John Thacker's 1758 Marrow Pudding or Poudin de Mouëlle formée with its ornate cut cover

A few days ago a researcher working on a TV bakery programme rang to say that she wanted 'to pick my brains' about 'the history of latticework tarts', as Google and Wikipedia had not furnished any revelations on the subject. Funnily enough I had just filmed a short feature for a rival baking programme on puff pastry, in which I made the elaborate decorated lid for the baked pudding pictured above. So the subject was topical. Dishes like the good old 'criss-cross' jam tart of modern England and the crostata of Italy have a venerable and surprisingly sophisticated history. In fact many made in the past were very much more ambitious than those I have seen coming out of the ovens of modern bakers.The great heyday of this kind of pastry trellis work lasted from the second half of the sixteenth century to the first half of the eighteenth. It almost certainly had its origins in a burgeoning fashion for knotted strapwork ornament inaugurated by Mannerist architects such as Sebastiano Serlio (1475-1554). Interlacing decorations like those published by Serlio found their best known expression in architectural detailing and garden design, but food ornamentation was strongly influenced by the same zeitgeist. The curious knotted biscuits or sweetmeats known as jumbals emerge at this period and elaborate tarts and pies in kaleidoscopic knot-garden form start to adorn the the tables of the wealthy. Strap work was all the rage.

A plate of sixteenth century sweetmeats I made for Francis Drake's house at Buckland Abbey about fifteen years ago. The knotted biscuits are jumbals. All were copied from Netherlandish paintings of period.

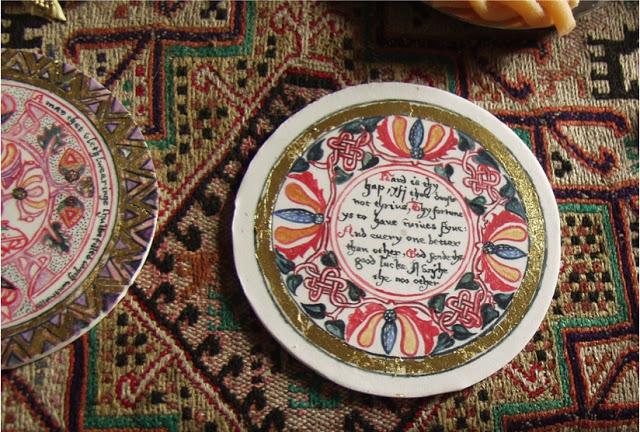

Another expression of strapwork on the English table were designs painted on banqueting trenchers in the second half of the sixteenth century. Sometimes as here, these were made out of sugar paste and painted with edible colours. I made these sugar copies of some Tudor originals for a table display I created for Chatsworth House about eight years ago. |

A table setting by the Antwerp artist Clara Peeters (1594 – c. 1657), including a pastry with a cut design, c. 1611, oil on panel. Museo del Prado, Madrid. Nothing to do with lattice work pastry, but note how Clara has painted the spit roast birds with their livers tucked under their pinions.

