It was one of the very few parties to which I’d been invited in Edinburgh. “When a Scotsman asks you where you’re from,” one of the guests said to me, “he means where you were born.” Although we have no control or say over where we come into the world, we do feel that the place has a claim on us. Combined with my undying interest in local history, that means I like to read books about my native Pennsylvania. I was a first generation Pennsylvanian, to be sure, but to keep a nearly forgotten Scotsman happy, that’s where I’m from. Sarah Hutchison Tassin’s Pennsylvania Ghost Towns: Uncovering the Hidden Past is that familiar kind of book considered light reading, geared largely to the tourist and nostalgic past visitor or homebody crowd. Still, these kinds of quick studies often inspire the imagination. Lots of people lived here before you did.

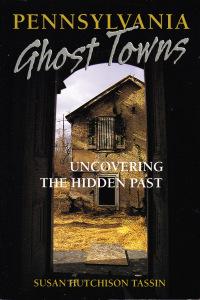

It was one of the very few parties to which I’d been invited in Edinburgh. “When a Scotsman asks you where you’re from,” one of the guests said to me, “he means where you were born.” Although we have no control or say over where we come into the world, we do feel that the place has a claim on us. Combined with my undying interest in local history, that means I like to read books about my native Pennsylvania. I was a first generation Pennsylvanian, to be sure, but to keep a nearly forgotten Scotsman happy, that’s where I’m from. Sarah Hutchison Tassin’s Pennsylvania Ghost Towns: Uncovering the Hidden Past is that familiar kind of book considered light reading, geared largely to the tourist and nostalgic past visitor or homebody crowd. Still, these kinds of quick studies often inspire the imagination. Lots of people lived here before you did.

A couple of factors stood out to me about Pennsylvania’s elder communities. One obvious feature is that a number of them began as intentional religious communities. Often breakaway sects from some major denomination, they established settlements to pursue spirituality in their own way, generally with strict rules, such as celibacy, that would spell their ultimate demise. Pennsylvania is well known for its separatist Anabaptist sects—Amish, Mennonites, and others who’ve been around for centuries and have integrated into the cultural mix of the state. I had no idea that a few ghost towns remain where some less successful spiritual seekers had broken ground. The second feature that stood out is how many communities were intentionally founded for commercial purposes. Often these were mining or lumber-processing towns. Some wealthy individual would buy a natural resource, build houses and a communal store, and permit workers to purchase goods only there. This meant individuals could never save money and never really afford to leave the mine or mill.

These are two very different conceptions of what it means to live in community. One is overly idealistic the other overly exploitative. At one end, the basic necessities of life—food, shelter, clothing—were kept from those who found themselves, like most of us, in need of a job. Or, at the other extreme, being held back from eternal life by failure to keep to the rules of a newly revealed religion. I never really thought of towns intentionally founded in these ways before. My naive view was more eclectic. But then, what do I know? I was born in a small Pennsylvania town and never thought to question why it was there. Where are you from? It’s a matter of perspective.