The Pauling family anticipating Linus Pauling’s Nobel lecture, December 11, 1963. (Photo credit: Aftenposten)

On December 10th, 1963, Linus Pauling accepted the belated Nobel Peace Prize for 1962. Attended by the Norwegian royal family and various government representatives, the ceremonies took place in Festival Hall at the University of Oslo in Norway – separate, as per tradition, from the other Nobel Prize ceremonies in Stockholm, Sweden. Pauling shared the ceremonies with the winners of the 1963 Nobel Peace Prize – an award split between the International Committee of the Red Cross and the League of Red Cross Societies in commemoration of the centennial of the founding of the Red Cross.

Gunnar Jahn, the chair of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, introduced Pauling before presenting him with the prize. In his remarks, Jahn reconstructed the advances and setbacks of the post-war peace movement in which Pauling had so prominently operated since the dropping of atomic bombs by the United States on Japan. Escalating Cold War tensions and the arms race soon rendered as unlikely any hopes for an immediate era of peace. The nascent post-war peace movement, according to Jahn, “lost impetus and faded away. But Linus Pauling marched on: for him retreat was impossible.”

While Pauling”s peace work was surely political in nature, Jahn drew attention to the importance of Pauling’s scientific attitude in researching and determining the effects that atmospheric radiation may have on future generations. Even critics of Pauling, including the physicist and nuclear weapons engineer Edward Teller, did not fundamentally disagree with him concerning the harmfulness of fallout from nuclear tests. Where Teller and Pauling did conflict centered more on questions as to whether or not these harmful effects outweighed the advantages that they provided to the United States with respect to the Soviets. Pauling thought they did; Teller disagreed.

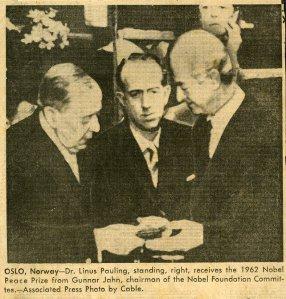

Pauling and Gunnar Jahn, ca. 1963.

Jahn then recounted how the public started paying close attention to Pauling in 1958 as he presented to United Nations Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld a petition signed by 11,021 scientists from fifty different countries calling for the end of above-ground nuclear weapons testing. Because of the petition, Pauling was called before Congress and questioned about alleged communist ties which, not for the first time, he denied. By Jahn’s estimation, the hearing only served to make Pauling a more popular and sympathetic character and he continued to speak out more and more.

For Jahn, Pauling’s 1961 visit to Moscow, during which he delivered a lecture on disarmament to the Soviet Academy of Science, illustrated Pauling’s importance in propelling the Partial Test Ban Treaty, which came into effect two years later. While there, Pauling unsuccessfully sought to meet with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev. Unbowed, he instead sent Khrushchev two letters and a draft nuclear test ban agreement. “In the main,” Jahn emphasized, Pauling’s

proposal tallies with the test-ban agreement of July 23, 1963. Yet no one would suggest that the nuclear-test ban in itself is the work of Linus Pauling… But, does anyone believe that this treaty would have been reached now, if there had been no responsible scientist who, tirelessly, unflinchingly, year in year out, had impressed on the authorities and on the general public the real menace of nuclear tests?

Ultimately, for Jahn, it was as a scientist that Pauling helped move the world toward peace. Looking forward, Pauling’s proposed World Council for Peace Research would bring together bright minds from the sciences and humanities under the auspices of the United Nations in hopes of seeking out new institutional models and paths of diplomacy for a nuclear-armed world. Jahn closed by suggesting that “through his campaign Linus Pauling manifests the ethical responsibility which science – in his opinion – bears for the fate of mankind, today and in the future.”

Associated Press photo published in the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, December 10, 1963.

After concluding, Jahn called Pauling to the stage; applause and a standing ovation from the crowd quickly followed. After the applause had died down and Jahn presented Pauling with the gold Nobel medal and a certificate, Pauling delivered a brief acceptance speech, calling the prize “the greatest honor that any person can be given.” But Pauling also recognized that his prize was likewise a testament to “the work of many other people who have striven to bring hope for permanent peace to a world that now contains nuclear weapons that might destroy our civilization.”

Pauling went on to draw similarities between himself, the first scientist to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, and Alfred Nobel, who endowed the Nobel Foundation. Both were chemical engineers interested in scientific nomenclature and atomic structure. Both owned patents on explosive devises – Nobel the inventor of dynamite and Pauling an expert on rocket propellants and explosive powders whose skills came to bear during World War II. And both expanded their interests into biology and medicine as well. Many had described Nobel as a pessimist, but Pauling wished to assure his audience that this was not the case and that, like himself, Nobel was an optimist who saw it as “worthwhile to encourage work for fraternity among nations”

Pauling, holding the case containing his Nobel certificate, being congratulated by Norwegian King Olav V. Image originally published in Morgenbladet, December 11, 1963.

The following day, December 11th, Pauling gave his Nobel Lecture, “Science and Peace.” In it he described how the advent of nuclear bombs was “forcing us to move into a new period in the history of the world, a period of peace and reason.” Development of nuclear weapons showed how science and peace were closely related. Not only were scientists involved in the creation of nuclear weapons, they had also been a leading group in the peace movement, bringing public awareness to the dangers of such weapons.

Pauling recounted how Leo Szilard – whose 1939 letter to President Roosevelt (and co-signed by Albert Einstein) had led to the Manhattan Project – urged Roosevelt in 1945 to control nuclear weapons through an international system, a plea that was issued before the first bombs had been dropped. While Szilard’s appeal fell flat, it was followed, in 1946, by the creation of the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, a group overseen by Szilard, Einstein and seven others, including Pauling. Over the next five years, the committee warned of the potentially catastrophic consequences of nuclear war and advocated for the only defense possible: “law and order” along with a “future thinking that must prevent wars.”

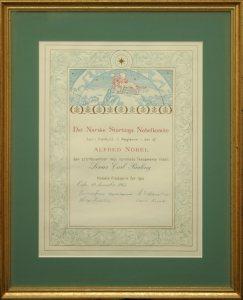

Pauling’s Nobel certificate, 1963.

Other groups followed. For Pauling, the Pugwash Conferences, headed by Bertrand Russell from 1957 to 1963, were particularly influential in bringing attention to the harmful effects of nuclear testing and, ultimately, the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty. It was during this time that nuclear fallout, the subject of Pauling’s 1958 petition, became of greater concern. The importance of fallout centered on the potential genetic mutations to which several generations would be exposed. Pauling quoted the recently assassinated President John F. Kennedy to support his point: “The loss of even one human life, or malformation of even one baby – who may be born long after we are gone – should be of concern to us all.”

As matters stood in 1963, Pauling warned that the time to effectively control nuclear weapons was fast slipping away. The test-ban treaty was, Pauling lamented, already two years too late and had not prevented the large volume of testing that took place after the Soviets – who were quickly followed by the United States – had broken the 1959 testing moratorium in 1961. The failure to end testing outright before 1960 led to the explosion of 450 of the 600 megatons detonated during all nuclear tests.

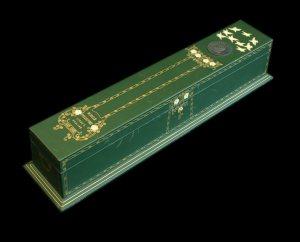

Pauling’s Nobel certificate case, 1963.

Because of the sheer number of nuclear weapons in existence (Pauling estimated some 320,000 megatons) limited war was not a feasible plan due to “the likelihood that a little war would grow into a world catastrophe,” both immediate and long-term. Abolishing all war was the only way out. But standing in the path of the abolition of war were people in powerful positions who did not recognize the present dangers and the need to end war. Pauling also saw China’s exclusion from the United Nations, which prevented the nation from taking part in any discussions on disarmament, as an additional roadblock to a lasting world peace.

To get around these blockades, Pauling proposed joint national and international control of nuclear weapons as well as an inspection treaty aiming to prevent the development of biological and chemical weapons, which could become a threat of equal measure to nuclear weapons. Additionally, Pauling felt that small-scale wars should be abolished and international laws established to prevent larger nations from dominating smaller ones.

The challenges of the era were great but Pauling ended optimistically:

We, you and I, are privileged to be alive during this extraordinary age, this unique epoch in the history of the world, the epoch of demarcation between the past millennia of war and suffering and the future, the great future of peace, justice, morality and human well-being… I am confident that we shall succeed in this great task; that the world community will thereby be freed not only from the suffering caused by war but also, through the better use of the earth’s resources, of the discoveries of scientists, and of the efforts of mankind, from hunger, disease, illiteracy, and fear; and that we shall in the course of time be enabled to build a world characterized by economic, political, and social justice for all human beings, and a culture worthy of man’s intelligence.

The Nobel medal, obverse.

The response to Pauling’s speech by the American press was fairly tame. Most headlines simply issued variations on “Pauling Gets His Prize.” A handful of headlines delved into the substance of Pauling’s lecture, one noting “Pauling Accepts Award, Sees World without War in Sight.” Others emphasized the means by which he sought to end war, e.g. “Pauling Urges UN Veto Power on Nuclear Arms.”

The substance of the articles, most of which relied upon Associated Press copy, continued to focus on Pauling’s past controversies and suspected communism. From his lecture, the reports tended to highlight his homage to the late President Kennedy and the dollar amount of his prize. When Pauling’s policy proposals came up, mostly in larger papers that did not rely on the Associated Press, China’s admission to the United Nations and UN veto power over the use of nuclear weapons were seen as relevant and potentially controversial.

Absent from the press coverage was any discussion of the science of Pauling’s lecture. This included his claims concerning the harmful health effects of nuclear weapons as well as his descriptions of the increases in size and number of nuclear weapons. No article mentioned “genetic mutations” or “megatons” as Pauling had done in his lecture.

The Nobel medal, reverse.

One bit of critical commentary, published in the Wall Street Journal, came out a week after Pauling’s speech. Author William Henry Chamberlin dismissed Pauling’s views on peace as both unpopular and overly simplistic. Pauling’s reasoning ran counter to the thinking of all US presidents since Truman – namely, that the only avenue to peace is to make as many weapons as the Soviets. Chamberlin noted that even scientists – specifically Edward Teller – agreed.

In Chamberlin’s estimation, Pauling was merely an alarmist. Further, Pauling had no impact whatsoever on the Partial Test Ban Treaty. The idea for the treaty had emerged out of the governments of the United States and Great Britain long ago and its delay in ratification was due solely to foot-dragging from the Soviets. Chamberlin also discounted Pauling’s claim to be a representative of a world-wide movement for peace by characterizing his efforts as “a one-man crusade.”

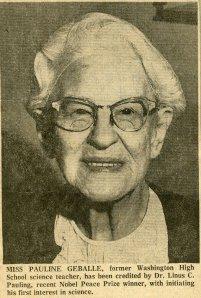

Pauline Gebelle as pictured in the Portland Oregonian, December 17, 1963.

Contrary to Chamberlin’s stance, on the same day the Portland Oregonian published a short article profiling Pauling’s freshman physiography teacher at Washington High School, Pauline Geballe. Pauling pointed to her as one who had helped to ignite his interest in science and the two had kept in touch over the years. Geballe herself, through the League of Women Voters, was also part of the peace movement. On behalf of the group, she had recently queried Pauling for insight into questions of disarmament. Pauling responded by sending her a copy of No More War! from which Geballe read aloud the next time the group met. Geballe and her colleagues seemed to evidence that, just as he had been stating for the previous two months and likewise in his Nobel acceptance speech, Pauling was merely a representative of a much larger movement, if still a polarizing and extremely prominent one.