Queen Victoria was in mourning for her beloved Prince Albert for forty years between his death in December 1861 and her own in January 1901, a period that comprised the majority of her reign. It’s no surprise therefore that when most people are compelled to think of Queen Victoria, it is the black clad little widow that springs immediately to mind, with her prim expression, Indian diamonds around her plump throat and, possibly, what appears to be a lace tablecloth fastened to her iron gray hair.

It’s sad really though – so pervasive is this popular imagining of Queen Victoria that most seem to forget that she was young once too, full of vibrancy, a love of dancing and, above, am all consuming passion for her handsome German husband. Faced with the grim faced Widow of Windsor, it’s also easy to forget that Victoria was only forty two when her husband passed away, which isn’t even middle aged by modern standards.

Victoria and Albert. Photo: Royal Collection.

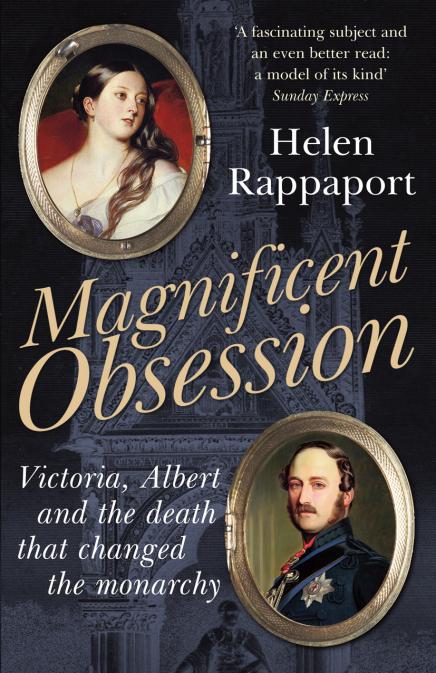

Despite the plethora of biographies of Victoria, it is perhaps surprising that Helen Rappaport’s superb Magnificent Obsession: Victoria, Albert and the Death That Changed the Monarchy is the first to explore in detail both the circumstances of Prince Albert’s death and the first decades of Victoria’s mourning, which encompassed great changes within her own family and within her realms as well as stirrings of serious social discontent as the beleaguered and rather self centred Queen isolated herself away from public view.

Magnificent Obsession opens with a glimpse of the royal family gathered together for a happy Christmas at Windsor Castle at the end of 1860 with all the traditional trappings of presents beneath the tree and a wonderful feast for all their household. What could be more perfectly homely after all than a Victorian Christmas? However, there were serious tensions at play beneath the cosy if rather opulent exterior – Victoria, always neurotic and prone to hysterical outbursts of rage, was highly strung and difficult as always, much to the despair of her externally devoted husband, who was privately becoming worn out and fed up with dealing with her, as well as progressively more bored with her excessive devotion to him.

The presence of the couple’s children, whilst it made the ancient castle resound with noise and fuss, did little to soothe their parents’ ruffled tempers as the relations between Victoria and her offspring, and in particular her eldest son Bertie, Prince of Wales, was generally a rather strained one at best and at worst, absolutely wretched. I’m not sure that Victoria disliked her children quite as much as a recent BBC documentary series about her children would have us believe but it’s well documented that she found babies very tiresome and disliked any clashes of wills with her older children quite excessively, which was unfortunate as she seemed to be in the habit of producing offspring as pig headed and wilful as herself.

Victoria and Princess Alice in mourning. Photo: Royal Collection.

At the time of Prince Albert’s untimely death, the royal family were embroiled in a rather tawdry scandal involving their eldest son and a good time girl attached to the barracks where he had been residing in Ireland. Whereas an aristocratic couple would have shrugged this off as the natural peccadillos of a well heeled young gentleman, Victoria and Albert were completely horrified, with the latter being particularly distressed by it all and fearing that his son was a throwback to the disreputable shenanigans of Victoria’s dreadful pack of uncles not to mention his own father. In this respect he need not have worried as the late unlamented Duke of Saxe Coburg-Gotha had treated women terribly, whereas Bertie was cut from an altogether different and much more amiable cloth.

