Always a surprise in that AHed story below the fold of The Wall Street Journal's front page

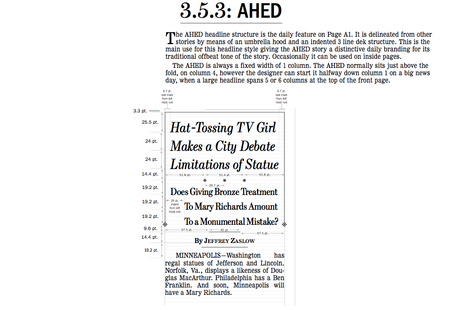

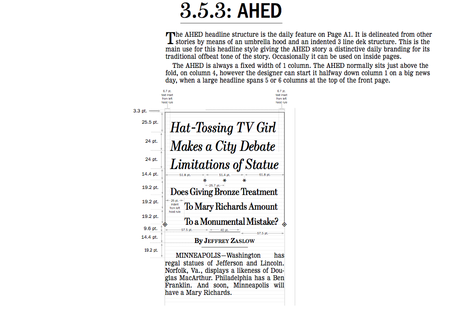

How The Wall Street Journal's styleguide describes the AHed, one of its most celebrated story structures

Greta Garbo is, without a doubt, the world's best known hermit wannabe: but, can any celebrity be a hermit today?

As soon as I found myself staring at a front page of The Wall Street Journal for Thursday, June 19, my eyes quickly scanned--and skipped---such headlines as "U.S. Signals Iraq's Malaki Should Go," and "House Staff Under Scrutiny As Trading Probe Heats Up", but was instantly attracted to the so called AHed story at the bottom of the page.

The AHed is one of the WSJ's best preserved traditions, dating back 80 years at least and always surprising readers of the venerable financial daily. When I was redesigning the WSJ, I was promptly told that the AHed was to be maintained in its place (usually under the fold of the page), with its distinct style (it is called AHed because it carries a sort of hood to package the headline), and,most importantly with the type of quirky stories that surprise, seduce and seldom have anything to do with the news of the day.

And so, on this edition, the AHed read: "Wanted: Hermit. Must be People Person."

Mind you, it is not that I am looking for a new position, let alone as a hermit, which is probably the last occupation on earth I would like to pursue.

What caught my attention is the fact that, in Switzerland, where the story is based, the town's hermitage is having trouble replacing the hermit who abandoned her job complaining that she could not lead the life of a hermit there, what with tourists stopping by, not to mention the intrusion of social media.

As the article states, the job of the hermit is not what it used to be. Tourists can now reach secluded spots of the world, while modern technology makes it harder to escape from friends and family via social media.

Even hermits connect to the Internet, who would know?

While the WSJ AHed story touches on a subject of hermits, which we rarely read much about, what I read here is that in today's digital age, the information comes to get us, and not necessarily the other way around.

Many of us are far from leading the life of a hermit, some of which take a vow of poverty, chastity and obedience. But we can all sympathize with those hermits who miss their solitude. Twice yesterday, while I was engaged in a social telephone conversation with a friend, I had pings on my phone distracting me and inviting me for a detour to a News Digest, and, later, to breaking news about the financial markets, not to mention two or three short messages on my iPhone screen about mails received and Facebook comments.

There are times when all of us want to be like that hermit in the Swiss Alpine city of Solothurn, or like the most famous of all hermits, Greta Garbo, the Swedish actress who made the phrase "I vant to be alone," her trademark.

Tough luck being left alone today, Greta, or anybody else.

It is the journalism of interruptions that interrupts us, the journalism of everywhereness that finds even the most reclusive of hermits.

The Swiss ad states: "Wanted: Hermit; Must Be a People Person".

For us storytellers the challenge, then, continues to be that of finding that story that seduces even the most disciplined and resolute of hermits.