Lance Henriksen: A Survivor’s Tale

By Alex Simon

A seminal event happened to actor Lance Henriksen in his late teens that serves as the perfect metaphor for his life: Henriksen was working at a rural New Mexico gas station, and was taken in by the couple who owned it. They had a teenage daughter a couple years his junior. One day, figuring Lance and his daughter were getting a bit too chummy; the man drove Henriksen out to the middle of the desert. “All winter long, the frost has been pushing up these beautiful amethyst stones,” the man explained. “I’ll drop you off and you can collect them, then come back and sell them for a lot of money.” Henriksen stayed half the night, and then started to succumb to the desert’s freezing temperatures. “I dug a hole and buried myself up to my chest, with a fire in front of me. My fucking eyebrows were getting scorched…I was thinking: ‘This is not good.’ In the dark, I could see lights in the distance. I got up and hitchhiked out of there.”

Henriksen was born into “an extremely dysfunctional family” May 5, 1940 in New York City. His father was a Norwegian merchant sailor and boxer nicknamed "Icewater" who spent most of his life at sea. His mother, Marguerite, struggled to find work as a dance instructor, waitress, and model. His parents divorced when he was two years old, and he was raised by his mother. As he grew up, Henriksen found himself in trouble at various schools and even saw the inside of a children's home. Henriksen left home and dropped out of school at twelve, living a gypsy’s life of travel and survival by any means necessary. He didn’t learn to read until he was thirty, which he taught himself to do by studying film scripts. He made his uncredited film debut in John Frankenheimer’s TV-movie The American, in 1960, as an extra in a Yuma, AZ. prison where, coincidentally, he was locked up at the time for vagrancy.

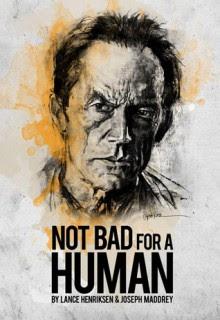

Over 100 films later, Lance Henriksen has become one of cinema and TV’s most recognizable faces and has worked with filmmaking legends such as Sidney Lumet (three times), James Cameron (three times), John Woo, Walter Hill, Steven Spielberg, Jim Jarmusch and many more. Henriksen published his autobiography, Not Bad for a Human (co-written with Joseph Maddrey), in 2011, through Bloody Pulp Books. His latest film, one of fifteen being released this year, along with an appearance on TV’s The Blacklist, is Alec Gillis’ Harbinger Down, a sci-fi/horror thriller about grad students who foolishly unthaw some frozen, aged Soviet space wreckage, also reviving the mutant creatures who hitched a ride. Gillis, a former Stan Winston effects technician, provided lots of old school thrills and gore, with Henriksen offering another riveting turn to add to his canon. It arrives in limited theatrical release and on VOD Friday, August 7.

Lance Henriksen sat down with us recently to discuss his remarkable life and career. Here’s what transpired:

On himself:

I don’t really have an identity, I really don’t. I spend half my life living other people’s lives. I kind of rationalize everything that happens in my life, and make it personal. It’s a crazy phenomenon.

I am a survivor. There’s an old saying: “If you can’t use it, lose it. If you can’t lose it, use it.”

On Harbinger Down:

I’ve known (writer/director) Alec Gillis for 30 years. He’s good people. I’ve been telling him all that time ‘Look man, you know how to do all this, why don’t you make your own film, instead of being in service to other people’s films?’ And that’s exactly what he did. It’s a homage to all the great ‘80s horror films.

On filmmaking:

There’s no difference for me between big budget and low budget filmmaking. I’m there to conspire with the cast and crew to make the best movie we can.

On watching John Frankenheimer’s The American being filmed around him when he was in jail:

I felt like they were an elite force, who could get away with anything and maybe they could scoop me up and take me out of there. I mean, to be able to do wheelies in the middle of an intersection with a Chevy and get away with it, but to get paid for it? That was for me.

On his brief encounter with Lee Marvin, during The American.

I talked with Lee Marvin for about 30 seconds. He looked at me, “What’re you doin’ here, kid?” I said, “Trying to get out!” (laughs)

On his education:

I left school after the eighth grade. I was already an artist. I had a sense of what I loved, but life got in the way.

Lance Henriksen in Harbinger Down (2015).

Lance Henriksen in Harbinger Down (2015). On the arts:

The arts have a way of opening a door into a different kind of thinking, and that’s what saved my life, the arts.

On working with talented people:

I’ve been lucky enough to cross paths with some of the best people in the arts. They made me realize this is not a dress rehearsal, this is all we’re gonna get. If I hang out with gangsters, I’m gonna be in trouble.

On The Actors Studio:

I wandered into The Actors Studio as a kid, and there was Rod Steiger standing at the desk, looking like a big, pink gorilla. I walked up to the receptionist, and could barely speak, I said: (whispers) ‘I wanna be an actor.’ She sneered at me: “You’re too young. Get outta here!” So I did and didn’t come back for twenty years.

On acting guru Sanford Meisner:

Jon Voight sent me to see Sanford Meisner, “Just go talk to him, man!” Jon’s got a heart as big as a baby’s head, he really does. Then Meisner pulled this attitude with me and I thought to myself ‘This is everything I don’t like.’ Had he been a regular guy with me, I would have said ‘Okay, there’s a place for me here.’

