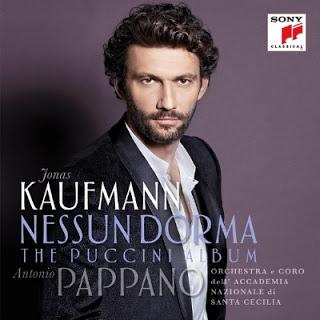

Does the world really need another Puccini album? Probably not. But opera-lovers as a group are very ready to cry, with Lear, "O reason not the need!" And Jonas Kaufmann, together with Antonio Pappano, has recorded a disc that is more than just another Puccini album. This is, in no small part, due to the luxury of having the very fine orchestra and chorus of the Accademia di Santa Cecilia on board with the project. Under Pappano's baton, the orchestral contributions to this album do much to set it apart. This is no mere window-dressing or accompaniment, no mere setting for the voice; this is drama and commentary at once, blood and bones and breath. Kaufmann's work is also very fine, and, in places, nothing less than hair-raising. Although the album includes several of the most famous staples of the dramatic tenor's repertoire, it is in the lesser-known pieces, and in some unexpected moments, that Kaufmann's artistry is most interesting, and most effective.

Does the world really need another Puccini album? Probably not. But opera-lovers as a group are very ready to cry, with Lear, "O reason not the need!" And Jonas Kaufmann, together with Antonio Pappano, has recorded a disc that is more than just another Puccini album. This is, in no small part, due to the luxury of having the very fine orchestra and chorus of the Accademia di Santa Cecilia on board with the project. Under Pappano's baton, the orchestral contributions to this album do much to set it apart. This is no mere window-dressing or accompaniment, no mere setting for the voice; this is drama and commentary at once, blood and bones and breath. Kaufmann's work is also very fine, and, in places, nothing less than hair-raising. Although the album includes several of the most famous staples of the dramatic tenor's repertoire, it is in the lesser-known pieces, and in some unexpected moments, that Kaufmann's artistry is most interesting, and most effective.I am not a devotee of Traditional Tenor Heroics. I am, as is well-documented on this blog, something of a Jonas Kaufmann enthusiast. These two facts, rather than presenting a paradox, are intimately related. When singing is merely beautiful, I tend to find it boring. Self-loathing and despair are much more interesting. Ditto lust-driven decision-making sung with a passion that makes it sound inevitable and almost right. And Kaufmann is an intelligent and adventurous singer, who prefers exploring the flaws of tenor "heroes" to glossing over them. While "Donna non vidi mai" leaves me fairly cold, the remaining excerpts of Manon Lescaut, in which Kaufmann is partnered by Kristine Opolais, are very exciting indeed. Infatuation at first sight is far less intriguing than the sparking, ardent, dysfunctional relationship between the lovers in the rest of the opera. The unusual luxury of having four selections from the opera, tracing most of its arc, is a pleasure, allowing Puccini's gift for drama to shine. Spitting out "Sciagurata!" or snarling "Io pur schiavo," Kaufmann's Des Grieux is a man whose self-knowledge does not confer strength. His "Ah! Non v'avvicinate / No, pazzo son..." is, unusually, a defiance rather than a plea, daring the assembly to look on what he has become. It is dark. It is bitter. It is great. It's the next track, though, Le Villi's "Torna ai felici di," to which I can't stop listening. For me, it's the standout of the disc, featuring gorgeous phrasing, sensitive use of vocal color, and a whole lot of anguish.

I don't find Puccini's show-stoppers to be terribly engaging out of context. There is no lazy musicianship here, though. Pappano and the orchestra do a beautiful job of setting the stage for Bohème, Tosca, and Butterfly, playing with subtlety (yes, subtlety!) and tenderness. Kaufmann, admirably, resists the temptation to turn "O soave fanciulla" into a declamation, making it instead an intimate, eager protestation. He also gives "Recondita armonia" with some lovely diminuendo on the last, long-held note. Pinkerton can cry me a river, and I still won't care. The most conflicted bandit in the west, however, is another story. I know La Fanciulla del West isn't an opera the world's audiences are clamoring to hear (though I'm very fond of it,) but I would welcome a temporary vogue for this work while Kaufmann is singing Johnson-Ramerrez this well. The 1-2 emotional punch of "Or son sei mesi" and "Ch'ella mi credi" are both just about ideally sung, here; the music is a superb fit for his voice right now, and for his expressive scope. We even get the miners included in the latter, which is nice. Kaufmann gives a suitably dreamy and seductive "Parigi! È la città dei desideri," from La Rondine. I was pleased to hear that he still has this much flexibility and lightness in his voice.

Excoriating bitterness is, however, once again the order of the day in "Hai ben ragione," an undervalued aria, in my opinion. My sister's comment, overhearing this, was "He sounds like he's in either physical or mental torment here." "Both!" I rejoined; "he is a dock-worker protesting the exploitative nature of capitalism." It's not the kind of subject audiences expect from a gutsy, show-stopping tenor aria; I love it, and Kaufmann gave it with appropriate intensity. To my surprise and delight, "Firenze è come un albero fiorito" gives us a delightful break for youthful joie de vivre, from Kaufmann, and practically-visible sun-flooded Florentine vistas from Pappano's orchestra, before finishing the album with the prince with a death wish. Can someone please stage a ruthlessly unsentimental, pagoda-less Turandot and stick Kaufmann in it? Please? He sings "Non piangere, Liù," with a heartbreakingly sincere intimacy. He begins sounding merely beaten and sorrowful, before warming up (and scaling back the voice to pianissimo) for a melting "Dolce mia fanciulla..." Pappano and the orchestra were also great here; every time I've listened to it, I've longed for it to lead directly into the Act I finale, horrible fascination, death, gongs, and all. Also, Kaufmann does not sing "Nessun dorma" as though it is a cock's crow of triumph, the most obnoxiously heroic of Traditional Tenor Heroics. No, this is "Nessun dorma" as close to a philosophical reflection as it can come, plausible as the thoughts of a man absolutely alone in a city full of sleepless anticipation. There is actual interiority here, a melting "splenderò," a "Vincerò!" that sounds like the longing for surrender. Even here, Kaufmann manages something unexpected. And that, for me, is what makes him such a compelling singer.