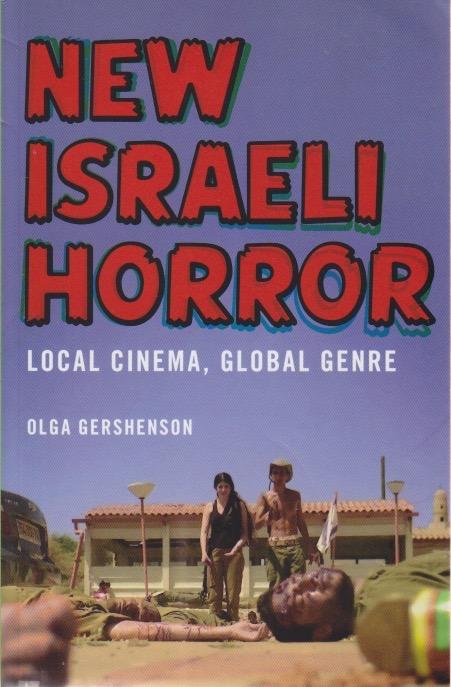

As someone who has written a couple pieces on Jewish horror for Horror Homeroom, I have developed a natural interest in international horror. I was one of those who scrambled hard to find The Golem (2018) when it came out, but was able to see it only in 2020. When I learned about New Israeli Horror, by Olga Gershenson, I knew I had to read it. The subtitle, Local Cinema, Global Genre, pretty much captures how she approaches the subject. It also helped me understand a bit better the way filmmaking works. I once, rather naively, asked a film scholar how many movies had been made. He responded, “It’s impossible to know.” Even experts in cinema can’t see every movie, and those of us who watch horror can’t see every horror film. (I wouldn’t want to.) I hadn’t realized, however, until reading this book, that in places like Israel it often comes down to state funding.

I’ve written quite a lot about Euro-horror over the past few years. Often cooperative ventures, these are horror films that aren’t part of the Hollywood system, and they are frequently quite good. Those of us who enjoy movies may not often think of who pays for them. It’s kind of like book publishing—someone’s got to pay for all this, and hopes to make their money back in the process. In Israel many movies are funded by official agencies. And such agencies tend not to like horror. New Israeli horror, by Gershenson’s reckoning, began only about 2010. One of the reasons I’ve turned to writing about horror is that its history isn’t so long as, say, ancient West Asian studies, which reaches back thousands of years. Reading about something not even two decades old, but still history, is fun.

I learned a tremendous amount from this book. Of the films discussed I’ve only seen one, the aforementioned Golem. Before writing Holy Horror, I paid no attention to where films were produced. I’d seen some international movies, sometimes obvious because of subtitles, but my usual fare is homegrown. I gather that I’ve been missing a lot by not seeing more Israeli horror. When you add Jewish horror (Jewish-themed horror, in my way of seeing things) to the mix, there’s a new angle to take on religion and horror. Many of the films Gershenson reads are about Israel’s army and critique of the militarism that has become part of life in Israel. I confess to not keeping up on politics because to me it tends to be scarier than horror. But I can see, from this book, that I’ve been missing some interesting cinema.