In Sidney Lumet's Dog Day Afternoon (1975).

In Sidney Lumet's Dog Day Afternoon (1975). On Sidney Lumet:

I did three movies with Lumet and he was the only guy in the industry I’ve ever seen who worked this way: he’d get the entire cast together, big parts and small, rent out this big ballroom, tape off all the locations, and we’d do the whole script with everyone there, block it out. Then by the time we got to the set, not only was everyone comfortable, but we were an ensemble.

On reading the script of Aliens for the first time:

When I first read it, I remembered the opening line being “Space: like the love of God, cold and remote.” I found my script years later, opened it up and that line wasn’t there. Where the hell did that come from? (laughs)

On working with Francois Truffaut on Close Encounters of the Third Kind:

The first time I saw The 400 Blows, I was just devastated by it, because it was like my story, exactly. At the end of (Close Encounters), there was a package in my trailer. I opened it and it was the script to The 400 Blows. Truffaut inscribed it to me “You are now, and always will be, this kid.”

L to R: Francois Truffaut, Bob Balaban, Steven Spielberg and Lance Henriksen on the Close Encounters set, 1977.

L to R: Francois Truffaut, Bob Balaban, Steven Spielberg and Lance Henriksen on the Close Encounters set, 1977. On Steven Spielberg:

Spielberg was a very young guy then, late twenties. We were in Wyoming, standing on the side of the road with Devil’s Tower in the background, when he got a call from his accountant. Steven turned to me, so excited, and said “I’m a millionaire!” I was like, ‘That’s great, Steven. Thanks for sharing. Now I feel like a fuckin’ pauper.’

On the Close Encounters shoot:

I had an idea for the ending that I shared with Steven: I wanted to capture one of the little aliens, throw my jacket over him and hide him in one of the porta-potties. He just looked at me and said “Lance, that’s a different movie.” I was relieved because I thought he was gonna say “Lance, time for you to go home.”

On James Cameron:

There’s nobody else quite like Jim Cameron. There may be guys who are more charming, but I know the core truth of who he is: by the time the movie is ready to shoot, he has written and re-written the script over and over until it’s perfect. He also knows that once you arrive on that soundstage, this is only shot you’re going to get at what you’re doing, so he works till he drops. He’s the first guy on the set and the last to leave. That’s Jim Cameron: a magnificent obsession.

Clockwise: Lance Henriksen, Scott Glenn, Scott Paulin, Fred Ward, Charles Frank, Dennis Quaid and Ed Harris in The Right Stuff (1983).

Clockwise: Lance Henriksen, Scott Glenn, Scott Paulin, Fred Ward, Charles Frank, Dennis Quaid and Ed Harris in The Right Stuff (1983). On playing Wally Schirra in The Right Stuff:

I was very unhappy with how The Right Stuff turned out. Phil Kaufman did it as a satire, and I thought the Mercury astronauts were heroes, not “spam in a can.” I was very outspoken about it when the film came out, and I don’t think Phil ever forgave me. Gordo Cooper and I became very good friends afterward, and he was my advisor on a screenplay I wrote about space travel. I hope I can get it made some day.

On a spooky experience with Uma Thurman:

We were shooting Jennifer 8 in an old asylum in Vancouver, BC. It was used to house the insane and people with extreme cases of syphilis. Uma and I walked up to the top floor and found this room that all white tile, floor to ceiling. It was huge. We took a Ouija Board with us. We asked it “Who killed Kennedy.” And the thing whipped out of our hands, and kept spelling “LBJ” over and over. We asked “Who are you?” The response: “I’m the guy who did it. They locked me away here, because I knew too much.” Boy, did we get the hell outta there fast!

As the android Bishop in James Cameron's Aliens (1986).

As the android Bishop in James Cameron's Aliens (1986). On inhabiting a character:

Sometimes if I’m playing a really dark, evil character, he’s tough to shake. I purposefully isolate myself, because I can’t be around other people. And it’s very lonely. John Woo told me after we wrapped Hard Target, “Lance, I want you to play a good guy next time. I was really worried about you.”

On his work ethic:

I’ve been lucky enough to rub elbows with some of the best, just amazingly talented people. That changes you. It’s like Lone Survivor: you’re working with the people that are next to you. It’s not about the big scheme of things. I’m not trying to make this giant movie. I’m just trying to make this work.

On pottery:

I make pottery, and I don’t mean like high school stuff. I have a five thousand square foot studio that I make pottery in. That’s all I do when I’m not working. It has nothing else to do with anything else in the world. It’s just me and the labor. It grounds me. I’m going to do a documentary about it for Discovery Channel, although they don’t know it yet, called Lick My Bowls. We have one of the greatest art forms in the world here, and no one gives a shit about it. I’m gonna change that.

A final thought on Harbinger Down:

The whole point of the movie is practical effects. The other aspect is that we can create it all, either through miniatures, building the sets together, keeping it old school. People were coming out of nowhere to help out. Guys who worked for Chrysler designing cars were showing up to work on the set for free. Everybody was on the same track. Alec and Tom Woodruff have always been generous with the people they’ve worked with and the payback was what went into making this film.