On September 20, 2021 Gary Gardner breathed his last. You probably have never heard of Gary. But twenty years ago, he was featured by 60 Minutes and People magazine. Gardner also figured prominently in my book Taking out the Trash in Tulia, Texas and in Nate Blakeslee’s Tulia.

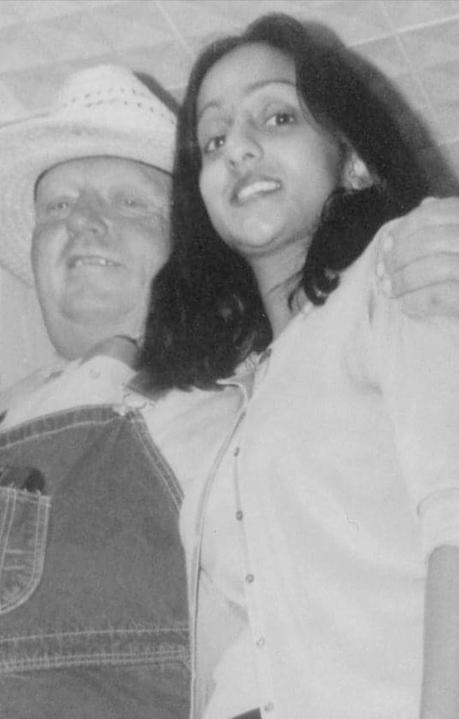

At nearly 400 pounds, Gardner had to turn sideways to get through our front door in Tulia, Texas. The first time I met him was on New Year’s Eve, 2000. He was wearing his trademark denim overalls and had a Mickey Mouse watch tied to the brim of his beat-up straw hat. “I’m dyslexic,” he explained, as he followed my gaze, “so the only way I can tell the time is by lookin’ in the mirror.”

Short days before, Joe (Bootie-Wootie) Moore had been sentenced to 90 years behind bars. The alleged crime was selling powder cocaine to undercover agent, Tom Coleman. Joe had worked as a seasonal day-laborer on Gary’s farm back in the day, but Gary had a deeper reason for taking an interest.

It all began four years earlier when the school superintendent introduced a high school drug testing plan. If you wanted to participate in athletics, you had to get tested. No exceptions. Gary sued the school board, arguing that, by the board’s own admission, Tulia had a lower rate of drug abuse than the state average.

So, when the Amarillo evening news announced that 46 “drug kingpins” had been arrested in Tulia (a town of 5,000, midway between Amarillo and Lubbock), Gary smelled a rat. In his mind, the superintendent and the sheriff brought Tom Coleman to town to prove the community had an out-of-control drug program. And poor Joe Moore and friends were paying the price.

Gardner was also driven by grief. During his dust-up with the school board, he and his wife Darlene had watched helplessly as their beloved son, Charlie, succumbed to brain cancer. When it was all over, Gary fashioned a pine box in his own shop and, over the objections of county officials, buried his boy on Gardner land. In the wake of this tragedy, deep troughs of depression waged a back-and-forth battle with periods of manic energy for control of Gary’s mind.

In the days following the Joe Moore verdict, Gardner sat down at his computer and knocked off a quick letter to some of Tom Coleman’s victims. The Vigo Park farmer was particularly frustrated by the media frenzy surrounding the Tulia drug sting. The Amarillo paper’s interview with Tom Coleman was particularly troubling. “The statements given in his newspaper interview show him as almost too good to be true,” he told the recipients of his letter. “I have found that usually when something seems too good to be true, it is.”

For good measure, Gardner addressed a copy of his screed to District Judge Ed Self (who presided at most of the dozen-or-so trials connected with the sting), the Swisher County Attorney, District Attorney Terry McEachern, and a Texas Ranger or two. He then waddled across a vacant lot to the old grocery store that doubles as the Vigo Park Post Office, posted his incendiary missives, and waddled back to the house he had built with his own hands in most prosperous times.

“I mailed it, momma,” he told his wife, Darlene. “Now we’re goin’ on Defcon 1.” In the next few days, Gardner planted the long guns in his impressive collection by every door and window in his home. “I’m a paranoid son-of-a-bitch,” he explained.

My wife Nancy had a good reason for inviting Gary to our New Year’s Eve party. We had been doing some digging of our own and were just as skeptical of the big Tulia drug bust as he was. Charles Kiker, Nancy’s recently-retired father, had met Gary at the court house during Joe Moore’s trial. We were eager to get to know the only other white person in Swisher County who shared our concerns.

