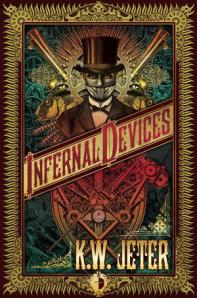

The first steampunk novel I read, although some would dispute the classification, was Neal Stephenson’s The Diamond Age. To be sure, I’d noticed other Victorian-style science fiction, but the idea of prescient technology settled into my head to nest for a while. I read a few other exemplars of the genre, finding each interesting in its own right. Having just finished K. W. Jeter’s Infernal Devices, however, I get a sense that I’ve neared the fount. Jeter is generally credited with coming up with the neologism “steampunk,” and this novel, while not his first, is fascinating for the heavy religious symbolism that is used throughout. In our secular, post-Christian age, we tend to forget that in the nineteenth century (actual, if not alternate reality) religion still played a tremendous role in people’s lives and outlooks. Infernal Devices uses that outlook quite effectively. The remnants of Cromwell’s puritan cause appear as the Godly Army, set against science and technology in a society still imbued with religious belief. When a flying machine appears overhead, the Scots suppose it is the beast of Revelation harbinger of the world’s end.

The first steampunk novel I read, although some would dispute the classification, was Neal Stephenson’s The Diamond Age. To be sure, I’d noticed other Victorian-style science fiction, but the idea of prescient technology settled into my head to nest for a while. I read a few other exemplars of the genre, finding each interesting in its own right. Having just finished K. W. Jeter’s Infernal Devices, however, I get a sense that I’ve neared the fount. Jeter is generally credited with coming up with the neologism “steampunk,” and this novel, while not his first, is fascinating for the heavy religious symbolism that is used throughout. In our secular, post-Christian age, we tend to forget that in the nineteenth century (actual, if not alternate reality) religion still played a tremendous role in people’s lives and outlooks. Infernal Devices uses that outlook quite effectively. The remnants of Cromwell’s puritan cause appear as the Godly Army, set against science and technology in a society still imbued with religious belief. When a flying machine appears overhead, the Scots suppose it is the beast of Revelation harbinger of the world’s end.

Like most steampunk offerings, Jeter offers us plenty of mechanical wonders. The hapless Mr. Dower, our protagonist and narrator, is the son of a mechanical genius, now deceased. The story involves Dower trying to unravel the many strands his father wove in a lifetime of invention and innovation. The one device that stood out to me, however, was the automaton priest and choir of Saint Mary Alderhythe, Bankside. Dower’s father had invented a robotic priest to go through the mechanical motions of an Anglican mass. Having sat through hundreds of such masses, I could see the point he was making. There are variables, but the overall draw of ritual is, well, its ritualism. The sameness that assures an assuaged deity and a safe congregation. The Godly Army, however, is more revisionist in intention.

Jeter, I’m sure, did not intend for the novel to be read for religious truths. It is rollicking and fun, with characters that you can’t believe but you want to. The driving force, however, behind much of the story is the religious bias of elements of London society. Dower, blamed for vices he doesn’t really have, is chased from his home by the Lady’s Union for the Suppression of Carnal Vice. The Godly Army, however, steals the show. Perhaps the most profound observation comes from Scape, who quips “That’s what you get.. when you give people Bibles and guns,” about the Godly Army. “It just messes up their brains.” At this point I began to wonder whether the story were really fiction after all. In this case the truth indeed perhaps lies in steampunk’s alternate history.