Natalie wrote…that she was…madly in love with a woman…[who] outstripped all her other loves by a long way. Rather vexed, I answered: “The best in your life was me! Me! Me!” - Liane de Pougy, My Blue Notebooks

Perceptive readers may have noticed that though I share a profession with the subjects of all of my harlotographies, I don’t think I would have gotten along with many of them. This is especially true of the Grandes Horizontales of La Belle Epoque; while I admire their spunk and envy their income, most of them were possessed of character traits I find irritating or even repulsive: among these are incredible irresponsibility, the tendency to use people and a pathological affection for falsehood. Though the former two would probably have caused me greater distress had I known the ladies in person, it is the latter one which annoys me most as a chronicler of whoredom because it makes it almost impossible to declare anything about their lives with certainty, despite what biographers who have never personally known a whore (much less been one) seem to believe. Case in point Liane de Pougy, whose statements about her exes (and herself) are usually reported as fact despite their conflicting with her earlier statements about the same people.

Anne-Marie Chassaigne was born in La Flèche, France on July 2nd, 1869, the daughter of Pierre and Aimée Chassaigne; like so many others of her time she was educated in a convent, but unlike most of her peers she somehow managed to evade the nuns often enough and well enough to get pregnant at 16. She eloped with the father, a young naval officer named Armand Pourpe, but predictably the marriage was both short and unhappy; she treated her baby son Marc as though he were a doll, and professed to be disappointed that he was not a girl so she could dress him up and fuss over him more. When Armand was transferred to Marseilles she remained behind and promptly took a lover, Marquis Charles de MacMahon; when her husband later caught them in flagrante delicto he shot at them but only succeeded in wounding her wrist. In response she sold her piano, abandoned her son and lit out for Paris on the first train she could catch, changing her name to “Liane” upon arrival. She later wrote in her memoirs that her husband had “taken her violently on their wedding night”, supposedly traumatizing her; consider, however, that she was already sexually involved with him before they were married, and that this supposed emotional shock didn’t stop her from having sex with someone else as soon as he was over the horizon. Furthermore, her arch-rival La Belle Otero claimed to have been raped at ten; one must wonder if Liane didn’t invent her marriage-bed ravishment so that she, too, could have a sexual horror story for those who responded to that sort of thing. She also claimed that her husband was a brute who beat her, and that she had a scar on her breast from one such beating; perhaps, but it also provided a convenient excuse for her infidelity.

Anne-Marie Chassaigne was born in La Flèche, France on July 2nd, 1869, the daughter of Pierre and Aimée Chassaigne; like so many others of her time she was educated in a convent, but unlike most of her peers she somehow managed to evade the nuns often enough and well enough to get pregnant at 16. She eloped with the father, a young naval officer named Armand Pourpe, but predictably the marriage was both short and unhappy; she treated her baby son Marc as though he were a doll, and professed to be disappointed that he was not a girl so she could dress him up and fuss over him more. When Armand was transferred to Marseilles she remained behind and promptly took a lover, Marquis Charles de MacMahon; when her husband later caught them in flagrante delicto he shot at them but only succeeded in wounding her wrist. In response she sold her piano, abandoned her son and lit out for Paris on the first train she could catch, changing her name to “Liane” upon arrival. She later wrote in her memoirs that her husband had “taken her violently on their wedding night”, supposedly traumatizing her; consider, however, that she was already sexually involved with him before they were married, and that this supposed emotional shock didn’t stop her from having sex with someone else as soon as he was over the horizon. Furthermore, her arch-rival La Belle Otero claimed to have been raped at ten; one must wonder if Liane didn’t invent her marriage-bed ravishment so that she, too, could have a sexual horror story for those who responded to that sort of thing. She also claimed that her husband was a brute who beat her, and that she had a scar on her breast from one such beating; perhaps, but it also provided a convenient excuse for her infidelity.

In Paris, the 18-year-old Liane immediately set out to become a courtesan, and learned the trade from the highly-respected Countess Valtesse de la Bigne. Much to her mentor’s annoyance, Liane was bored by intellectual pursuits, but she was simply more attuned to the zeitgeist than the older woman: it was a time when appearance and style were prized over depth and substance, as evidenced by the fact that, though utterly devoid of any acting talent, she was hired to headline a show at the Folies-Bergere on the basis of the impression she had made while attending the Grand Prix with the Vicomte de Pougy (whose surname she promptly appropriated). So hopeless was she that Sarah Bernhardt, who had been given the job of teaching her to act, eventually told her, “when on stage, just keep your pretty mouth shut.” But as with so many others up to the present day, this did not stop her from becoming a wildly popular celebrity; it started on the night of her debut, when she picked up the visiting Prince of Wales as a client.