“I’m racist as hell, just like everybody else in this county,” he announced to the room. “I don’t gotta tell you folks,” he said, nodding in the direction of our Black guests. “You know how it is around here. I’m just warning the liberal preachers in the room.”

Then Gary continued his analysis of the situation. “It’s this damn pulpit-pounding sheriff we got. He’s too good for God and he’s using the law to run the niggers out of town and get back at me.”

Gardner glanced around to see if we were suitably shocked. We were. He grinned a devilish grin. Gary loved offending white liberals, especially if they were from New York City. Thelma Johnson, Joe Moore’s erstwhile girlfriend, and Freddie Brookins Senior, whose son, Freddie Jr. would soon go to trial, didn’t like Gary’s casual racism, but it didn’t surprise them in the least and, in the circumstances, they weren’t inclined to press the matter.

“I’m also a crazy sonofabitch,” Gardner continued. I ain’t joking either. I’m racist as hell, and I’m flat crazy. Before this is all over, you’ll know what I mean. Me being crazy is why we’re gonna win this deal.”

Gary, we soon came to realize, was bipolar, a fact that occasionally came in handy. Gardner had a low opinion of lawyers, so, when he decided Joe Moore needed to writ of habeas corpus he decided to write it himself. Gardner, I quickly realized, was a full-blown genius, but his dyslexia messed with his spelling and syntax while growing up in the Texas Panhandle messed with his grammar. In his manic phase, he’d stay up all night writing on Joe’s writ, then turn his copy over to me so Gardner the writer would sound like Gardner the talker.

“This thing’s a timebomb,” Gary assured me. “We ain’t just arguing the law; we’re changing the law. The crooked DA almost got away with his shit by exploiting loopholes in the legal code. So, I’m not just telling the Court of Appeals to bust Joe out; I’m tellin’ them to change the goddamn rules.”

Thanks to Gary, the writ we wrote for Joe Moore took conventional legal arguments to places a proper attorney would never dare to go. “Those judges gonna be shakin’ their heads at some of the horeshit we got in this deal,” Gary told me. “They gonna be sayin’, ‘you can’t say that—you can’t go there.’ But it don’t make a God damn. They ain’t gonna be able to set this sucker down. And when they get to the end they gonna say. ‘God damn! That big nigger got screwed!’”

Joe’s writ argued that the Coleman sting was a crude exercise in racial profiling. We noted that eighty percent of the forty-six defendants arrested in a single sweep were Black while every member of the remaining twenty percent was intimately related to the Black community. Black residents comprise only seven percent of the local population. Therefore, a reasonable person would conclude that the sting targeted the Black community. The onus was on the state to prove otherwise.

“Sometime in 1999,” we wrote, “there were more Black people indicted in Tulia than there were Black people eligible to sit on juries. The exclusion of black people from the judicial system was complete, utter, and intentional.”

By the time Joe Moore’s writ was complete, we were no longer fighting alone. Charles Kiker had written the Center for Constitutional Rights, William Moses Kunstler’s organization and the letter ended up in the hands of comedian-activist Randy Credico. In recent years, Randy has been in the news for running for mayor of the Big Apple and, yet more recently, for making Roger Stone so angry during the Wikileaks inquiry that the dirty trickster threatened to kill Randy’s cute little dog). In 2001, however, Credico ran the William Moses Kunstler Fund for Racial Justice and was looking for a good drug war narrative. The famed civil rights attorney was gone by this time, but Randy was close to the family. So, when he showed up in Tulia, he was accompanied by Kunstler’s daughters, Sarah and Emily.

The Kunstler sisters soon produced a documentary that made much the same arguments Gardner and I were making in Joe Moore’s writ. The documentary attracted the attention of Vanita Gupta, then an intern with the Legal Defense Fund in Manhattan. Ms. Gupta is now the Associate Attorney General of these United States; back then she was a recent law school graduate. Using what we called “the Kunstler video” as bait, Gupta lined up some of the most prestigious law firms in the nation to represent the Tulia defendants.

One day, Vanita Gupta and Gary showed up at my door. “Where’s that damn writ?” Gary asked, “I’m turning it over to this pretty little lady. Those bigshot lawyers back east won’t know what to make of it, but it’ll tell them everything they need to know about this deal.” I fetched the latest iteration of our 300-page document and placed it in Vanita’s hands. I experienced a great rush of relief. Part of me was convinced that no one in Austin would ever read our cartoonish creation.

