The Brazilian Bach

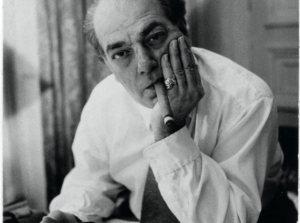

Heitor Villa-Lobos (classicfm.com)

The standard contract for many visiting vocal artists allowed them to appear in a work of their own choosing — for instance, one of the rollicking stage comedies of Italian composer Gioacchino Rossini — while it stipulated for others that they perform in at least one national opera, usually those of the late Carlos Gomes.

But other important Brazilian works were represented as well, beginning with the operas of the aforementioned Henrique Gurjão (Idália, 1881) and Leopoldo Miguez (Pelo Amor! 1897; Os Saldunes, 1901), followed by the earnest efforts of Henrique Oswald (La Croce d’Oro, 1872; Il Neo, 1900; Le Fate, 1902), João Gomes de Araújo (Edméa, 1886; Carmosina, 1888), Francisco de Assis Pacheco (Moema, 1891; Flora, 1898; Estela, 1900), Alberto Nepomuceno (Electra, 1894; Artemis, 1898; Abul, 1905), Antonio Francisco Braga (Jupyra, 1898-99), Francisco Mignone (O Contrator de Diamantes, 1921; L’Innocente, 1927; Mizu, 1937; O Chalaça, 1973; O Sargento de Milícias, 1978), Mozart Camargo Guarnieri (Pedro Malazarte, 1932; Um Homem Só, 1960), and numerous others.

Yet the most distinguished of the Brazilian classical composers was not even present in this hardly illustrious pack. As if to take up the compositional power vacuum left by the untimely death of maestro Gomes, the young and hearty Heitor Villa-Lobos suddenly exploded onto the scene as a self-taught — and self-made — musical force onto himself.

With his endless fascination for popular and folk forms, and his incorporation of modern and neoclassical elements into his entire musical framework, Villa-Lobos appeared to possess the finest qualities of Dom Pedro, Carlos Gomes, and Arturo Toscanini, all rolled into one indomitable and charismatic entity: the eclecticism and intellectual curiosity of the emperor, blended with the ambition and musical talent of the composer, balanced against the poise and self-confidence shown by the conductor.

Here, at long last, the potential savior of the Brazilian national opera had conclusively emerged — or so it was believed — and began to loom large over Brazil’s expansive musical horizon almost from the very moment of his conception. What most readers and critics might find surprising about him — and what historically has been so glossed over, in view of the increasing number of revisionist accounts being offered by present-day researchers — is the prominent part Villa-Lobos played in crafting an absolutely unassailable mythology for himself. Unassailable, that is, until now.

The young Villa-Lobos circa 1922 (en.wikipedia.org)

Born in Rio de Janeiro, on March 5, 1887, as a premature infant (he could hardly wait to get started, it would seem), in the last decade before the end of the nineteenth century — and less than a year after Toscanini’s impressive debut in the same city — Heitor Villa-Lobos became, in the minds of most Brazilians, that peripatetic and immensely prolific musician of near Mozartean proportions he initially set out to be; one whose best work was consciously patterned after that of the German master Johann Sebastian Bach, whom he greatly admired.

The connection to Bach, one of Western civilization’s most industrious individuals, was indeed a prescient one in Villa-Lobos’ case: although he composed reams of widely performed church and organ pieces, Bach never wrote for the lyric stage (a serious man of faith, the inexhaustibly inventive genius may well have considered opera too frivolous a subject for his strictly Lutheran sensibilities).

Too, Villa-Lobos produced all manner of classical compositions, and, much like his European “mentor,” wrote in a wide variety of styles and genres. Yet most musicologists would be hard-pressed to name even one operatically themed work, a revealing fact of musical life that remains a mystery to this day.

Nevertheless, like the temperamental Toscanini before him, Villa-Lobos began in modest surroundings as a cello player, which, along with the clarinet, he learned to play at the tender age of six, thanks to a stern and foresighted parent named Raul:

“My father, besides being a man of first-rate culture and exceptional intelligence, was a practical, technically proficient musician. In his company I attended rehearsals, concerts, and operas, the purposes of which [were] to ground me in the nature of instrumental ensembles… he required me to discern the nature, style, and origin of the works, to quickly tell him the exact pitch of sounds or noise that I heard at any given moment, such as, for example, the screech of a streetcar on iron tracks, the chirp of a bird, or that of a falling metal object. All these things were done with discipline and absolute energy; poor me if I gave the wrong answer!”