Rappaport goes into a great deal of detail about Prince Albert’s last days, which were mostly spent reclining on a day bed in his rooms at Windsor Castle, surrounded by his adoring family. Up to the very last, the royal doctors tried to hide the seriousness of his illness from Victoria, fearing as everyone did a descent into histrionics as she grappled with the potential loss of her soulmate. Victoria’s mother had died earlier in the same year and she had seemingly given herself over to an orgy of hypocritical and excessive grief – hypocritical because she had never seemed all that fond of her mother when she was actually alive. Everyone feared even more excesses should she lose Prince Albert.

Prince Albert himself hadn’t been altogether approving of his wife’s lavish mourning after the death of his mother in law (to whom he himself had actually been rather close) and it seems probable that he would have been aghast had he known how Victoria would react to his own demise. He certainly stipulated that he didn’t want any showy monuments to himself popping up all over the place – a request that his wife cheerfully ignored in her keenness to ensure that everyone knew how important her late husband had been to her and assumption that they all shared her veneration.

Mourning ring worn by Queen Victoria. Photo: The Royal Collection.

Victoria’s mourning was stark and absolute as she immediately retreated with her children to Osborne House to spend a very gloomy Christmas. At first everyone was highly sympathetic – very few, it would seem, had any illusions about the fact that it was in fact Prince Albert who had dealt with the bulk of the state affairs that came the couple’s way, a responsibility that he had cheerfully taken on during Victoria’s numerous pregnancies and layings in. For her part, Victoria, despite that strong will and autocratic manner, had been only too happy to let her husband have his way with the result that his departure left her completely floundering and uncertain of how to act.

It’s significant really that one of Prince Albert’s last official actions was to intervene in a diplomatic crisis between Britain and America that threatened to plunge both countries into war and it was drily noted by at least one person that out of the two, Victoria’s death would have been less of a disastrous loss than his.

Poor Victoria though – difficult, bossy and completely self centred though she was, it’s hard not to be touched by the profundity of her grief and the terrible loneliness that she must have felt. Rappaport describes how the every day rituals of Prince Albert’s rooms, of water being poured and clothes being laid out, carried on regardless as though he were still alive and how photographs of his dead body, recumbent on his daybed just hours after death, were hung above his side of the bed in Victoria’s bedroom, while she herself slept fitfully every night with his dressing gown beside her and one of his coats over her blankets. There’s also mention of the fact that guests at the royal residences were still required to write their names in Albert’s visitor’s book as well as Victoria’s, almost as if they were paying a call on a man now dead, which must have been rather unnerving.

Victoria with her faithful John Brown. Photo: The Royal Collection.

Public sympathy for the widowed Queen soon began to wane though and the majority of the book follows the first few decades of Victoria’s mourning as she first sequestered herself away from public view, surrounded by her exhausted, unhappy and rather bullied daughters and then, encouraged by John Brown and the likes of Disraeli, gradually began to come out of her shell and make occasional appearances. It was a bleak time though and without the visible presence of a monarchy, disaster very nearly struck as radical newspapers questioned why the Queen received so much money from the public purse if she didn’t seem to do anything with it? She had given up entertaining foreign dignitaries for a start, which was considered highly rude and inadvisable.

The book ends as the tide begins to turn for Victoria, first with the publication of her book Leaves from the Journal of our Life in the Highlands, which was a massive bestseller and then with the near death and recovery from Typhoid Fever of her eldest son, the Prince of Wales, a figure of immense popularity. It then goes on to look at the death of Victoria’s second daughter, Princess Alice who had been her main prop and support after the death of Albert and then, finally, a look at the probable causes for his passing away. It’s always been traditionally assumed that Typhoid was the culprit but Rappaport looks at several possibilities and considers his pre-existing health issues before concluding that Crohn’s Disease may well have been the cause, exacerbated by the stress caused by poor Bertie’s little affair in Ireland so Victoria’s baleful accusations that he was to blame for his father’s death may not have been so wide of the mark after all.

As you might expect, this isn’t the most cheerful book in the world with all its description of Victoria’s mourning and the related expansion of the Victorian funeral industry, but I was honestly gripped. I’d recommend this one to anyone interested in Victoria and Albert or with a thing for the more morbid side of history.