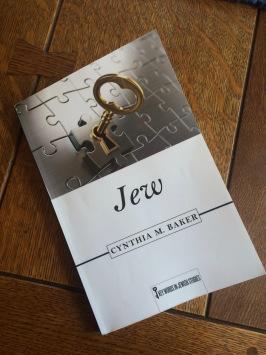

As someone who has been labeled a “first class disrupter,” I was of course immediately attracted to the chutzpah of a book entitled, simply, Jew. Published recently as part of the Rutgers University Press series “Key Words in Jewish Studies,” this slim volume by Cynthia M. Baker, a Religious Studies professor at Bates College, is dense with insight, nuance, and helpful frameworks for thinking about the complex histories and meanings of the word Jew, and more broadly, the complex histories and meanings of religion. Jew is not an easy read for the non-academic–I was grateful for my years living with semiotics majors in college, and my acquaintance with the ideas of Foucault and Derrida. But it is an essential read for anyone wrestling with contemporary Jewish ideas about identity, and that includes all of us in interfaith families with Jewish connections.

Faced as we are with an increase in public anti-Semitic, anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim and racist acts in the current political climate, Baker’s elegant analysis of the word Jew (she chooses to italicize it and I will do the same) feels especially timely. Baker traces the evolution of the word through Greek, Latin, Hebrew and Aramaic. She illuminates how the term Jew was central to the “historical creation of Christian identity and worldview.” She delineates how Jew is often synonymous with “the other,” and has only recently been reclaimed as a (“fraught”) self-referential term of pride. She deconstructs the false binary of Jewish-by-religion versus Jewish-by-ethnicity, embedded in colonial and patriarchal Christian theologies. And she tackles the subtle differentiation of Jew and Jewish

Baker writes of how the identity of Jew inhabits a space where “belonging and alienation, longing and being hover in a delicate–and sometimes indelicate–balance.” And she writes of the “dissolution of standard dichotomies–including us/them, homeland/diaspora, religious/secular, masculine/feminine, even Jew/Gentile…” This space, this balance, this dissolution, will feel profoundly familiar to those of us in interfaith families choosing interfaith education for ourselves and our children.

In her final chapter, entitled “New Jews: A View From the New World,” Baker cites Being Both: Embracing Two Religions in One Interfaith Family. I am grateful that she acknowledged the significance of the 25% of Jewish parents in interfaith marriages raising children with both family religions. However, she goes on to offset the (mainly positive) experiences documented through surveys of hundreds of parents and children in Being Both, with a single anecdote meant to convey the “often-painful challenges” of embodying multiple identities. For this counter-example, she chooses an individual who is transgender, and whose parents became Orthodox. It hardly seems fair to critique the idea of interfaith education for interfaith children while layering on the complexities of conversion, fundamentalist religious practice, and gender identity. Nevertheless, I am glad we are included in the shade of Baker’s very big tent for this book. And I hope she will return to a deeper investigation of multiple religious practice in interfaith families–of who we are, where we are going, and what it all means.

Journalist Susan Katz Miller is a speaker and consultant on interfaith education for interfaith families. Her book Being Both: Embracing Two Religions in One Interfaith Family is available from Beacon Press.

Advertisements