This is our first post talking about women in Afghanistan (because they are Brown girls too), but in a different light – health. While we do not have the writer’s base to be able to give the “real” Afghan woman’s voice, there are already great initiatives out there, such as the Afghan Women’s Writing Project.

This is our first post talking about women in Afghanistan (because they are Brown girls too), but in a different light – health. While we do not have the writer’s base to be able to give the “real” Afghan woman’s voice, there are already great initiatives out there, such as the Afghan Women’s Writing Project.

This particular post comes from a colleague of mine, Sera Bonds. Sera is a midwife, and a founder of nonprofit, Circle of Health International (COHI), in which she works directly with Afghan women. There certainly is a Westerner presence in Afghanistan, and not all of it is negative. There certainly are questionable “development people” there, but Sera’s ability to tell the ground realities of the situation of women’s health in Afghanistan speaks volumes to the basic fundamental of double standards. Sera has shown humility in putting local leadership at the forefront of the areas that COHI works in, which is why we are featuring her post here today. I personally am a public health post, so this excited me very much, so wanted to bring another change in direction for our posts today. Here is Sera’s post (and our first non-Desi one too) on midwifes in Afghanistan and the work of her organization, COHI.

Afghanistan is a country that brings to mind a complicated array of images: impossible mountain ranges, the deep blue of Lapis, red fields of poppy flowers, Russian tanks, the colors deep purple and orange, and bustling open air markets. All of these exist at the same time and in the same space as the occupying forces of yet another military, that of America’s, prepares to leave. They have seen too many people come and go.

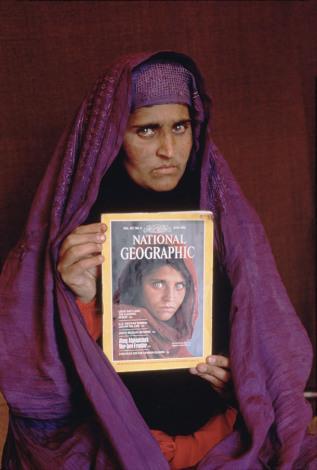

A well-known photograph graced the cover of National Geographic in 1985. You know her – she is the woman with the stunning eyes. Twenty years later, the photographer found her living in a refugee camp in Pakistan. Her life has not been an easy one, as told by Cathy Newman for National Geographic:

Time and hardship have erased her youth. Her skin looks like leather. The geometry of her jaw has softened. The eyes still glare; that has not softened. “She’s had a hard life,” said McCurry. “So many here share her story.” Consider the numbers. Twenty-three years of war, 1.5 million killed, 3.5 million refugees.: This is the story of Afghanistan in the past quarter century..

Now, consider this photograph of a young girl with sea green eyes. Her eyes challenge ours. Most of all, they disturb. We cannot turn away.” (See original article here)

Sharbat Gula has three living children, or did at the time of the most recent article in this famous publication. She has given birth to four, but one died in infancy. She was married at 13. This is one of the primary reasons that women in Afghanistan die at the rate they do when they become pregnant, they are too young to bare children.

Truthfully, the cause of death for pregnant women and new mothers in Afghanistan is something that is rooted in the deep patriarchy that Afghan women face. This level of patriarchy is appalling to even those of us who face some level of double standards in privileged spaces. It is poverty, and it is discrimination so severe that women are killed simply for being women. Being killed does not have to be deliberate or violent, by the way. It is as simple as women dying of anemia and obstructed labor. Of course, you may ask, how one not expect those causes in a place ravaged with war and poverty?

Well, there are resources, however limited they are, but the excuse for women not being treated in healthcare settings seems to come down to one thing: izzat. We have commonly heard izzat to mean honor, but in that honor is an overstretched notion of “modesty”. Izzat runs through the veins of the Pakhtunwali code (and while Pakhtuns are not the only ethnic make-up of Afghanistan, this code dominates the landscape we hear of today). Pakhtunwali is an unwritten code that guides the everyday aspects of respect that Pakhtuns (and many other cultures similarly relate to) pride themselves on. Yet, the code is taken literally to the point of denying access of such a basic health right. Where is the izzat in that?

Many Afghan women are denied access to education, much less the outside world. The arrival of their menstrual cycle, for example, means they face even further seclusion from men, and from all of society. Women live a life closed in their father’s home until they relocate to a life of seclusion in the home of their husband. Of course, if they are of a good “kismet” (fate), they will have a kind, maybe progressive husband and in-laws. Sadly, good kismet does not choose a lot of women, especially when it comes time for such a major event: the birth of a child. Many of these women after marriage will face difficulty in their pregnancies because they are not close to a major hospital or there are only male doctors in their areas. This is where midwives come in.

Midwives save lives. Many lives, especially in the parts of the world where the safety and health of mothers is an afterthought – if it is given a thought at all. Afghanistan – with all its natural beauty, rich culture and history – is one of these places, or so its maternal mortality rate demonstrates. In rural Afghanistan especially, purdah is strong. Therefore, when a woman who belongs to a poor and often illiterate family (literacy rates for women in Helmund province in the south are 1%) needs emergency or specialized care, and the only person there to provide it is a man, it is denied.

It is very possible that Sharbat’s pregnancies and deliveries were attended by midwives, as most births are outside of North America and other developed nations. We don’t know for sure, but I want to believe that for all of the suffering this woman has endured, and continues to endure, that when she was pregnant and laboring, a midwife was with her.

Midwives help women, regardless of class, race, and social standing. In the women who need us, call us, walk miles, days to get to us, we see ourselves. We see mothers, sisters, mothers, sometimes lovers, and we see strength. This is why Circle of Health International (COHI) works with midwives. Midwives are the doors through which peace, justice, and grace pass with each new life that arrives in their hands. With each birth there is the hope of greater peace, greater compassion, and a greater love of women.

Courtesy of Afghan Midwives Association Website.

COHI is working to support a trusted advocate and promoter of midwives in Afghanistan, the Afghan Midwives Association. Specifically, COHI is working to get supplies, funding, and training to the organization itself so that they can best determine what is needed on the ground to aid the midwives, and therein, the women of Afghanistan. Supporting midwives is what COHI does, and the Afghan midwives are our heroes. We are in awe of their courage. We are aspiring to increase their capacity to support pregnant women not because we believe that they don’t have capacity already, but because it is what they are asking for. We follow their lead, and do what we can to get them what they ask for.

Circle of Health International is known to provide women’s health services in war and disaster settings. They are US-based and are currently working in local partnerships in Afghanistan, Jordan, the West Bank, and Israel. They have also been involved in local partnerships with women’s organizations in Tibet, Sri Lanka, and Tanzania. The organization provides the services identified by the local organizations they work with, and if they can’t provide them, then they advocate on behalf of their partners to find the services they’ve requested. In the 8 years since this small organization was founded, they’ve served near 3 million women, and hope to continue to do this important work for many years to come.

Today (March 4, starting at 7 pm CST) and tomorrow all day, COHI is doing a special 24-hour fundraising effort. Do help them out. Click here to learn more: https://amplifyaustin.s3.amazonaws.com/npo80316.html