Villa-Lobos would create some of his finest scores almost exclusively for that soulful string instrument, the cello (Grand Concerto, 1913; Fantasia for Cello and Orchestra, 1945), as well as for the guitar (Twelve Studies, 1923-25; Five Preludes, 1940), which he also mastered, and the piano (A Prole do Bebê, 1920-22; Cirandinhas and Cirandas, 1926). Indeed, it was a forgone conclusion that little “Tuhu” — “a runty, incorrigible child, undisciplined, willful and not at all coachable” — was the only one of his seven siblings destined to do something quite out of the ordinary in order to stand out from the crowd.

Blessed with an astonishingly accurate and refined ear for melodies, harmonies, chords, and colors of every shape and form, the incurably precocious boy from the bairro (“neighborhood”) of Laranjeiras soon started congregating with local street musicians, nightclub singers, sidewalk artists, and other disreputable types; all the while picking up and playing their tunes and dance rhythms, and improvising to a new and unique style of music called choro, an early precursor to samba, which formed the creative backbone for many of Villa-Lobos’ body of instrumental works:

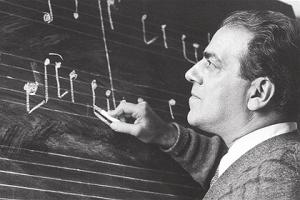

Villa-Lobos at work (tumblr.com)

“What is a Chôro [sic]? The Chôro is popular music. The Chôro of Brazil, as you could perhaps say about the samba or something else, but truly the Chôro, is always of the musicians that play it, of good and bad musicians who play for their pleasure, often through the night, always improvising, where the musician exhibits his talent, his technique.”

Here, There and Everywhere

The family moved several times while Villa-Lobos was still small — it might have had something to do with father Raul’s shady political past — but, for better or worse, the close-knit clan always managed to revert back to Rio. Regardless of where they resided, his parents strongly disapproved of their son’s association with these unsavory street sorts, the gist of which led to his being placed in a more “structured” musical environment.

After the premature passing of his father in 1899, Villa-Lobos could no longer be constrained from seeking an independent career in music, or from curbing his insatiable wanderlust. He abandoned plans to enter medical school and become a physician, a profession his mother, Dona Noêmia, once hoped he would take up, in favor of travel to every part of his adored Brazil.

Although documentary evidence of these excursions remains scant and unclear to this date, it is believed that between the years 1905 and 1907, and throughout 1907 to 1912, Villa-Lobos claimed to have paid frequent visits to the states of Espírito Santo, Bahia, and Pernambuco, in the Northeast, with occasional side trips to the South; to the central region of Minas Gerais, Goiás, and Mato Grosso; and to the Southeastern state of São Paulo. He purportedly explored parts of the Amazon rain forest, or so we are informed — a foray that, by all reports, left an indelible mark on the young wayfarer.*

In addition to the uniqueness of his individual style, “creativity” became an enduring part of Villa-Lobos’ historical legacy as well. Where does one begin? Why, every known and not-so well-known aspect of the composer’s life and art were suffused with this trait, which sometimes bordered on the pathological. Even at this seminal stage in his development, he was wont to display his storytelling skills at random, sometimes stretching his already incredible adventures to absurdly preposterous lengths. Tales of his having been captured by “native savages” or nearly devoured by “hungry crocodiles” were as fanciful and hard to fathom as those involving his alleged shipwreck off the coast of Barbados in the Caribbean — with his ever-present cello in tow, of course.

Constantly on the move during this period, which made it well-nigh impossible for him to be to pinned down about his various exploits, Villa-Lobos paused just long enough (in 1913) for a little romance and marriage to Lucília Guimarães, a respected pianist and composer, as well as a choral director, teacher, and arranger of note. She is said to have exerted a strong influence on her husband’s musical formation, which included lending a creative hand or two to many of his early compositions, and to his later piano-playing technique.

(End of Part One)

Copyright © 2012 by Josmar F. Lopes

* Early hagiographers took up this frequently cited point as if it were the unvarnished truth. Further research into what there is of the facts, however, revealed that Villa-Lobos’ brother-in-law, one Romeu Bormann, may actually have been the individual who partook of these so-called “extensive excursions” to Brazil’s interior (quite possibly with famed explorer Marechal Cândido Rondon), circa 1909-11. Villa-Lobos could very well have appropriated these stories about his relative’s jungle adventures for his own self-aggrandizing purposes.