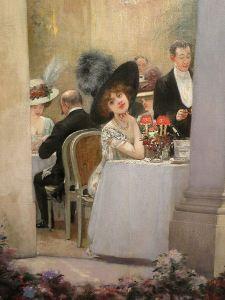

The ‘90s were the heyday of Liane’s career and the period of her infamous rivalry with La Belle Otero, played out in the various theaters and the dining room of Maxim’s restaurant, a favorite of the demimonde. Though Otero became more famous and sought-after than de Pougy by about 1895, Liane was the wiser investor and the more careful bookkeeper, and appears to have had a larger number of less-famous clients compared with Otero’s smaller number of kings and princes. Both women derived a sizeable secondary income from licensing their images for postcards, as was typical for courtesans of the time; as I have noted before, this period saw the beginning of the modern cult of celebrity, and the Grandes Horizontales were at the center of it.

The ‘90s were the heyday of Liane’s career and the period of her infamous rivalry with La Belle Otero, played out in the various theaters and the dining room of Maxim’s restaurant, a favorite of the demimonde. Though Otero became more famous and sought-after than de Pougy by about 1895, Liane was the wiser investor and the more careful bookkeeper, and appears to have had a larger number of less-famous clients compared with Otero’s smaller number of kings and princes. Both women derived a sizeable secondary income from licensing their images for postcards, as was typical for courtesans of the time; as I have noted before, this period saw the beginning of the modern cult of celebrity, and the Grandes Horizontales were at the center of it.

Like most courtesans, Liane began to opt for longer-term arrangements as she aged; unlike most, not all of hers were with men. In 1899 the American heiress and writer Natalie Clifford Barney became infatuated with her after seeing her at the Folies-Bergere, and though their lesbian relationship was very intense it was also very short because Barney kept insisting she wanted to “rescue” Liane from prostitution (a notion much more popular in America at that time than in France). The two continued to have deep feelings for one another, though, and corresponded for the rest of their lives (see epigram). Never one to miss a moneymaking opportunity, in 1901 Liane published a thinly-fictionalized account of their affair, Sapphic Idyll, which became a runaway bestseller and caused Barney considerable trouble with her straight-laced parents. She also profited in another way: when it became known that she was bisexual, she gained a small but profitable upper-class lesbian clientele.

On June 8, 1910 the almost-41 Liane married the notably-younger Prince Georges Ghika, after which she was called Princess Ghika. Though neither as rocky nor as short-lived as her first marriage, this one was not without its major difficulties; the first of these came on December 2nd, 1914 when her son Marc, a French pilot in the First World War, was killed in action near Villers-Brettoneux. Though she had never been close to him, his death precipitated a period of soul-searching in which she turned back to the Church, becoming a lay Dominican sister. Though this phase did not last long, she remained devout for the rest of her life (though like many Catholics, she ignored sexual prohibitions she found inconvenient). In 1926 Ghika ran off with a much younger woman, and while Liane’s diaries of the period brand him a pervert (whereas before he was described in glowing terms), the two did not divorce. She consoled herself with lesbian lovers until he came back to her a few years later, and they remained together until his death in 1945; the latter period was not a happy one, however, and each had a series of extramarital girlfriends.

On June 8, 1910 the almost-41 Liane married the notably-younger Prince Georges Ghika, after which she was called Princess Ghika. Though neither as rocky nor as short-lived as her first marriage, this one was not without its major difficulties; the first of these came on December 2nd, 1914 when her son Marc, a French pilot in the First World War, was killed in action near Villers-Brettoneux. Though she had never been close to him, his death precipitated a period of soul-searching in which she turned back to the Church, becoming a lay Dominican sister. Though this phase did not last long, she remained devout for the rest of her life (though like many Catholics, she ignored sexual prohibitions she found inconvenient). In 1926 Ghika ran off with a much younger woman, and while Liane’s diaries of the period brand him a pervert (whereas before he was described in glowing terms), the two did not divorce. She consoled herself with lesbian lovers until he came back to her a few years later, and they remained together until his death in 1945; the latter period was not a happy one, however, and each had a series of extramarital girlfriends.

After his death she re-entered the Dominicans permanently as Sister Anne-Marie, and spent her last five years caring for physically and mentally handicapped children; she died at the Asylum of Saint Agnes in Lausanne, Switzerland on December 26th, 1950, at the ripe old age of 81. Her memoirs, My Blue Notebooks, were published posthumously. Though many who wish to believe in such things have praised the “repentance” for her “sinful” past (most especially her prostitution and lesbianism) she proclaims in this work, the more cynical eye of this harlot sees instead the pièce de résistance of a long series of deceptions. While her previous writings merely reinterpreted other people in her life, this one reinvented herself; and while the others were only intended to deceive mere mortals, this one was designed to pull the wool over the eyes of God himself. And no matter what else I feel about her, I have to admire her for that one, grand, final act of chutzpah.