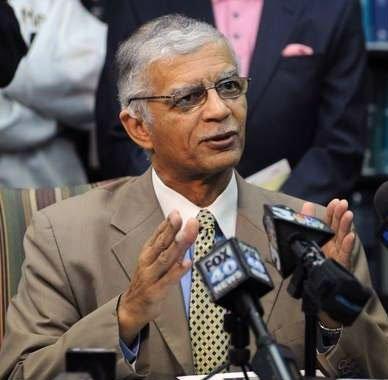

Chokwe Lumumba

By Alan Bean

I didn’t know much about Chokwe Lumumba when I called him up five years ago. I gathered from his name that he was a Black nationalist. All I really knew was that he had served as defense counsel for Curtis Flowers, a man who has now stood trial an unprecedented three times for a crime he did not commit. I didn’t realize I was speaking to the future mayor of Jackson, Mississippi.

Lumumba died recently after serving only eight months in office, apparently of natural causes.

From reading the voluminous trial transcript of Curtis Flowers’ second trial, I knew Chokwe Lumumba was a passionate defender who took his work very seriously. In defending Mr. Flowers, he had crisscrossed the state, interviewing potential witnesses and re-interviewing the state’s hapless witnesses.

If anything, Chokwe appeared to be too invested in the case. As the trial drew to its close, Lumumba told the all-white jury that racial bias was blinding them to the obvious. When I read that rebuke I found myself wishing that he had kept his opinions to himself.

But Chokwe knew he could not vindicate his client at trial. Not in Gulfport, Mississippi. Not that day. All he could do was firm up the record so the appeals court could give his man a second chance. In that case, making direct reference to racial bias was a good plan. The inevitable guilty verdict was eventually reversed on the grounds of racial bias in jury selection.

Chockwe Lumumba was part of the second wave of civil rights activists who no longer saw full integration as realistic or even desirable. They spoke of creating a separate country, comprised largely of “Black Belt” counties in the South, where Black people could chart their own course free from the debilitating influence of White bigotry and racial resentment.

It is ironic, therefore, that a dedicated Black nationalist ended up as mayor of Jackson, Mississippi, a city that was once at the very heart of the never-in-a-thousand-years struggle for White supremacy.

But those who feared that Lumumba would serve only his Black constituents were soon proved wrong. William Winter, one of the few progressive politicians to serve Mississippi as governor, spoke at the funeral.

“Based on the stereotypes this old white man had formed about (Lumumba), I thought that he would divide our city. I was wrong. The strong leadership of Chokwe Lumumba has opened the door to a bright future for us.”

Rest in peace, Chockwe Lumumba.

Speakers at Chokwe Lumumba’s funeral include Myrlie Evers-Williams, former Gov. William Winter

JACKSON, Mississippi — Hundreds of mourners filled the Jackson Convention Complex on Saturday for Jackson Mayor Chokwe Lumumba’s funeral, which lasted nearly five hours and included tributes by Myrlie Evers-Williams, widow of civil rights leader Medgar Evers, and former Mississippi Gov. William Winter.

Myrlie Evers-Williams remembered Lumumba as someone who pushed federal prosecutors to try the man who killed her husband, bringing about the conviction of Byron de la Beckwith.

“The slogan ‘One City, One Aim, One Destiny’ must be continued in the spirit our beloved mayor started,” she said.

The 66-year-old mayor, born in Detroit as Edwin Taliaferro, died Feb. 25 after eight months in office. The Hinds County coroner said he died of natural causes.

Lumumba’s daughter and youngest son, Rukia Lumumba and Chokwe Antar Lumumba, also spoke.

Chokwe Antar Lumumba said his father’s love freed the Scott sisters — women who had been given life sentence for an $11 robbery. As an attorney, Chokwe Lumumba won a clemency order in 2011 from Haley Barbour, then governor.

“Love changed Jackson, Mississippi. And Chokwe Lumumba was love,” he said.

Winter, 91, told the mourners, “Please excuse this stereotype of an old white man,” because he had been afraid before Lumumba’s election that he would divide the city. “I could not have been more wrong,” Winter said.

He said Lumumba “brought a spirit of inclusiveness and reconciliation that are essential to solve our problems.”

“The finest memorial that we can erect to him will be the creation of a community here in Jackson … where every person … can be assured of being treated with dignity and respect,” Winter said.

Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan sent representatives and a letter.

The funeral included an “eight-bowl ceremony” which opened with a bit of wine was poured out for each person a speaker described as important in Lumumba’s life. Seven other people then spoke of memories symbolized by honey, for the sweetness and goodness of life; lime, for bitterness and hurt overcome; salt, for wisdom, balance, and moral choices; cayenne pepper, for recovery from crisis; water, for spiritual depth and renewal; palm oil, for community and family power; and coconut, for blessings.

There were gospel hymns, African drummers, and a performance by a dancer and two costumed stilt-walkers. The drummers played as Lumumba’s family walked out of the auditorium behind the casket.

Acting Mayor Charles Tillman, who will serve at least until a special election April 8, said, “Yes, of course we know there must come new leadership. But like you, we have dreams and hopes that whoever comes will have similar vision and keep the momentum going.”