While browsing at my local bookstore yesterday and looking for a diversionary read, I serendipitously discovered The Ordeal of the Longhouse: The Peoples of the Iroquois League in the Era of European Colonization (1992) by Daniel Richter. Although I’m only halfway through, it seems to be the book for those interested in a comprehensive history of the Iroquois.

The second chapter, which examines the origins of the Iroquois League, highlights the role of religion in group formation and cohesion. Although I have serious reservations about group level selection (and doubt that it exists), the Iroquois may be the closest thing to an historical example.

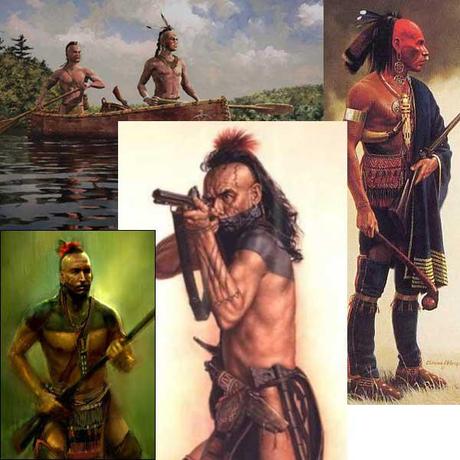

During the 1400s, the five tribes (Mohawk, Seneca, Onondoga, Oneida, and Cayugas) that eventually formed the Iroquois League were constantly at war with one another and their neighbors.

Map of Iroquois and Neighboring Tribes

Aside from all its other unpleasantness, the constant cycle of retributive war had devastating demographic effects on the tribes.

Though it is difficult to separate fact from subsequent hagiographic fiction, legend has it that Hiawatha lost several children in the warfare and wandered into the forest, grieving and inconsolable. Literally losing his mind, Hiawatha encountered a supernatural being named Deganawidah, The Great Peacemaker. Hiawatha was given rituals and a message that he carried to the five tribes, which heeded the words and formed “The Great League of Peace and Power.” Although this is often abbreviated to “Iroquois League,” the shortened form obscures the purpose of the confederation: peace between the five tribes and power or war against non-member outsiders.

While the Longhouse and wampum rituals are the most famous of those allegedly given to Hiawatha, perhaps the most important were the mourning and condolence rituals which surrounded warfare and slave-taking. Richter explains:

The connection between war and mourning rested on beliefs about the spiritual power that animated all things. Because an individual’s death diminished the collective power of a lineage, clan, and village, Iroquois families conducted “Requickening” ceremonies in which the deceased’s name, and with it the social role and duties it represented, was transferred to a successor.

Such rites filled vacant positions in lineages and villages both literally and symbolically: they assured survivors that the social function and spiritual potency embodied in the departed’s name had not disappeared and that the community would endure. In Requickenings, people of high status were usually replaced from within the lineage, clan, or village, but at some point lower in the social scale an external source of surrogates inevitably became necessary.

The “external source of surrogates” were nearly always war captives. Such captives were inspected, tested, and either adopted into the tribe or ritualistically killed and actually eaten. In the case of adoption, the physical power of the prisoner was appropriated. In the case of eating, the spiritual power was appropriated (giving “food for spiritual thought” an unsettling meaning).

By all accounts, the Iroquois League was powerful and feared. Although it changed considerably over the centuries through its interactions with European powers and colonizers, its success and durability says something important about the power of shared beliefs.