Irène Jacob Cuts Deep

By Alex Simon

French-Swiss actress Irène Jacob cemented her status as one of her generation’s greatest talents through her work with legendary Polish director Krzysztof Kieślowski: The Double Life of Veronique (1991, for which she was awarded Best Actress at Cannes) and the final chapter of his Three Colors Trilogy, Red (1994).

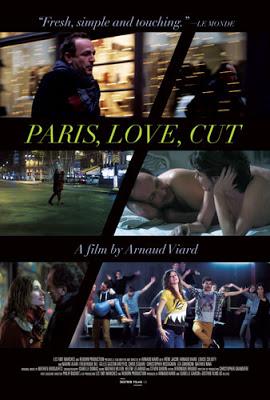

Jacob comes from an accomplished family: her father Maurice was a renowned French physicist, her mother a successful psychotherapist, and her three brothers are composed of two scientists and a musician. After making her film debut in Louis Malle’s Au Revoir Les Enfants in 1987, Jacob has literally not stopped working. Her latest film, written and directed by her co-star Arnaud Viard, is Paris Love Cut, Viard’s semi-autobiographical tale of a filmmaker trying to balance his personal life, career and sanity in an increasingly shifting landscape. Jacob is delightful as Viard’s very patient (and very pregnant) fiancée. A charming seriocomedy reminiscent of Woody Allen, Paris Love Cut makes its U.S. debut December 6 on iTunes, Amazon, Google Play & Vudu from Distrib Films US.

Irène Jacob spoke to The Hollywood Interview by phone recently. Here’s what transpired:

I enjoyed Paris Love Cut. I wasn’t familiar with Arnaud Viard prior to seeing it, but I kept feeling I was watching a Woody Allen film, in French.

Irène Jacob: Yes, like Woody Allen he is also the writer/director and his work is very personal. He has a tenderness but also a sense of humor. It’s true.

Did you find yourself relating to the story in terms of how difficult the film business is?

Yes. Arnaud’s first film, Clara et Moi, I liked very much. I felt I could trust him, and he brought an honesty to his work, including how difficult the business is. His first film was very well-received, for example, but he still had a hard time getting Paris Love Cut financed.

That also reminded me of Woody Allen: a love-hate view of show business.

(laughs) Well, how can any sane person not feel that way?

What is it you look for when you choose a part? I know you’ve always been very particular in the parts you do choose.

I’d say it’s a combination of things. Am I touched by the project, let’s say. Also, how much time it will take for me to participate in the film. Also, does the director know how to film people with humanity and tenderness?

You come from a remarkable family. Your father was a famous physicist.

Yes, he worked on the Big Bang, quantum physics. My mother was a psychologist. Two of my brothers are scientists; one of them is at Harvard working on global warming. He was saying to me the other day, “People believe in doctors, but they don’t believe in scientists, which makes no sense. The same people who will take the word of their doctor won’t take the word of a scientist that global warming is real.”

Don’t get me started on that, or the fact that we’ve just elected an administration who are scientific deniers. Since we’re on that subject, what’s the reaction been like in Europe regarding Donald Trump’s election?

We are very worried. In France we have an election coming up, too and want to make sure that our own freedoms aren’t affected.

I know that xenophobia is also sweeping Europe, particularly after the terrorist attacks in Paris.

Yes, it’s a global issue and we need people to trust again. We can love one another, we can open our doors, we can try to work together while still accepting our differences.

I also think during tough times, great art can be produced.

Yes, in dark times, bright things need to be created and there needs to be a resistance.

I read a recent interview with Paul Schrader, whom you’ve worked with, and he said “It’s time for films to get angry again.”

I admire Paul Schrader very much, and he speaks very well. I understand his comment, but it’s also true that films should enlighten and bring us together.

I understand the same thing made us both fall in love with film, namely the work of Charlie Chaplin.

