Lab Wars Interview

This is an unusual post for the blog because it’s primarily an audio interview. Following the interview are some musings on why board games are fun, why boardgames appeal to nerds, and whether playing games can make you smarter.

I just finished recording and editing an interview with charming Caezar Al-Jassar, Ph.D, co-creator of the game Lab Wars. The conversation goes into having a side project as a young academic and Caezar’s kickstarter success, but also touches on heavier topics such as the difficulties of imposter syndrome, and leaving the academic bubble and trying to make it in the real world. I haven’t gotten a chance to play Lab Wars yet, but it’s gotten good initial reviews on Board Game Geek.

To subscribe to Neuroamer audio content in podcast form, click here.

Other games we discussed in the interview audio (which might make a great gift for a nerd you love this holiday season, hint hint, Mom). [Mom, if you actually read this that was just a joke]

Dominion: the first deck-building game ever and one of my all-time favorites.

Evolution: Haven’t played this but it looks rad and has great ratings on Board Game Geek.

Viticulture: Same as above.

Pandemic: the best science-themed game I’ve played. You play as different scientists and public health officials at the Center for Disease Controls, working collaboratively to try to prevent a pandemic from wiping out humanity. If you’re looking to play an interesting and challenging game where you work together as opposed to fight against one another, this is my top recc.

—

Why Are Board Games Fun?

As a child, I sunk a lot of time into all kinds of games: Sierra Adventure Games, Magic the Gathering, Chess, Dungeons and Dragons, and Catan. When I worked as a tech at MIT, I played a lot of “German-style” board games — games that are more skill and strategy-based than the American classics like Monopoly — for example: Puerto Rico, Power Grid, and Seven Wonders

One thing that fascinated me then, that I still haven’t figured out, is what makes board games — particularly intricate games with lots of rules — fun to nerds like me? I hate complicated sets of rules in real life: bureaucracy, taxes, etc., so why is sitting down with a group of friends at a nice table, tearing the shrink wrap off of a new game, and starting in on the rulebook so fun?

I’m not sure, but a large part of the fun for me is that they are inherently understandable. Games are self-contained worlds that you can escape into. You know the rules, you know the objective, and you can take your time with your decisions, and there’s something deeply satisfying about making the objectively correct decision in a given situation.

I think another aspect that drives many games is a degree of luck, which is appealing in two ways. First, as I joke In the interview, I believe a game with both skill and luck allows the winner to attribute his success to superior skill and the losers to blame their bad luck. Randomness facilitates the self-serving bias we have in all aspects of life, where we ascribe success to their own abilities and efforts, but ascribe failure to external factors. Second, and more cynically, I think the randomness in games also is rewarding in the same way gambling or watching sports is.

Why Do Board Games Appeal To Nerds?

Another question, is why are certain people drawn to these games? In my life it seems like the smartest people I knew, and many academically successful people were drawn to board games and games of that ilk. One explanation is that the nerdy nature of games repels some people from trying them or getting into them, but many of my friends and I got into these kinds of games at ages we didn’t realize they had stigma or where symbolizers in a bigger culture.

Certainly the themes of many games fall into the mainstay genres of geekdom, fantasy and science fiction, but I think there’s something more to it than that. I remember showing up for the first time at a magic the gathering even as an adult–people went around the room and listed their careers: literally every person was a computer programmer, lawyer, or graduate student. Given this was Cambridge, MA, and a self-selecting group, but I think there’s something to it.

Maybe I’m looking at the causation backwards: do nerds play games, or do games make nerds?

Can Playing Games Make You Smarter?

Recent controversies over brain training games that were specifically designed to enhance cognition, highlight the fact that learning one task generally does not ‘transfer’ any benefit to other tasks, even highly-related ones.

For example, classic studies showed, unlike what you might expect, elite chess players are no better than novices at memorizing chess boards with randomly arranged pieces. However, they are significantly better at memorizing chess boards with the pieces in positions that you might encounter during an actual game. The theory goes that actual board pieces contain commonly-encountered groups of pieces — For example a castled King on the last row with three pawns in front. Whereas a novice takes stock of these pieces individually, the expert ‘chunks’ them and can remember them as a whole unit, freeing space for him to memorize other pieces on the board.

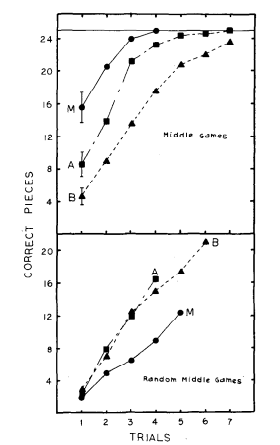

Learning curves of the master ( M ), class A player (A), and beginner (B) for the middle-game and random middle-game positions. The brackets are standard errors on five positions. From Chase and Simon, 1974

This is a fascinating example of the psychological ‘chunking,’ but also a dismaying evidence that playing chess does not improve general visual memory and consistent with the ‘lack of transfer’ between tasks, in this case because the learning through ‘chunking’ is so specific to chess.

For children, I can’t decide if they’re just time sinks or if they still manage to teach something. Certainly Magic and D&D helped me with my basic arithmetic and vocabulary — ask me what a maine-gauche is, I dare you! But seriously, I did read a lot of manuals, and learned useful words like charisma or encumbrance

But on the other hand I’ve also devoted enumerable synapses to remembering trivia such as: “Mons’s Goblin Raider is 1/1 red goblin creature.” And despite the important lesson it provided on the proper use of apostrophes, everything has an opportunity cost. Games are probably better than sitting in front of a TV, but would I have been better off playing outside or learning a real skill like playing an instrument? I’m not sure.

Finally, despite studies showing a lack of transfer, intuitively I do feel like these games honed my ability to think logically. You have to consider many decisions, by holding a bunch of rules in your head, and considering the outcome of applying cause-and-effect rules in strict order. Only after you make your decision you can reason what will happen out loud and check it with the other players. This abstract skill seems very valuable for the exact group of people I met playing Magic Cards in Cambridge: programmers, scientists, and lawyers — people who have to follow rules, whether they are the rules of board game, a programming language, physics, or law.

—

If you like the interview or the article, please share! Maybe someone who listens/reads will buy you one of these games :p