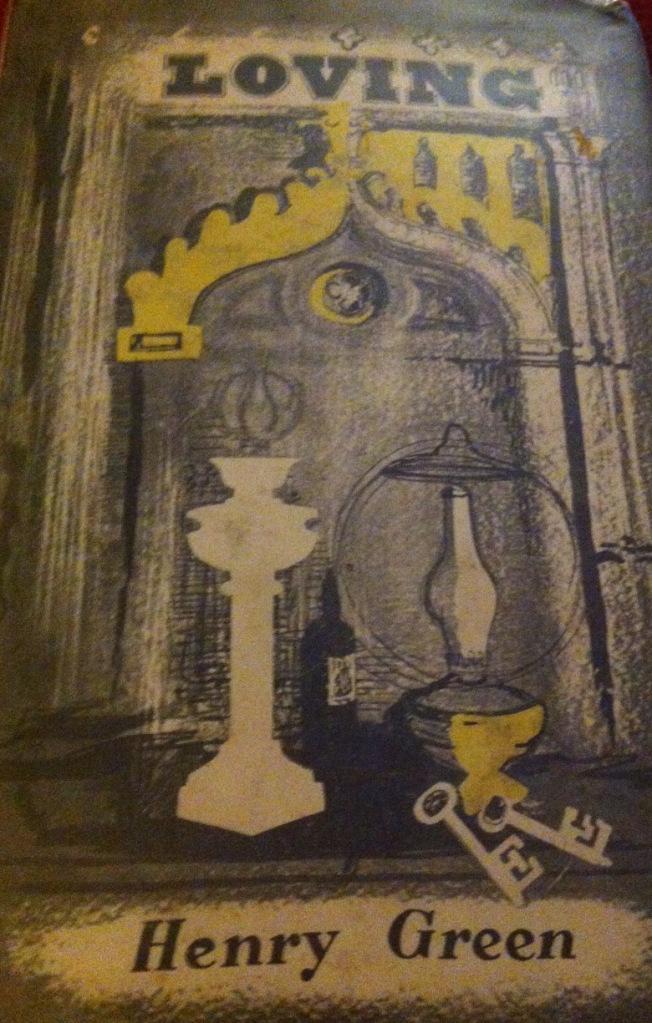

A spate of bloggers read Henry Green earlier this year and raved about him, piquing my interest. I’d never heard of him before; subsequent research revealed that he was a prominent modernist writer, with a unique style that was highly praised by the likes of Elizabeth Bowen and W H Auden, and he was published by Virginia and Leonard Woolf at The Hogarth Press. With all these connections and accolades, I was rather surprised that I hadn’t come across him in my reading life before. Enthusiastic to try something of his, I popped a cheap used copy of Loving in my Amazon shopping basket, but for some reason didn’t buy it. I then completely forgot all about it. That is, until I ordered some books for school a couple of weeks ago, and an unexpected extra parcel arrived. Confused, I ripped it open to find a beautiful 1940s hardcover of Loving, complete with original John Piper dustjacket. I was pleased to have it, but didn’t plan on reading it right away; I was in the middle of something else and was going to relegate it to my very long TBR pile. However, before I went to bed that night, something made me want to start reading. I opened it up, just planning on scanning the first page. An hour later, I was still turning the pages voraciously, not wanting to stop. To my very pleasant surprise, I found it absolutely mesmerising, despite it being just the sort of book I don’t normally like. Intriguing, no?

Set in the Irish country house of widowed Englishwoman Mrs Tennant during the early days of WWII, Loving mainly concerns the personal lives of the household staff. As the novel opens the old butler dies and the mantle is passed onto Charley Raunce, who has been eyeing up the top job for years. This causes great consternation in the house, with Miss Burch, the highly sensitive housekeeper, taking umbrage at the uncouth and disrespectful Charley taking over from the adored Mr Eldon. Miss Burch rules over the two young and giggly housemaids, Edith and Kate, while the gin drinking cook Mrs Welch rules over her kitchen girls, who are never allowed to fraternise with the tradesmen who come calling. For this is a household of English staff marooned in a foreign and hostile land; Ireland is a savage place according to the staff at the Castle, and they live in fear of being besieged at the back door by the IRA. However, with the war raging just across the Irish Sea and the certainty of being called up to war work or the army if they set foot back on their native land, they have no option but to stay put and live in a state of constant agitation. On the plus side, they have a very good deal; in the wilds of Ireland during a war, domestics can’t be found for love nor money, and Mrs Tennant and her daughter in law Violet find themselves held to ransom by the demands of their often difficult household staff.

The passing of Mr Eldon triggers a period of upheaval in the house. When Mrs Tennant and Violet go over to England for an extended visit, the staff are left alone to fend for themselves. Mrs Swift, the old Nanny, retires to her bed, as does Agatha, unable to cope with the stress. Charley, young Albert the footman and the girls are left with a free rein of the house, and Charley and Edith’s long burgeoning love affair is allowed to flourish. These are long days of largely nothingness; Edith looks after Violet’s abandoned children, Miss Moira and Miss Evelyn, in the peacock filled gardens; Charley watches Kate and Edith dancing in the shrouded drawing room; there is drama over an accidentally murdered peacock and a missing ring. This is not a plot driven novel; it is a study of character, written with an astonishing attention to detail and a lyricism that is astoundingly beautiful. There are moments in Green’s prose where you just have to stop, re-read, re-read again and then sit back and allow the images he creates to distil and unfold, chrysalis-like, in your mind. In a few words, he creates an entire world in meticulous minutiae; one that bursts with colour and seethes with repressed emotion, all encased in a veneer of fear of the unknown wilds of the countryside that unfolds outside of the closeted grounds.

The novel is mainly written in dialogue; ordinarily I can’t stand this, but in Loving, it feels entirely natural. Each character bursts effortlessly to life, their dialogue infused completely with their individual personalities. I felt like I was reading a play, and one that was being staged in a slightly fantastical location at that. The Castle is an intriguing background; a gothic pile with rooms heaped with ornate and unusual objects, it appears totally incongruous with the brash simplicity of the majority of people who inhabit it. Even the vague Mrs Tennant never feels quite at home there; it is a strange and uncomfortable place that everyone seems desperate to get away from. It is a fairytale castle, a symbol of the once almighty aristocracy whose power has been rapidly eroded, and its otherworldly quality perhaps stems from the fact that it is largely empty, and actually lived in more by the servants than the aristocrats. The social order has become inverted; the domestics rule the roost here, reflecting the turmoil in the world outside which the inhabitants of the Castle are hiding from.

This is a magical, special, uniquely brilliant novel, that merits endless re-reading and analysis to fully appreciate the splendour of the language Green uses to weave his tale. I loved how the opening and ending lines created a frame of a traditional fairytale, undermining the reality of the novel and reminding us that we are in a pretend world, where everyone is escaping from the realities of life. It is not just an aesthetically pleasing work of literature, however; it is also a hugely entertaining and very funny exploration of character. I adored every minute of reading it; even if you think modernism isn’t for you, you have to give Henry Green a try. I can’t wait to read more. This is literature as its best; an absolute feast for the imagination.

He drew and drew again cautious as if he might be after a deep draught of her, of her skin, of herself. He was puffed already when his arms went out to go round and round and round her. But she was not there and for answer he had a storm of giggles which he could not tell one from the other and which went ricochetting from stone cold bosoms to damp streaming marble bellies, to and from huge oyster niches in the walls in which boys fought giant boas or idled with a flute, and which volleyed under green skylights empty in the ceiling.