It’s funny, since we were just talking about resistance, I thought of Chaplin. I am so in awe that he would make The Great Dictator on the eve of the Second World War. How could he be so funny, so poetic and so grotesque at the same time? It’s such a masterpiece for me. I kept watching it with my kids today, and said “Can you imagine in the middle of a war, making a film that’s so full of love, but also has the courage to denounce something he knew was evil, even though a lot of people weren’t aware of it yet.” He remains one of my great heroes.

In Louis Malle's Au Revoir Les Enfants, her film debut, 1987.

You made an auspicious debut in Au Revoir Les Enfants, directed by another of my heroes, Louis Malle.

It’s funny, two weeks ago I met the little boy from the film, just by chance. He’s now in his late thirties. When I got the part, I watched many films from Louis Malle. He always went up against taboos: depression, adultery, collaboration, child prostitution, incest. He always took big risks. When he did Goodbye Children, he said “Of all the films I’ve made, I think they were in preparation to make this one.” So it was a remarkable experience, especially being my first film. I think it was very emotional for him, very important that make it, and make it properly.

Which brings us to Krzysztof Kieślowski. I re-viewed your two films with him, Double Life of Veronique and Red, this week and what struck me was what a painterly filmmaker he was.

The Polish tradition in working with the DP is very different from other countries, because the DP has a great deal of input and influence. He was asking the DP to come up with his own interpretation of the film, so he could focus on the actors. For example, in Double Life of Veronique, they had endless discussions in how it would be filmed, the color of the light, hand-held, putting the camera on a string and throwing it above the concert hall. It was fascinating to watch them collaborate.

What was Kieślowski like to work with for an actor?

He started as a documentary filmmaker, but then realized what he really wanted to film was the intimacy of people. I think he viewed his camera as a microscope and always wanted his actors to feel a kind of tension, as if they are dealing with and risking a lot. He would observe everything during rehearsal and have you use the most minute detail when he filmed. He never used a monitor, which really surprised Jean-Louis Trintignant, because Krzysztof was always kneeling just out of frame under the camera, watching us so closely.

As if you were under a microscope.

Exactly, yes!

What was Trintignant like?

He’s so clever as an actor. He will always do the most unexpected interpretation of a scene. For example, he’ll say “no,” but with a smile. Whatever he does is always surprising and provoking. It’s so inspiring when I watch him act. It’s always an open proposition he’s offering.

That’s his magic: in his eyes, he always looks like he has a secret.

Yes, he thinks more than he does.

Not long after Red, you got to work with another of the greats, Michelangelo Antonioni, in Beyond the Clouds.

He had a completely different way of working, because when I had met him, he’d just had a stroke, was confined to a wheelchair and had trouble speaking. But he still had written the script, was determined to make the film and Wim Wenders was there to help him organize the shoot and the shots. Whereas Krzysztof loved editing most of all and would shoot a lot that wouldn’t necessarily go in the film, Antonioni would only shoot what he knew he would edit. He would never discuss the shots with the DP. He was really more like a painter and was always like the main character in his own stories, with a singular point-of-view. He always wanted to design the shot on the spot. As I said, he couldn’t say much, but the one word he said constantly was “Bello,” it was his go-to word for everything. I’d say “I really loved your film L’Avventura,” and he’d reply, very serious: “Bello.” We’d do a take, then look to him for a response: “Bello.” (laughs) It wasn’t said in an artistic way, it was said as though he was really into something, like he was viewing a beautiful painting.

You just finished work on your first American TV series, Showtime’s The Affair. How has that been?

Doing a series is a new experience for me, a different way of working, but the people you work with are what makes it good, or challenging. I like how the story changes points-of-view and my character has one really interesting episode that’s from her POV. My part was actually inspired by a friend of the showrunner who’s a professor of medieval literature. I also prepared for my part by watching a lot of Éric Rohmer’s films, because stylistically, the show feels like it’s been very influenced by his work. The action is often very much in the dialog.

Any final thoughts?

Well, I think we’re going to be living in a very strange time very soon. I hope that we can all learn to live and work together openly, and will continue to keep the positive energy going.

Paris, Love, Cut - Official Trailer from Distrib Films US on Vimeo.