[Part 2 of 3]

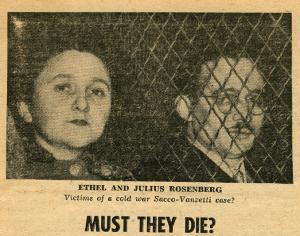

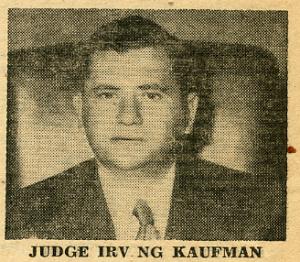

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg’s conspiracy trial, presided over by Judge Irving Kaufman, began on March 6, 1951. Representing the United States was attorney Irving Saypol, well-known for his recent successful prosecution of a government official accused of being a Soviet spy and convicted of perjuring himself before the House Un-American Activities Committee. After the Rosenbergs were ultimately convicted, Saypol was heralded by Time magazine as “the nation’s Number One legal hunter of top Communists.”

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg’s attorney, Emanuel (Manny) Bloch, was known for defending clients harboring left-wing or communist sympathies. However, the Rosenbergs were not the only defendants being placed on trial – Morton Sobell, who was represented by Harold Phillips, was also among the accused.

Sobell had been recruited by Julius Rosenberg in the summer of 1944 and was accused of stealing information while working as an engineer at General Electric. Sobell was advised by his attorney to say as little as possible throughout the trial in order to avoid implicating himself in the Rosenbergs’ activities, and indeed he never took the stand. Later outrage against the treatment of the Rosenbergs and their subsequent sentencing also included protestation of the judicial treatment of Sobell as well.

Although the trial was an item of intense media interest throughout its duration, the closing statements and summations of the case were especially interesting as they served as one final opportunity for the attorneys involved to provide their perspectives to the jury. Emanuel Bloch, the Rosenberg’s lawyer, focused on the Greenglasses as villains who had framed Ethel Rosenberg and broken family bonds by testifying against her. Bloch alleged that the Greenglasses had fooled the FBI and allowed Ruth Greenglass to get off scot free, while Ethel suffered for a crime that she did not commit.

In his summary argument, Bloch did not draw attention to the fact that the case against Ethel was far weaker than that made against Julius, as doing so would strengthen the validity of the conspiracy charge issued against the couple. Instead, Bloch’s primary tactic was to appeal to the emotions of the jurors.

The prosecution, on the other hand, argued that it was not the government’s fault that their key witnesses, the Greenglasses, did not have an unimpeachable reputation. In his statement, Irving Saypol, the government’s lead attorney, emphasized that the jury also had ample and damning material evidence on which to rely. He likewise reminded the jury that, although communism was not on trial, it was communism and a devotion to the Soviet Union which brought the Rosenbergs and Morton Sobell to commit the crime of which they were accused.

Heading into their deliberations, all twelve jurors were leaning towards convicting Julius, with one juror arguing against convicting Ethel. This remained a sticking point throughout discussions that night and into the next morning, but at 11:00 A.M. the group reached complete unanimity. On March 29, 1951, the jury delivered a guilty verdict against Ethel and Julius Rosenberg.

The sentencing that ensued also provided a unique look at how the trial was received in America. At the sentencing hearing held the next week, on April 5, both Bloch and Phillips did what they could to try and lessen the severity of the punishments being considered. Bloch in particular argued that the Rosenbergs did not wish to change the fate of the United States with their actions during World War II, nor did they even have the power to do so. Rather, they were aiding an ally of the United States at the time of the alleged crime. Bloch further argued that, had they been tried at the time of their alleged crimes – circa 1944 – the levels of tension and fear surrounding the US’s relationship with the Soviet Union would have been far lower, and the courts would have been much more likely to show leniency.

