John Boorman: Memories of Queen and Country

By Alex Simon

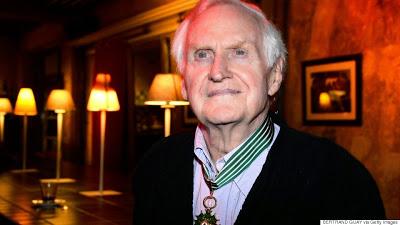

John Boorman first made his name as a filmmaker to be reckoned with upon the release of 1967’s Point Blank, one of the seminal films of that decade. Classics such as Deliverance (1972), Excalibur (1981) and The Emerald Forest (1985) followed, with 1987’s Hope and Glory, Boorman’s personal memoir of growing up in WW II London during the Blitz, being one of his career high points, garnering five Oscar nominations, including Best Picture, as well as winning a Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture (comedy) and sweeping that year’s BAFTAs in every major category.

2015 finds John Boorman, now 82, releasing what he says might be his swan song as a filmmaker, Queen and Country, the long-awaited sequel to Hope and Glory. The film finds Boorman’s alter ego Bill Rohan (Callum Turner) serving in the British army during the Korean War, but landlocked in the UK on a grim military base, presided over by a martinet sergeant-major (David Thewlis) and an indifferent commanding officer (Richard E. Grant). Only his bunkmate and best friend Percy (Caleb Landry Jones) can help Bill keep his sanity with their carefully orchestrated acts of rebellion. Bill also falls for a mysterious, aristocratic beauty (Tasmin Egerton) and must keep his libidinous older sister (Vanessa Kirby), who’s visiting from Canada, out of the clutches of eager men, including Percy. Queen and Country is a sweet and touching slice of nostalgic storytelling, a cinematic love letter to a bygone era and the universal experience of young adulthood, just on the cusp of trading childhood innocence for real-world cynicism. The BBC Worldwide North America release hits theaters in California and New York City February 27, then goes wider in March.

John Boorman sat down with Alex Simon to discuss his latest cinematic outing. Here’s what transpired:

Hope and Glory was one of my favorite films of the eighties. Queen and Country left me with the same feeling at the end: I wanted more. I think you should do a third chapter, about your entry into the British film industry in the 1950s.

John Boorman: Well, at the end of the picture there’s that final shot of the camera that stops, and that was a metaphor for the end of my career.

I heard rumblings that you might be retiring. Please don’t. We need you now more than ever.

(laughs) Well, thank you. We’ll see.

I imagine it’s difficult now more than ever to get the sort of films made that you make.

Yes, it much more difficult now to do daring things. I noticed particularly watching the Oscars, the foreign language category, there were these terrific movies: Timbuktu, Leviathan and Ida. By contrast, the American films that were up for Oscars, some of them were good, but they lacked the kind of daring that these other films had. I think there’s an element of fear generated by the studio—a fear of the audience. Any nuances or ambiguity have to be ironed out in case (the audience) doesn’t understand. On the one hand, it’s a fear of the audience and on the other, a fear of the corporate machine.

And the added factor of how will it translate to the Chinese and Indian markets.

Yeah, that also comes into it. It’s so different now.

Did you conceive of Queen and Country while you were writing Hope and Glory?

Yeah, when I finished Hope and Glory, I’d conceived of doing at least two more autobiographical films about my family. I wanted to do this one, about my national service and I wanted to do one about my grandfather. He had a pub, a gin palace really, in the Isle of Dogs, which was a very tough area in the East End of London. He had four daughters and when the German zeppelins were coming over and dropping bombs on the London docks, he built this bungalow on this island off the River Thames, which you saw in both Hope and Glory and Queen and Country. My mother and her three sisters spent their childhood away from World War I on that island. They grew up in the twenties and were flappers. It’s referred to in Hope and Glory, about the parties they had with Chinese lanterns. When we lost our house in World War II, my mother took us to the same place. So I wanted to do that story, but never got ‘round to it. I did make a film for the BBC, called I Dreamt I Woke Up, a one hour film. I was asked, along with several other directors, to make a film about their own environment. It’s partly a documentary in which I show people my home and all that, and when I want to deal with the spiritual or transcendent elements, I have this alter ego, played by John Hurt. Gradually my alter ego becomes more and more intrusive in my life. So doing autobiographical themes is something I enjoy. There’s also this character of a female journalist, and every bad thing that’s ever been said about me and my films comes out of her mouth. (laughs)

One thing I really appreciated about Queen and Country was that you kept the identical story structure and stylistics you established in Hope and Glory: an episodic structure with scenes that fade to black, with the first half taking place in a special world. In Hope and Glory it was London during the Blitz, and in Queen and Country, it’s national service on a cloistered army base. Then both films spent their second halves in the cottage on the Thames, your grandfather’s house, where there’s this tranquility and free-spiritedness in the air. I thought about it, and I wondered if you used that episodic structure because memory is episodic in nature.

