I felt slightly uncomfortable about the premise (given it concerns the sexual precociousness of teenage girls) but Vladimir Nabokov, who wrote the novel in the mid '50s, remains one of my favorite authors - and one of the true literary masters - so I re-watched the original movie adaptation of the novel (having read the book at university some 40 years ago) and began working on a poem. I'm not sure the arts project ever materialised; the trail went cold.

There it would have ended apart from two things: the fact that I don't like leaving works unfinished and the resurfacing media attention given to the unacceptable practice of 'grooming' young girls in English towns.

Of his most famous novel, Nabokov had this to say: "Lolita is a special favorite of mine. It was my most difficult book - the book that treated of a theme that was so distant, so remote, from my own emotional life that it gave me a special pleasure to use my combinational talent to make it real. Of course she completely eclipsed my other works... but I cannot grudge her this. There is a queer, tender charm about that mythical nymphet."

Born in Russia, from whence his family fled in advance of the 1917 Bolshevik revolution, Vladimir Nabokov grew up in exile in western Europe, studied modern languages at Trinity College, Cambridge and then became a novelist, writing first in Russian and then, following his move to the USA during the 2nd world war, in English. When he was writing Lolita, Nabokov was so concerned about how the book might be received that he even considered publishing it under a pseudonym, the appropriately anagrammatical Vivian Darkbloom.

When the novel appeared it was considered controversial, shocking even in its subject matter and acquired a reputation for being a risque book (especially by those who had not read it) but Lolita has gradually cemented its place among the finest works of fiction of the 20th century.

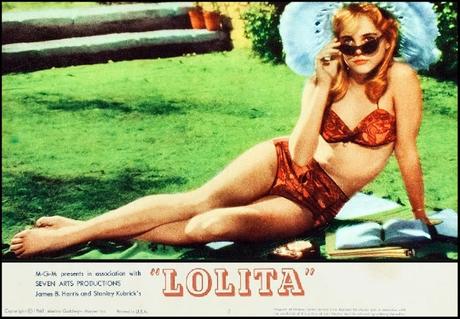

I am not going to summarise the plot here, beyond saying that it concerns a middle-aged professor's unhealthy infatuation with Dolores Haze, the teenage daughter of his landlady. I recommend you to read the novel. Lolita, pictured below from Stanley Kubrick's 1962 film, was the pet name that Humbert gave to Dolores. The story of Lolita has been filmed twice, by Kubrick as mentioned and more recently by Adrian Lyne in 1997. It has also been adapted as a stage play and a ballet and is the subject of two operas.

Still from Stanley Kubrick's original 1962 movie of the novel

The protagonist of the novel claims he has hebephilia. I had to look it up. It's a fixation with pubescent girls (named after the Greek goddess Hebe, protector of youth if you wanted to know) and has been brought on in his case by an unfortunate event in his own younger life - so a form of mental illness (interestingly first 'diagnosed' by clinicians as Nabokov was planning the book). As such it is only one rung above paedophilia on the ladder of unacceptable sexual fixations. His predilection gets him into all sorts of trouble and yet such is Nabokov's talent as an author that there is sympathy even for the tormented professor.Dolores Haze may or may not have been sexually precocious. Humbert may have been as much victim as predator, with genuine feeling for Lolita. You would need to read the novel and arrive at your own conclusion. The 1950s seems such an innocent decade in retrospect. It is telling, I think that the Lolita of Lyne's 1997 movie was altogether more seductive and sophisticated than her earlier namesake.

Lolita remade, remodelled - innocence lost

It is perhaps understandable that young teenage girls want to look and act mature beyond their years, that they have a natural need to explore and understand their power to attract. A few may even exploit that power without appreciating the possible consequences. However, one thing is indisputable, I believe - that is the absolute moral responsibility of the adult not to take advantage of the child, no matter the extent of the opportunity or the provocation. If the Liverpool art project had come to fruition, it may have put that moral consideration into the public domain.Here, at least, is the poem I wrote concerning Lolita. I don't quite know what I was trying to do with it (apart from somehow capturing the ambiguity inherent in the psyche of a hebephiliac) and I feel quite ambivalent about it - so your candid feedback is welcomed.

Nymphet

Nymphet, floret,

languid miss Dolores Haze,

pallid, unsullied temptress -

the mere thought

of your slender splendour

orchestrates a symphony in my head;

and though I dance to your tune,

my tight-budded flawless empress,

this manly madness is no mere lust.

My tender yearning

for your pure, demure young love

is such

that I could not betray your trust,

would never stoop to groom

or bruise the fruit of your bloom

even though your coyness flays me.

Thanks as ever for reading. Be good, S ;-) Email ThisBlogThis!Share to TwitterShare to Facebook

Reactions: