Today is Linus Pauling’s birthday – he would have been 112 years old. Every year on February 28th we try to do something special and this time around we’re pleased to announce a project about which we’re all very excited: the sixth in our series of Pauling documentary history websites.

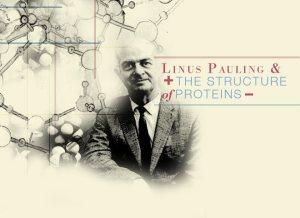

Launched today, Linus Pauling and the Structure of Proteins is the both latest in the documentary history series and our first since 2010′s The Scientific War Work of Linus C. Pauling. (we’ve been a little busy these past few years) Like Pauling’s program of proteins research, the new website is sprawling and multi-faceted. It features well over 200 letters and manuscripts, as well as the usual array of photographs, papers,audio and video that users of our sites have come to expect. A total of more than 400primary source materials illustrate and provide depth to the site’s 45-page Narrative, which was written by Pauling biographer Thomas Hager.

Warren Weaver, 1967.

That narrative tells a remarkable story that was central to many of the twentieth century’s great breakthroughs in molecular biology. Readers will, for example, learn much of Pauling’s many interactions with Warren Weaver and the Rockefeller Foundation, the organization whose interest in the “science of life” helped prompt Pauling away from his early successes on the structure of crystals in favor of investigations into biological topics.

So too will users learn about Pauling’s sometimes caustic confrontations withDorothy Wrinch, whose cyclol theory of protein structure was a source of intense objection for Pauling and his colleague, Carl Niemann. Speaking of colleagues, the website also delves into the fruitful collaboration enjoyed between Pauling and his Caltech co-worker, Robert Corey. The controversy surrounding Pauling’s interactions with another associate, Herman Branson, are also explored on the proteins website.

Linus Pauling shaking hands with Peter Lehman in front of two models of the alpha-helix. 1950s.

Much is known about Pauling’s famously lost “race for DNA,” contested with Jim Watson, Francis Crick and a handful of others in the UK. Less storied is the long running competition between Pauling’s laboratory and an array of British proteins researchers, waged several years before Watson and Crick’s breakthrough. That triumph, the double helix, was inspired by Pauling’s alpha helix, discovered one day when Linus lay sick in bed, bored and restless as he fought off a cold. (This was before the vitamin C days, of course.)

Illustration of the antibody-antigen framework, 1948.

Many more discoveries lie in waiting for those interested in the history of molecular biology: the invention of the ultracentrifuge by The Svedberg; Pauling’s long dalliance with a theory of antibodies; his hugely important concept of biological specificity; and the contested notion of coiled-coils, an episode that once again pit Pauling versus Francis Crick.

Linus Pauling and the Structure of Proteins constitutes a major addition to the Pauling canon. It is an enormously rich resource that will suit the needs of many types of researchers, students and educators. It is, in short, a fitting birthday present for history’s only recipient of two unshared Nobel Prizes.

Happy birthday, Dr. Pauling!