It wasn’t easy for Gary to relinquish a piece of work he had worked on around the clock for months. Control was important to Gary. Controlling the action, controlling the story, and, in particular, controlling his adversaries. He wouldn’t have surrendered the writ to just any attorney. That he let Vanita have it testifies to the confidence she had earned among us.

In the months that followed, we organized repeated trips to Austin to lobby the legislature. Once we rented a bus and took 46 Tulians to Austin. After years of carrying his massive frame, Gary’s knees were beginning to give out, and he often had to use a wheelchair to get around. But nobody was going to stop him.

When we entered an office, Gardner was always the lead off hitter. His role was to convince conservative legislators that salt-of-the-earth Texans were upset about what happened in Tulia. “I just want you to know that I’m the most conservative, redneck-farmer, law-and-order, straight-ticket-Republican in Swisher County”, he would tell the earnest young staffers we encountered. “I’m a founding member of the County Crime Stoppers and, when I was younger, I was a traffic cop. I believe in the law. I love the law.”

“I was a Baptist minister for twenty years before I moved to Swisher County,” I would interject. “When I read that people were convicted on the uncorroborated word of a shifty character like Tom Coleman, I just had to speak up. The law of Moses, the teaching of Jesus and the Apostle Paul all agree: no one should be convicted on the uncorroborated word of a single witness.”

“My husband and I have three drug sting orphans living in our home,” my wife, Nancy, would add. “And every evening when we tell those sweet children a bedtime story and kiss them goodnight, it just breaks my heart to hear them ask when their momma is going to get out of prison.”

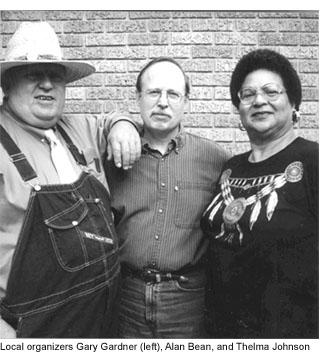

Then we’d have Sammie Barrow, Freddie Brookins, Mattie White or Thelma Johnson talk about their family and friends who had been unjustly convicted in the operation.

And when we were done, jaws were hanging open in disbelief.

Eventually, to the great dismay of the locals, righteousness prevailed in Tulia and Gary was featured in major media outlets across the nation and around the world. Frankly, most of his allies were afraid he wouldn’t live to see justice done. But he did. In fact, he lived another eighteen years. But now he’s gone. And nobody knows. I’m writing this to give Gary his due. He is undoubtedly the most complicated, relentlessly unique, individual I have ever known.

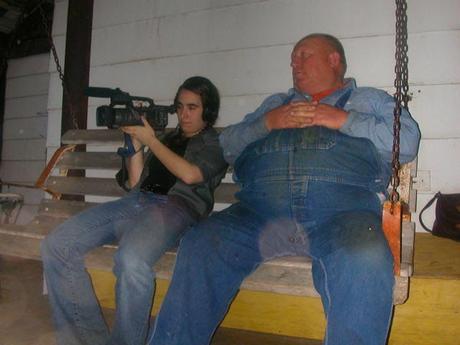

A few months after twelve wrongfully convicted Tulians were released in a dramatic proceeding at the Swisher County Courthouse, I wrote a song about Gary. He was having a hard time coming down off the drama. “There’s a reason the media loves me,” he once said, “I’m a cartoon. I’m ridiculous. I know it. But everybody loves a cartoon. I’m the racist redneck standing up for his Black friends. What a story!”

I called my song, “Cartoon Man” and I dedicate it to Gary’s memory:

My daddy’s ghost still comes around,

Climbs in my pickup truck and eases into town.

It takes a lot of lost and found

To make a Cartoon Man.

You can’t console me, nobody understands.

You can’t control me, I’m the Cartoon Man.

Best crazy act you’ll ever see,

On Sixty Minutes or in People magazine,

Perched on a porch swing with my hound,

I’m the Cartoon Man.

You can’t console me, nobody understands.

You can’t control me, I’m the Cartoon Man

Had me two good crop dusting planes,

Until old Charlie took the cancer in his brain,

I’ll never see that kid again,

I’m the Cartoon Man.

My daddy’s ghost still comes around.

Climbs in my pickup truck and eases into town.

It takes a lot of lost and found

To make a Cartoon Man.