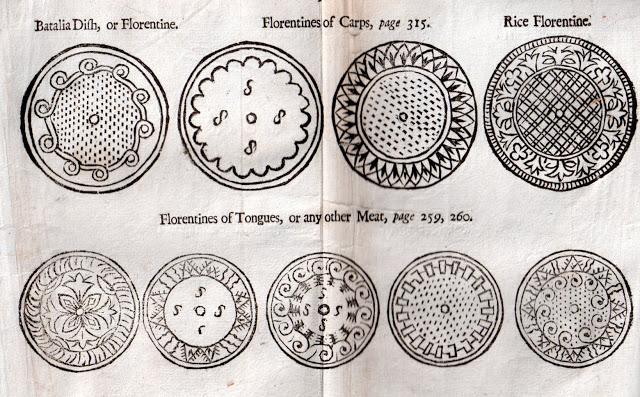

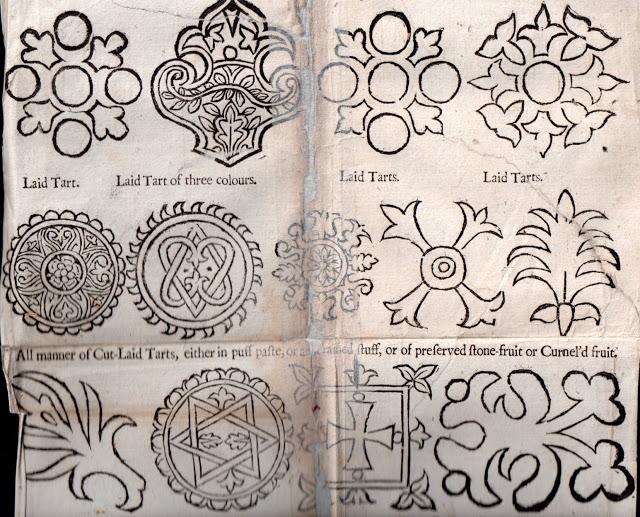

When they did appear (with one major exception) they were exclusively to be found in English cookery texts. The designs below for Florendines are from Robert May's The Accomplisht Cook of 1660. Florendines were shallow pies filled with various kinds of meat or fish. May was not quite the first European cook to offer us designs for pastry ornamentation of this kind, as another Englishman, Joseph Cooper had included a few crude woodcuts of pie shapes in his The Art of Cookery Refin'd and Augmented (London: 1654). But May was the first to publish a wide variety of designs for different pastry types. Although they are quite crude, his woodcuts give us an insight into the extraordinary lengths that pastry cooks went to in high status houses in baroque England.

