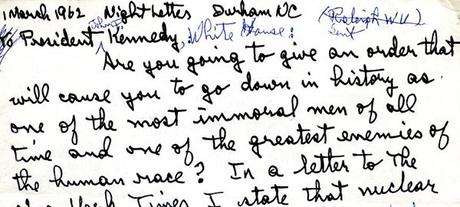

Excerpt from Pauling’s “night letter” to John F. Kennedy, March 1962

Excerpt from Pauling’s “night letter” to John F. Kennedy, March 1962[With this post, we begin an examination of Linus Pauling’s relationship with President John F. Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khruschev during tense times. This is part 1 of 3.]

The private relationships that Linus Pauling maintained with U.S. President John F. Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev were surprisingly similar, despite the fact that the two figureheads were personally very different, and that they represented highly divergent values and interests. For Pauling however, both men were key proponents of testing nuclear weapons, and because of that, both needed to be lobbied to work toward disarmament.

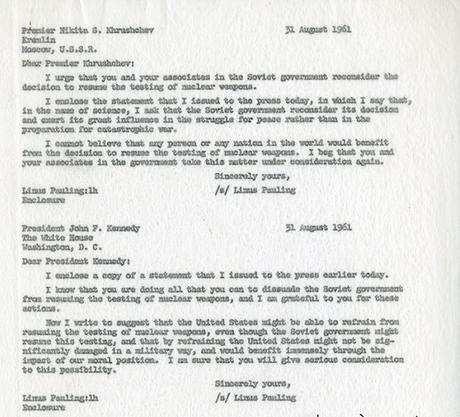

In the few short years that the Kennedy and Khrushchev administrations overlapped, Pauling wrote to both men relentlessly, urging each to stop testing nuclear weapons. The tone with which Pauling addressed both men was nearly identical, cementing the fact that Pauling viewed this issue as being of the utmost importance. However, the response and subsequent correspondence between Pauling and the two world leaders differed markedly.

Pauling and Khrushchev corresponded frequently on the topic of disarmament, even agreeing, at times, about the need to do more. Kennedy, on the other hand, never formally responded to Pauling’s pleas, though he did seem to want to enlist Pauling as a science advisor and even an ally. Nothing of the sort ever materialized, though the two did engage socially.

Ultimately the story of Pauling, Kennedy and Khrushchev is one of Pauling’s enduring activism and perseverance, even in the face of generally indifferent responses to his warnings of doom and demise. While this series will explore his communications with both leaders, today’s post focuses more intently on Kennedy.

At multiple points during the Kennedy presidency, Pauling sent letters pleading that the United States cease its nuclear testing program. Often these letters were prompted by Kennedy’s public rhetoric surrounding nuclear issues. On November 11, 1962 for example, Kennedy made a public address to veterans at Arlington National Cemetery where he commented on the state of affairs, suggesting that, “The only way to maintain peace is to be prepared in the final extreme.” In a printed edition of Kennedy’s speech, Pauling scrawled this particular passage in the margins, and then wrote in large block letters that “SUCH A POLICY WILL MEAN THE END OF CIVILIZATION.” For Pauling, clearly, this was not merely rhetoric; this was the potential end of life on Earth.

The speech prompted Pauling to write a “Night Letter” to Kennedy, with copies sent to several of his scientific advisors. In it, Pauling offers Kennedy a stark choice: either stop the American testing program or “go down in history as one of the most immoral men of all time and one of the greatest enemies of the human race.” Pauling based his argument on his calculation that the Carbon-14 fallout from continued testing would be the source of birth defects for more than 20 million children yet to be born. Accordingly, were Kennedy to continue down this path, he would personally be “guilty of this monstrous immorality, matching that of the Soviet leaders.”

This incendiary tone was perhaps extreme, but certainly characteristic of the peril that Pauling sought to emphasize in his Kennedy letters. In a different exchange, Pauling criticized a series of interviews that Kennedy had given to LIFE magazine in which he seemed to represent nuclear radiation as being relatively benign. For Pauling, statements of this sort would only “have the effect of increasing the danger to our nation and to the American people.” Kennedy’s response, as authored by National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy, implied that the LIFE article had taken the President out of context and was not representative of his actual views. Regardless, the interview had already been published and the proverbial damage was done.

Ava Helen Pauling, by now a high profile activist herself, took a different tack from her husband. Instead of excoriating Kennedy for his decisions, Ava Helen wrote that he could potentially “become the greatest president that the United States has ever had” were he to successfully end the testing of nuclear weapons.

She also wrote a letter to the first lady, Jacqueline Kennedy, issuing a plea on behalf of the health and safety of the world’s children. In the letter, Ava Helen leaned heavily on a “mother to mother” connection, while painting a decidedly grim portrait. Absent a ban on nuclear tests, Strontium-90 would continue to build up in the bones of children and create all manner of ill health effects. Though it may seem rash, Ava Helen urged the first lady to support what she believed to be a sensible path in pushing for a test ban treaty.

President Kennedy, of course, was not the only person who needed to be held accountable for nuclear weapons testing. In Pauling’s mind, nothing of consequence would happen unless both Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev came to mutual agreement.

At various points – and in a somewhat literal manifestation of their equal status in Pauling’s mind – Pauling drafted letters to both Khrushchev and Kennedy on the same piece of paper. On other occasions, Pauling chose to question the leaders’ motivations. Notably, in 1962 Pauling sent a telegram to Kennedy urging that he end nuclear testing in the United States. In it, Pauling also insisted that the testing that Kennedy had already approved had not been driven by Khrushchev’s actions – a motivation that Kennedy had publicly declared – but rather because he was “forced by the U.S. militarists, the military-industrial complex” to do so. Nuclear testing then, was nothing more than an extension of a longer striving for military superiority and power. In Pauling’s view, this was deeply immoral and wholly unacceptable.