Bloch also read a statement from the Yale Law Journal which explained that the information given to the Soviets through the atom spies was not as crucial to the development of Soviet nuclear weapons as was commonly believed. The defense attorney concluded that it would be unfair to hand down death sentences to the Rosenbergs, as other notorious traitors including Iva Toguri D’Aquino – more commonly known as “Tokyo Rose” – and Mildred Gillars, aka “Axis Sally,” had received lesser sentences for their treasonous activities during the war. Many of these issues broached by Bloch at the sentencing hearing continue to be points of contention for scholars and commentators when they consider the Rosenberg trial today.

A statement issued by Judge Irving Kaufman prior to sentencing made it pretty clear that the court was not in a forgiving mood. In his remarks, Kaufman assigned partial blame for the onset of the Korean War to the Rosenbergs, as he believed that the information they leaked had led the Soviets to develop an atomic bomb sooner than expected, thus enabling Moscow to encourage Communist aggression in Korea. In the judge’s estimation, this rendered the Rosenbergs’ crime “worse than murder.”

Kaufman also emphasized the role that Ethel had played in the ordeal by encouraging and assisting her husband, thus making her a “full-fledged partner” in the espionage, and for this reason he believed that she should not be shown any mercy.

Without question, Judge Kaufman’s statement was imbued with the sentiments that attorney Bloch had feared would cloud the decisions made at the trial – namely, the crisis mentality that so often defined the Cold War era. As Kaufman put it

The issue of punishment in this case is presented in a unique framework of history. It is so difficult to make people realize that this country is engaged in a life or death struggle with a completely different system. This struggle is not only manifested externally between these two forces but this case indicates quite clearly that it also involved the employment by the enemy of secret as well as overt outspoken forces among our own people.

After reading his statement, Kaufman sentenced the Rosenbergs to death, while Morton Sobell was sentenced to 30 years in jail. The death sentence was to be carried out during the week of May 21, 1951, less than two months after the hearing had taken place. In this, the judge emphasized his desire to expedite the execution process, a continuing theme throughout the Rosenbergs’ later appeals.

Interestingly, the sentences issued by Judge Kaufman were not in accordance with Justice Department guidelines and went beyond what the government thought was advisable given the situation. Just as in the deliberations of the jury, the main sticking point was Ethel’s fate and the question of whether or not she should receive the death penalty alongside her husband. And although Kaufman recommended that Morton Sobell be forced to complete his full thirty-year sentence without parole, he was in fact released in 1969 after seventeen years and nine months in prison.

On April 6, the day after the Rosenbergs hearing, David Greenglass was sentenced to fifteen years in prison, a judgement that, according to Kaufman, was “neither a light sentence nor a heavy sentence, but just a sentence.” Though this was also the sentence that prosecution attorney Saypol had suggested, it ran counter to assumptions made by Greenglass and his lawyer, O. John Rogge, who understood there to be an informal agreement with the government, wherein Greenglass would get off lightly – no more than five years imprisonment – due to his cooperation. However, the death sentences handed down to Greenglass’ sister and brother-in-law rendered his own slap on the wrist an unlikely presumption. Greenglass would eventually be released in 1960 after spending nine and a half years in prison.

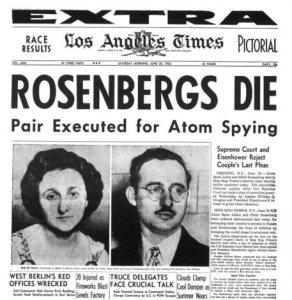

Despite Kaufman’s directive that the Rosenbergs be put to death promptly, the couple managed to appeal their verdicts over the next two years. However, their final appeal was thrown out on June 19, 1953, and the Rosenbergs were executed that day after a stay of execution was voided. Although their attorneys had asked that the executions be delayed until a later date due to the start of the Jewish Sabbath, their executions were actually moved up from the standard time of midnight in order to complete them before the Sabbath began. Their date of death happened also to coincide with their fourteenth wedding anniversary.

Today, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg remain the only Americans ever put to death in peacetime for espionage and the only two American civilians executed for espionage-related crimes committed during the Cold War.