Well yes, absolutely. The relationship between memory and imagination is very mysterious. If you tell a story about something in the past, you apply imagination to it. In Hope and Glory when I went back to the street where I was born, Rose Hill Ave., it was nothing like I remembered it. It was a very mean street, and I remembered it being rather idyllic and stretching all the way through London to St. Paul’s Cathedral. So I built the memory rather than the reality. In a way, making these films is kind of a betrayal to the memory, because now I remember the films and the memories themselves have gone.

Family affair: the Rohan family in Hope and Glory, above, and Queen and Country, below.

“When legend replaces truth, print the legend,” right?

(laughs) Yes, exactly. It’s almost impossible to say how much of both films are factual memories and how much is creative license. In both cases, when I started writing Hope and Glory, I just wrote down my most vivid memories, then I considered them and put them in order. I did the same thing with Queen and Country. Every incident in Queen and Country happened and all the characters were based on real people. For instance, the Ophelia character, although I did have this girlfriend who was aristocratic and at that time, a lower middle class boy like me was kidding himself if he thought he could have a relationship of any standing with someone outside his class. She wasn’t a handmaiden for the Queen, however. That part was creative license. (laughs)

I really liked Callum Turner, the young actor you cast as yourself. He was so natural, like you pulled him off the street.

I was always sort of sitting on the fence at that age, unlike the Percy character, who is very impulsive and just dives into things. Callum has a calm quality and, as you said, a great reality to him, an honesty. In every scene as I wrote it and as I shot it, I always asked myself ‘Is it true?’ Not ‘Is it real?’

Callum Turner as Bill Rohan.

Callum Turner as Bill Rohan. In an emotional sense, you mean?

Yes, always an emotional sense. In the purest way, I was able to be quite detached while I was shooting it. It was like it was about someone else. The only thing in Queen and Country I found very difficult emotionally to deal with was the scene when he sees his mother waving to someone across the river, and he realizes it was her lover from WW II, who you might remember as the character Mac in Hope and Glory. I was ten when that happened, and when I found out, I thought ‘Do I betray my father or betray my mother?’ That was a huge thing for me, and it’s a memory that still hurts.

There was one notable absence in this film: the character of your younger sister.

(laughs) Yes, my sister Angela, who’s two years younger than me. She’ll turn 80 in May. She said “Where was I?” I said, ‘Oh, you were away at boarding school.’ (laughs) I couldn’t fit her in.

I can understand that, especially considering the character of the older sister, Dawn, was so big and bright.

(laughs) Yes, there was that, as well. You know, two or three years ago I got a call from Montreal, from an agency, who asked if I was the brother of Wendy, my older sister. And they put this guy on the phone, who turned out to be her son. At the end of Hope and Glory, she has the baby and marries at 17, moves to Canada. During the year her husband was away in the army, she produces another child, out of wedlock, and gave it away. Then I found myself talking to him on the phone. I said ‘You’ve just missed her. She died two years before, but if you want to know what she was like, rent Hope and Glory.” Then when I did this film, I called him again and said, ‘If you want to know a bit more about your mother, you should see this film, as well.’ (laughs) So he came down to New York last week to see it. In the Q&A; afterward, I told the story and had him stand up.

It struck me while watching this film that Wendy, Dawn in the film, was twenty years ahead of her time: she would have been a perfect hippie in the sixties.

Absolutely. She was.

I saw the documentary your daughter Katrine made about you, Me and Me Dad, and thought it was terrific. You allowed yourself to be portrayed, warts and all.

Well, she wanted to do it, and I agreed. I don’t want anything to do with the editing or any approvals. That’s all up to you. I must admit, it made me cringe quite a bit. I only saw it once. (laughs) People seem to like it. It’s very emotional and deals particularly with my eldest daughter, Telsche, who died of ovarian cancer in 1997.

Your 1974 film Zardoz is currently being restored for Blu-ray release. I’m a huge fan of it and have probably seen it seven or eight times, but still don’t completely understand it.

You’re in good company, I think. (laughs)

I’ve always wanted to ask, were there just massive amounts of marijuana involved in the making of that film?

I get asked that constantly.

And do you ever answer?

Let’s talk about something else, shall we? (laughs)