“Men and societies frequently treat the institutions and assumptions by which they live as absolute, self-evident, and given. They may treat them as such without question, or they may endeavour to fortify them by some kind of proof. In fact, human ideas and social forms are neither static nor given.” — Ernest Gellner, Plough, Sword and Book: The Structure of Human History (1987)

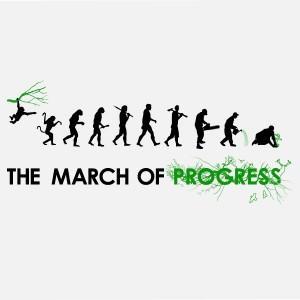

What constitutes “progress” and how can we measure or assess it? As regular readers know, this is a question that has been much on my mind over the past few years. During these years, I have often argued that biological evolution is not progressive and that cultural evolutionary models are inherently progressive because they normatively assume that complexity is adaptive advance. I have argued against “progress” in both these contexts, and in the process have observed that non-progressive evolution (whether biological, cultural, or both) entails the idea that religions, however they evolved or developed over time, are not progressive. In other words, “modern” religions are no more advanced, complex, or progressive than “primitive” religions.

This has been a big, and in some cases bitter, pill to swallow. There is a great deal of secular and religious resistance to the idea that evolution (and, by human-specific extension, history) is not progressive. I have encountered this resistance in the classroom, among friends, and my posts on these subjects have engendered a great deal of push-back. In light of all this, let’s take a closer critical look at the concept of progress. Let me start by saying this is not a definitive statement but is simply a sketch or initial consideration of the issues.

Because the concept of progress is so deeply bound up with our most cherished assumptions, wishes, and desires, our first and hardest task will be to avoid subjective and normative arguments about whether some allegedly progressive thing, development, or process is “good/bad” or “better/worse.” These kinds of arguments will not take us very far, are usually tautological, and will almost always devolve into context and culture specific disputes that evade principled resolution. With this in mind, let’s look first at some potentially neutral measures of progress. In the next post, we will evaluate anthropocentric measures of progress, and in a final post we will apply these to specific fields such as science, technology, politics, economy, philosophy, and of course religion.

Time: This measure is perhaps the biggest conceptual culprit when it comes to the idea, taken for granted by most, that progress is “natural” and “universal.” In western cultures, time is conceived in linear fashion, as having a beginning and end. This conception can be either scientific (starting with the Big Bang and concluding with the eventual collapse of the Universe) or religious (beginning with Creation and concluding with eternal Paradise). In both conceptions, the passage of time from beginning towards an eventual end is assumed to be progressive. While this may seem a natural way of thinking, there is nothing inherently progressive about the elapse, or apparent flow, of time. Time can occur, or be experienced, without the attendant value of progress. There is no reason, at least in principle, why an embodied observer of time could not conceive it dually: as progressive for the growth portion of a lifespan and as regressive for the decay portion of a lifespan.

While I am not aware of any such cultural conceptions, I do know that not all cultures conceive of time in linear fashion. Many aboriginal or indigenous societies are famous for conceiving time as non-linear and non-progressive. While it may be tempting to dismiss these cyclic conceptions of time as “primitive” flights of fancy, and to assert that we “moderns” know better, this would be a mistake. The notion of Eternal Return is a venerable one that can be found in many traditions, including modern philosophy and physics. Metaphysics and cosmology aside, it is also worth noting that cyclical conceptions of time may pragmatically reflect, or refract, millenia long experiences with exhaustible resources and fragile environments. They are, in this sense, inherently conservative rather than progressive.

Movement: This potential measure might also be called change. Movement can be forward, backward, sideways, angular, or circular. Neither movement nor change has an inherent direction. Putting it normatively, change can be for better or worse. There is nothing about this potential measure which suggests or requires progress.

Growth: Along with time, growth is a major conceptual culprit when it comes to the assumption of progress. If something is growing, we chart or measure the growth as “progress.” This is true, ironically, even of things like cancer. When the economy grows, we count it good. When crops grow, we count it good. But does growth necessarily imply progress? Surely not. For organisms, there is a period of growth, followed by decay and death. This only partly progressive. Volcanoes grow, but we don’t characterize this as progress. Societies grow, and while economists and other enthusiasts may applaud this, there are serious normative questions about whether rapidly increasing world population (watch this counter for five minutes and marvel) constitutes progress. We will leave these questions for later. Suffice it to say that growth is not an inherently progressive measure, though it certainly can be an ideological measure.