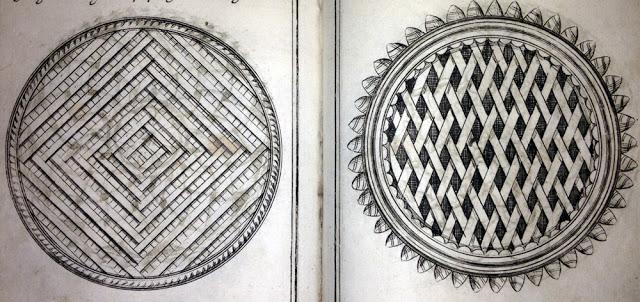

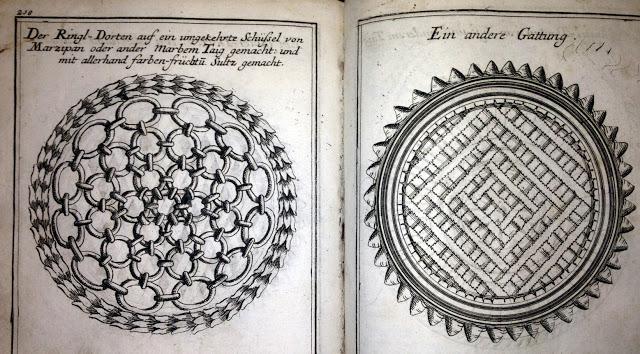

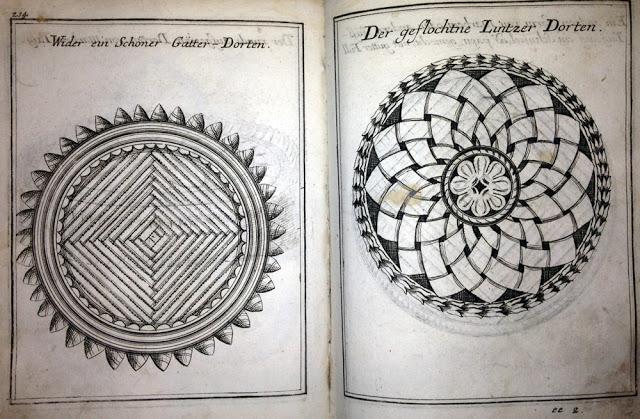

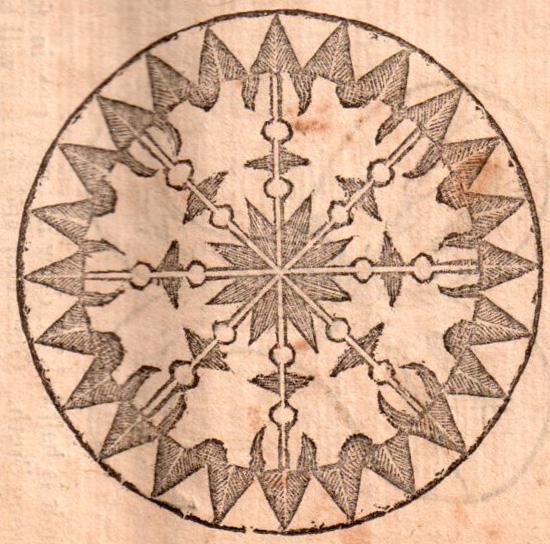

Other than a handful of English cookery books from the seventeenth and early eighteenth century, no other European printed texts contain designs like those of Robert May. Apart that is, from one notable exception from Austria, Conrad Hagger's Neues Saltzburgisches Kochbuch (Augsburg: 1719). This magisterial collection of recipes occupies a full horizontal five inches of my bookshelf and is one of the most important books I own. I often marvel at my good fortune, as I was lucky enough to buy a copy of this rare work in Liechtenstein for $50 in the 1970s! No other cookery text allows us such a detailed insight into the pastry techniques of the baroque Hofkoch than Hagger's work. Its 305 full plate engravings provide a bewildering variety of designs for pies, pasties, marchpanes and torts. Here are some of his variations on the lattice work tart.

Lattice work pastry designs from Conrad Hagger, Neues Saltzburgisches Kochbuch (Augsburg: 1719)

Hagger's designs are very similar to those in May's book, but offer us far more detail. They indicate that the culinary expectations of his master Franz Anton von Harrach (1665-1727), the Prince Archbishop of Salzburg from 1709-1727, must have been very demanding. However, food in the Archbishop's palace appears to have been somewhat conservative and old fashioned. Elements of of the new French cookery style are present in Hagger's book, but many of his pie designs hark back to the previous century. Though he was an old man when he wrote his book and was probably documenting the cookery style of his heyday. Ecclesiastical households were much more conservative than princely ones and appeared to favour the old style of cookery. This is also apparent in the work of the English ecclesiastical cook John Thacker, who worked for the dean and chapter of Durham Cathedral between 1739 and 1758. Thacker's book The Art of Cookery (Newcastle upon Tyne:1758) was the last of the baroque recipe collections to contain illustrations of pastry work. Here is his design for a cover for a marrow pudding.

Covers like this were usually made out of puff pastry and were usually baked separately from the tart or pudding they adorned. Here is my interpretation of Thacker's design sitting on a sheet of paper on a baking tray and ready for the oven.

Thacker's cut lid baked and dusted with icing sugar

Thacker gives no instructions for doing this, butIcould not resist dusting the pudding with powdered sugar and then removing the lid

Nearly a century earlier Robert May had published directions and diagrams for making cut lids of this kind. The shapes between the pastry 'slips' were designed to be filled with coloured preserves and fruit pastes, making some of them the most colourful baked goods in the history of English food.

Robert May's designs for cut laid tarts

The cut laid tarts above based on May's designs were all made for my exhibition Supper with Shakespeare at the Minneapolis Institute of the Arts in 2012.

A strap work tart sits in front of a sugar paste banqueting house at the MIA exhibition

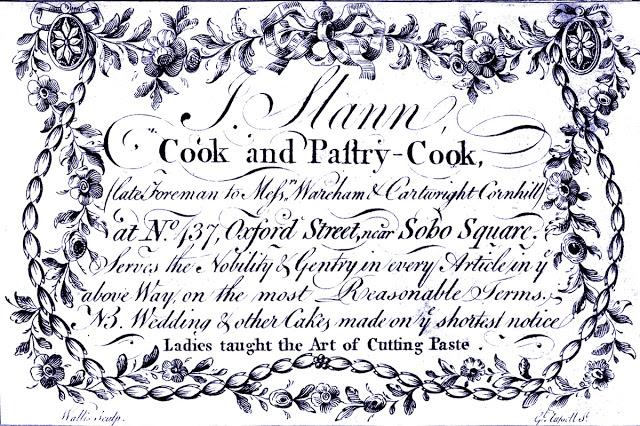

Cut pastry continued to be popular well into the eighteenth century. One kind that emerged was the 'crocant', a technically difficult genre which involved placing a sheet of a special crocant past over a domed mold and then cutting it by hand with decorative designs in the form of leaves, birds, animals etc. They were baked on the domed moulds. When finished crocants often iced and then placed over plates of colourful sweetmeats. We will never know what these ephemeral creations looked like, because no designs have survived, though ceramic manufactories such as Wedgewood and Royal Copenhagen produced pierced lids for vessels which may have been influenced by these edible cut covers. However, we can be sure that standards were incredibly high and there were quite a lot of professional bakers who were prepared for a fee to instruct ladies in the art of cutting designs like this in pastry.

Many of the professional London pastry cooks offered instruction in 'cutting paste'