[Guest post written by John Leavitt, Ph.D., retired Senior Scientist at LPISM in Palo Alto CA from 1981 to 1988; living in Woodstock, CT. Leavitt has contributed several posts to the Pauling Blog in the past, all of which are collected here.]

John Leavitt

On August 24, 2016, the New York Times summarized the results of a Phase 3 clinical study of 6693 women with breast cancer. The outcome of this extensive clinical study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine on August 25, 2016. The clinical trial had been initiated ten years earlier on December 11, 2006 in Europe, (2005-002625-31) and on February 8, 2007 in the United States (NCT00433589). The study examined seventy select genes (seventy breast cancer “signature genes”) out of approximately 25,000 genes in the human genome that, when assayed *together* using a high density DNA microarray, predict the need for early chemotherapy.

In other words, the study asked which of the 6,693 tumors were “high risk” and likely to metastasize to distant sites within a five-year period, and which of these tumors were “low risk” and likely not to metastasize to distant sites in five years. One stated purpose of the study was to determine the need for chemotherapy, which can be very toxic and cause unnecessary harm to the patient, in treating breast cancer. The study found that a certain pattern of elevated or diminished expression of the seventy signature genes can predict a favorable non-metastatic outcome without chemotherapy for five years (while undergoing other forms of therapy such as surgery and irradiation).

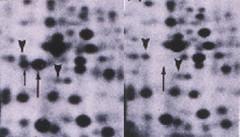

One of the seventy selected genes is L-plastin (gene symbol “LCP1” and identified by the blue arrow in the figure below).

In 1985, my colleagues and I identified this protein in a cancer model system and named it “plastin” (Goldstein et al., 1985). We cloned the gene for human plastin while at the Linus Pauling Institute of Science and Medicine in 1987, and discovered that there were two distinct isoforms encoded by separate genes, L- and T-plastin (Lin et al, 1988). In 2014, in a piece published on the Pauling Blog, I described in some detail the discovery of L-plastin and its subsequent cloning.

A second figure, which is included below, summarizes information about L-plastin in a gene card published by the National Center for Biotechnology Information. This card shows that “LCP1: is the gene symbol for L-plastin and also identifies alternative names for L-plastin. Except for the inappropriate expression of L-plastin in tumor cells, this gene is only constitutively active in white blood cells (hematopoietic cells of the circulatory system). We used very sensitive techniques to try and detect L-plastin in non-blood cells such as fibroblasts, epithelial cells, melanocytes, and endothelial cells, but could not detect its presence in these normal non-hematopoietic cells of solid tissues.

The L-plastin gene card.

The clinical study reported on in the New York Times and New England Journal of Medicine shows that if L-plastin is not elevated in synthesis and modulated in combination with other signature genes, there should be little or no metastasis in five years. However, if L-plastin, in combination with other signature genes, is elevated in the early stage tumor, then the tumor is a high risk for metastasis and should be treated with chemotherapy.

The above figure consists of a pair of two-dimensional protein profiles that show the difference in expression of L-plastin and its phosphorylated form (upward arrows) between a human fibrosarcoma (left panel) and a normal human fibroblast (right panel).

My colleagues and I also found that L-plastin elevation is likewise a good marker for other female reproductive tumors like ovarian carcinoma, uterine lieomyosarcoma and choriocarcinoma (uterine/placental tumor), as well as fibrosarcomas, melanomas, and colon carcinomas. Abundant induction of L-plastin synthesis was likewise observed following in vitro neoplastic transformation of normal human fibroblasts by the oncogenic simian virus, SV40 (see Table IV in Lin et al, 1993).

The abundant synthesis of L-plastin that we found normally in white blood cells (lymphocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, etc.) suggested to me that the presence of L-plastin in epithelial tumor cells like breast cancer cells contributes to the spread of these tumor cells through the circulatory system to allow metastasis at distant sites. Indeed, both plastin isoforms have now been linked to the spread of tumors by metastasis, an understanding that is summarized in another Pauling Blog article from 2014 and, more recently, in other studies.