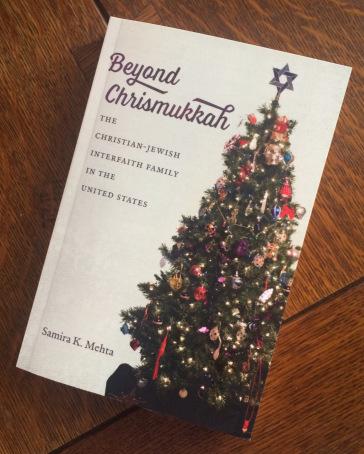

Just before my son's interfaith Coming of Age and Bar Mitzvah, I got a request from a graduate student who wanted to attend the ceremony as part of her ethnographic field work. My first reaction was, "no way." As a journalist and a control freak, I am wary of being the subject. And I wanted to stay focused on this intimate family celebration, and not have to worry about being misunderstood. But in the end, I relented. The desire to educate won out over the desire to control my family's narrative. And so, eight years later, Samira Mehta describes that ceremony in her new book, Beyond Chrismukkah: The Christian-Jewish Interfaith Family in the United States.

It is satisfying to feel seen and heard, as academics begin to acknowledge the rich complexity of interfaith families inside and outside of traditional religious communities. Mehta, now an Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at Albright College, provides an important historical framework for analyzing the choices made by interfaith families, from the 1960s to the present. (It's a great complement to Erika Seamon's Interfaith Marriage in America: The Transformation of Religion and Christianity). And she creates the most thorough and insightful academic analysis, so far, of those of us choosing to celebrate more than one family religion and culture. This is a book that all interfaith families, and those who love us, and those who study us, will need to read.

Samira Mehta and I have been in an extended professional conversation on these topics ever since that Bar Mitzvah, eight years ago. So this is not a standard book review, but rather an essay in response to Beyond Chrismukkah. Perhaps more objectively, Publishers Weekly called Mehta's analysis "thorough and impressive." They did quibble about a dearth of stories from actual interfaith couples. But here, I want to quibble with that quibble. Plenty of books (including my own) have told stories of interfaith couples. This book is valuable primarily for providing historical context and academic analysis, shedding new light on the family stories told in previous books.

The opening chapter of the book traces Jewish, Protestant, and Catholic institutional responses to interfaith marriage from the 1960s through the 1980s, decades when those institutions often worked to try to prevent interfaith marriage. (Both the rabbi who refused to marry my parents, and the rabbi who did marry them, are mentioned as playing key roles in this history). Also, Mehta's close analysis of interfaith families in popular culture through the 20 th century-in television, theater, films and children's literature-illuminates when and why and how these families struggled for acceptance in our culture.

Beyond Chrismukkah does include several detailed stories of individual interfaith families. So, in a chapter on how race and ethnicity intersect with religion in interfaith families raising Jewish children, Mehta portrays two interfaith families-one with a black parent, one with a Latino parent. And then she makes the keen observation that the Jewish community more readily accepts incorporation of Christian elements in interfaith family practice when the Christian partner is a person of color (and thus seen as having an important minority culture of their own), as opposed to a Christian partner seen as a member of the dominant white culture.

Four additional detailed family stories illustrate four different ways that interfaith families are resisting the expectation to choose one religious affiliation, and raising children "partially Jewish," (this is the Jewish survey terminology, not mine or Mehta's). Mehta did extensive interviews with a family that is unaffiliated but incorporates home-based Jewish and Christian traditions, a family affiliated as Unitarian-Universalist but incorporates Judaism in that practice, a family that has separate dual affiliations in both a Jewish and in a Mormon community, and a family (my family!) that affiliates with an intentional interfaith community providing Jewish and Christian education to interfaith children. "Rather than finding such families unmoored from religious practice and moral formation," writes Mehta, she found they "often developed a cohesive family narrative or sense of why they were together as a family beyond denominational constraints."

As Mehta points out, (and as I have pointed out), much of the research on interfaith families has been funded by Jewish institutions, and thus has not been objective. In contrast, Mehta, as a scholar, "starts from an assumption that the religious lives and realities of the interfaith families themselves are as important as the official policies of their religious organizations toward such families." This is indeed refreshing. And yet, this book still skews Jewish. Mehta includes two full chapters devoted to interfaith families raising children "only" Jewish, and hardly mentions interfaith families raising children Christian. At least in North America, Jewish institutional fears have largely driven the interfaith families narrative, and Mehta's work still reflects that reality.

Nevertheless, the arrival of Beyond Chrismukkah signals that more objective academic exploration of interfaith families and complex religious identities has finally begun. Alongside a handful of new books studying " multiple religious practice," (including Duane Bidwell's upcoming book), Mehta's work marks a new willingness to listen to the voices of those with complex religious lives. For, as she concludes, without grappling with "the many ways that those families live out their lives and with the hybrid identities that they create, it is no longer possible to understand religion in American."

Susan Katz Miller is the author of Being Both: Embracing Two Religions in One Interfaith Family.