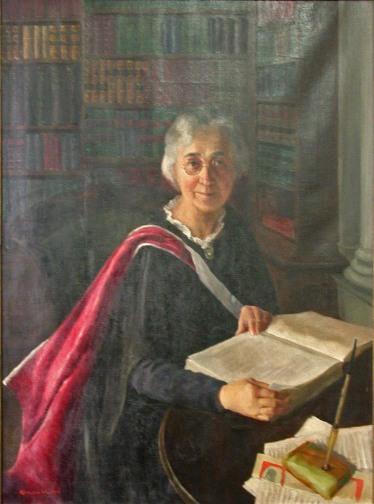

Lilian Lindsay, by Kathleen Williams

Lilian Lindsay, by Kathleen WilliamsI have been taking photos of English Heritage’s blue plaques featuring women for quite some time now, meaning to research their lives and form a directory of some nature. So today’s post will be the first of many monthly posts, doing just this. I hope you’ll enjoy finding out more about these many remarkable women!

First up, is Lilian Lindsay (1871-1960), who was the first female dentist to qualify in Britain; note the Britain and not England, as she was forced to move from her home in London to study dentistry in Scotland, as no school in England would accept her. According to the British Dental Association’s very informative profile of her here, she was interviewed for a place at the National Dental Hospital in London on the pavement outside, as the hospital’s director, Henry Weiss, was so concerned that her very presence in the building would form a distraction to male students that he wouldn’t let her in the building. Rejected from her applications to study in England, she went north to Edinburgh, where she was accepted to the city’s dental school, though not without being told by a member of staff there that in doing so, she was taking the bread from a male student’s mouth.

Lilian well and truly proved her detractors wrong through her remarkable capacities as a surgeon and scholar. She won the Wilson Medal for dental surgery and pathology and the medal for materia medica and therapeutics in 1894, and qualified in 1895, becoming the first woman in the UK to do so. She promptly moved back to London, where she established a highly successful dental surgery in Hornsey, North London, and worked for ten years to pay off the bank loan she had taken out to fund her studies.

The bank loan paid off, Lilian married her former university tutor, Robert Lindsay, in 1905. They practised as dentists together in Edinburgh, and were prominent members of the newly established British Dental Association, with Lilian being its first female member. Passionate about her profession, and particularly its history, Lilian became the honorary librarian of the BDA in 1920 when her husband became its secretary. The couple moved into a flat above the BDA’s offices in London’s Russell Square, where Lilian remained after her husband’s death ten years later, and all throughout the Blitz, refusing to leave the library’s precious resources unguarded. Lilian founded the BDA’s library, amassed a world-leading collection on the history of dentistry, and learnt numerous European languages, as well as Old English, to help with her research and translation of historical artefacts. She published a book, A Short History of Dentistry, in 1933, and contributed tens of journal articles to the British Dental Journal, for which she was sub editor for twenty years. She became the first female president of the BDA in 1946.

A leading figure in both the practice and history of dentistry, Lilian was a true pioneer whose perseverance in the face of much resistance to women’s involvement in the world of medicine enabled her to make an enormously valuable and long-lasting contribution to her chosen field. Despite attending Frances Mary Buss’ pioneering North London Collegiate School for Girls as a teenager, Lilian was advised by her teachers to give up any idea of studying dentistry and instead become a teacher – a far more fitting career for a woman. Strong-minded enough to ignore this discouragement, Lilian managed to gain a three year apprenticeship to experience dentistry for herself, and after scraping together enough loans to do so, applied to study dentistry, refusing to give up when she could find no school in England willing to take her. She didn’t allow societal standards, rejection or financial difficulties to stop her from striving to achieve her dreams, and in daring to believe that she could do what no other woman had done before, she made history and paved the way to making dentistry a profession where, in the UK, women are now the majority.

A blue plaque was placed on Lilian’s childhood home in North London in 2013; sadly, a developer illegally demolished the house, and so her plaque was moved to the house where she lived in Russell Square last year. Bloomsbury, where Russell Square is situated, is a treasure trove for blue plaques commemorating women, and I’ll feature another remarkable resident next month.