Size: This metric has much in common with growth, though there are some differences. Humans are impressed by size, perhaps because we are large mammals and only see things from the perspective of large organisms. This of course ignores the fact that we live in a world made and dominated by microbes. When paleontologists discuss the Big Five extinction events and say things like “the end Permian event resulted in extinction of 96% of all species,” they are referring to multicellular organisms. Microbes survived all those events quite well and microbes will survive all future extinction events. As Carl Woese likes to remind us, all multicellular organisms could become extinct tomorrow, and microbes would continue living on earth as they have for billions of years. But if all microbes became extinct tomorrow, all multicellular organisms would follow them in short order. Size, in other words, isn’t everything and it is surely not progressive. This aside and normatively speaking, we can all acknowledge that big tumors and large wars are in no way better than little ones.

Accretion: Although this potential measure is closely related to growth and size, I have chosen to treat it separately because there are some (such as the sociologist Robert Bellah) who claim that culture is cumulative and that “nothing is ever lost.” On a purely physical level, we know this cannot be correct: energy and matter are finite, and neither can accumulate beyond finite bounds. Such a conception also ignores entropy, which beyond its thermodynamic aspects surely plays an analogical role in human history and culture. Bellah, a Christian with a linear and teleological view of evolutionary history, seems to have been overawed and blinded by the cumulative impact of writing and expansion of symbolic storage facilities. This caused him to claim that culture, writ large on a world scale, was cumulative and that “nothing is ever lost.”

This is an incredibly naive claim, for cultural creation always involves some level of cultural destruction and social forgetting. Setting aside for the moment issues of globalization, industrialization, and homogeneity, it does not take much to realize that entire ways of life, being, experiencing, conceiving, and speaking have all been lost. We have only the faintest idea what human lives and societies were like during the Pleistocene. We have a better sense for what has been lost, and what we are rapidly continuing to lose, over the past few hundred years. In When Languages Die: The Extinction of the World’s Languages and the Erosion of Human Knowledge (2007), K. David Harrison gives us this sense and it’s all about loss.

Energy: This potential measure is non-directional and contains no inherent value as either progressive or regressive. It’s certainly not static. Humans are of course much impressed by energy and our attempts to create and harness it take us deep into anthropocentric considerations of progress. Let’s leave those aside for this post and simply consider energy in its cosmological and terrestrial forms. There is lots of energy out there in space, but I’m not sure anyone would claim that the ongoing process of galaxy, star, and planet formation and destruction is progressive. It is a process to be sure, but normatively characterizing it as progressive is an anthropic principle, something that exists only in the eyes of human beholders. Here on earth, energy manifests in its most raw and powerful forms as solar radiation (which creates weather) and vulcanism. A sometimes placid but often turbulent planet is neither progressive nor non-progressive. It just is.

Complexity: I have saved this metric for last because it’s a big one when it comes to progress. Like size and related to it, humans are suckers for complexity. On an organismic level, we see the world through the eyes of large mammals. In doing so, we tend to ignore the fact that our world is not just microbial to its core, but is also dominated (in terms of diversity and biomass) by less complex organisms such as plants and insects. On a societal level, we normatively assume that bigger, and hence more complex, is better. In doing so, we ignore the possibility that the specialization (and stratification) which is the engine of complex societies often results in a phenomenological and existential narrowing of human life at the level of individuals who constitute the masses. We also tend to forget that with 7.5 billion people on earth, the majority are masses. Of all the measures I have considered thus far, complexity is the most normatively fraught, stemming as it does from anthropocentric views and biases about the world. For this reason, I will consider it in more detail in the next post. Suffice it to say that there is nothing about complexity, per se or in and of itself, which suggests progress. Complexity must be evaluated on a case by case and contextual basis, with the context being something more than a single organism or type of society.

Stay tuned for Interrogating Progress Parts 2 and 3.

Research and Reading Note — As I began working on this post yesterday, I wrote the following: “We are sorely in a need of a book on the concept of progress, one that considers the ways in which the idea has developed and been deployed historically, philosophically, and cross-culturally. The standard narrative — i.e., that ‘progress’ is a child of Judeo-Christianity which was secularized by the Enlightenment and turned into a modern faith — is hardly sufficient. Deep-seated assumptions and taken for granted ideas about progress have a history and I’m sure that history will be revealing. If anyone is aware of such a book, please let us know.”

After writing this, I did some digging and found that there are in fact such books, all of which I have just ordered. Because I have not read these, my musings above may turn out to be naive or off the mark. We’ll see. But in the meantime, here are the books:

- History of the Idea of Progress (1980) by Robert Nisbet

- The Idea of Progress: An Inquiry into its Origin and Growth (1920) by J.B. Bury (free download here)

- A Short History of Progress (2005) by Ronald Wright