carbonate rock (most commonly limestone or dolomite) has been transformed by the action of temperatures in excess of 150 C and often considerable pressure into a different structure without it having melted. Typically those original carbonate mineral grains have crystallized (or re-crystallized) in the transformation into an interlocking mosaic thoroughly meriting the name ΟΏ�Οι�ος (marmaros ), ancient Greek for crystalline or shining rock. Sometimes its tone is uniformly pure. Often it is shot through with colouration from impurities, giving a striated, marbled (QED) effect.

There are many types and grades of marble. As chance would have it, the purest, fine-grained white marble came historically from Greece, Pentelic marble quarried on Mount Pentelicus in Attica, and Parian marble from the island of Paros, which we visited in 2019. Either or both would have been the source of the marble that was used in the construction of so many ancient Greek buildings with their ornate columns, friezes and statuary.

a marble forest

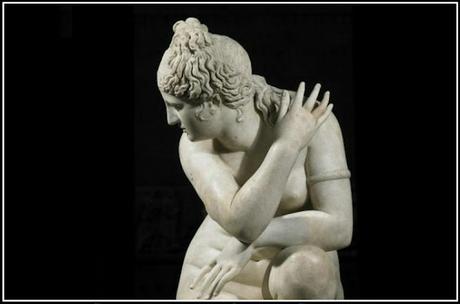

Of course there are other famous 'named' marbles. Carrara from Italy is probably most widely known. Then there is Makrana from Rajasthan in India. which was used to build the Taj Mahal, Nero Marquina from Spain, a black marble, Purbeck, the commonest English marble, and Prokonnesos, fittingly from Marmara Island in Turkiye, though there are dozens more. Turkiye is actually the world's biggest exporter of marble (with 42% of the global share) followed by Italy, Greece and Spain. Unsurprisingly, the modern demand for marble is not for colonnades or sculpture but for flooring, kitchen work surfaces and luxury bathrooms.What I did light upon when searching the marmoreal world with regal connections was this exquisite statue of Aphrodite (below) currently on display in the British Museum but actually on loan from the Royal Collection. It dates from the Antonine period (2nd century AD) and is a Roman copy of an earlier Greek original from approximately 200 BC, whereabouts now unknown. This Roman sculpture was brought to England during the first Carolean era by King Charles I, a renowned collector of Roman antiquities and beautiful women.

the Antonine Aphrodite

It was sold to the King by Duke Vincenzo II of Mantua and is listed in a Royal Collection inventory of 1631 as having been acquired from the Duke's Gonzago collection. When Charles I was executed, it was auctioned off in 1650 as part of the Commonwealth Inventory Sale. It went for £600 to the artist Peter Lely, but was returned to the Royal Collection in 1682, some twenty years after the restoration of the monarchy. At the beginning of the last century it was relocated from Kensington Palace to Windsor Castle, where it graced the Orangery for decades. It has been on long-term loan to the British Museum since 1963.Although marble is thought of as being durable, it is not nearly as tough as an igneous rock like granite. When exposed to an increasingly polluted atmosphere full of acids, the calcium carbonate in the rock reacts with the acids to produce salts and carbon dioxide, corroding the surface. (For the same reason, proud marble worktop owners, you should never clean them with vinegar.)

But marble is solid, you'll agree, and a marble floor is a durable thing of beauty. Which leads me on to recounting the strangest sight I ever beheld. It was while holidaying on the Greek island of Zakynthos some years ago. We were staying in a pleasantly appointed villa with marble floors. We had been advised that we were in earthquake territory and that there had been a series of tremors in preceding weeks, but nothing too serious. We were also told, if we felt one, that the safest thing to do was to stand in a doorway. (Not good advice, by the way. The safest place is under a table.)

dappled shade, Zakynthos villa

The tremor struck late one afternoon. First of all, everything went quiet, the cicadas ceased droning, the birds stopped twittering. Then there was a loud rumble like a jet plane and the shockwave hit. It was over in a matter of seconds. There was no structural damage, a few things rattled, but the spookiest part of all was to see that marble floor momentarily act like a wobbling jelly as the shockwave passed through. I know in theory that every solid thing is more space than substance, (I've even written poems on the topic), but unless I'd witnessed it with my own eyes that afternoon, I wouldn't have believed that something as rigid and substantial as marble could ripple like a jelly. It was astonishing.For KristelKnow that for all your immutable beautyyour cool hauteuryour marble heartthe way it crackedso easily susceptibleto the shivering wavein a chaos of depravityhas left us shockedthough yes of coursewe'll help pull youout of the rubbleafter the fact pretendnothing happenedyou back on that plinth.

Email ThisBlogThis!Share to TwitterShare to Facebook